Christine Sun Kim’s work leaves little room for misinterpretation. Clarity, for Kim, is a reality of survival. “American Sigh Language,” the artist’s recent solo exhibition at François Ghebaly, makes it clear: for Kim and other Deaf individuals, intelligibility serves as a kind of armor against discrimination. Being misunderstood isn’t just inconvenient; it can mean lost opportunities, even the loss of her rights.

The night before I visited the exhibition (and met Kim, who offered to meet and speak to me about the work), I fell into a YouTube rabbit hole, watching as many of her interviews as I could. Among them were her 2020 Super Bowl performance, early Whitney Signs educational videos, and her now-viral 2015 TED Talk, where she frames her art practice as a reclaiming of sound, interpreting American Sign Language (ASL) through a musical lens. In the talk, she fans her fingers out, assigning one ASL grammatical parameter to each: facial expression—pinky, body movement—ring, and hand shape—middle. Pressing each finger down independently like a piano key, she demonstrates how English is a linear language. Then, slamming all fingers down at once to form a chord, she shows how ASL communicates meaning holistically, through simultaneous, embodied gestures. The next day at François Ghebaly, Kim (joined by her interpreter, Beth Staehle) explained that the exhibition’s title, “American Sigh Language,” originated from a typo that mistook “Sign” for “Sigh.” This slippage became a conceptual anchor, gesturing toward the invisible labor of navigating a world where the burden of comprehension falls disproportionately on disabled people, especially disabled artists of color.

In the first room, the collective sighs of sixty-six Deaf individuals reverberated through the space, spanning a spectrum of emotion: frustration, grief, relief. For the ten-channel sound piece Community Sigh, Kim invited Deaf colleagues from around the world to submit 30-second voice recordings, capturing shared experiences of Deafness. The audio was grouped and pressed onto five clear vinyl records, which spin on a loop in the gallery. Their transparency evokes breath and the intangible in-between. Record weights, modeled after abstract ASL hand shapes developed with MIT Media Lab, sit atop each vinyl, both physical stabilizers and metaphorical burdens.

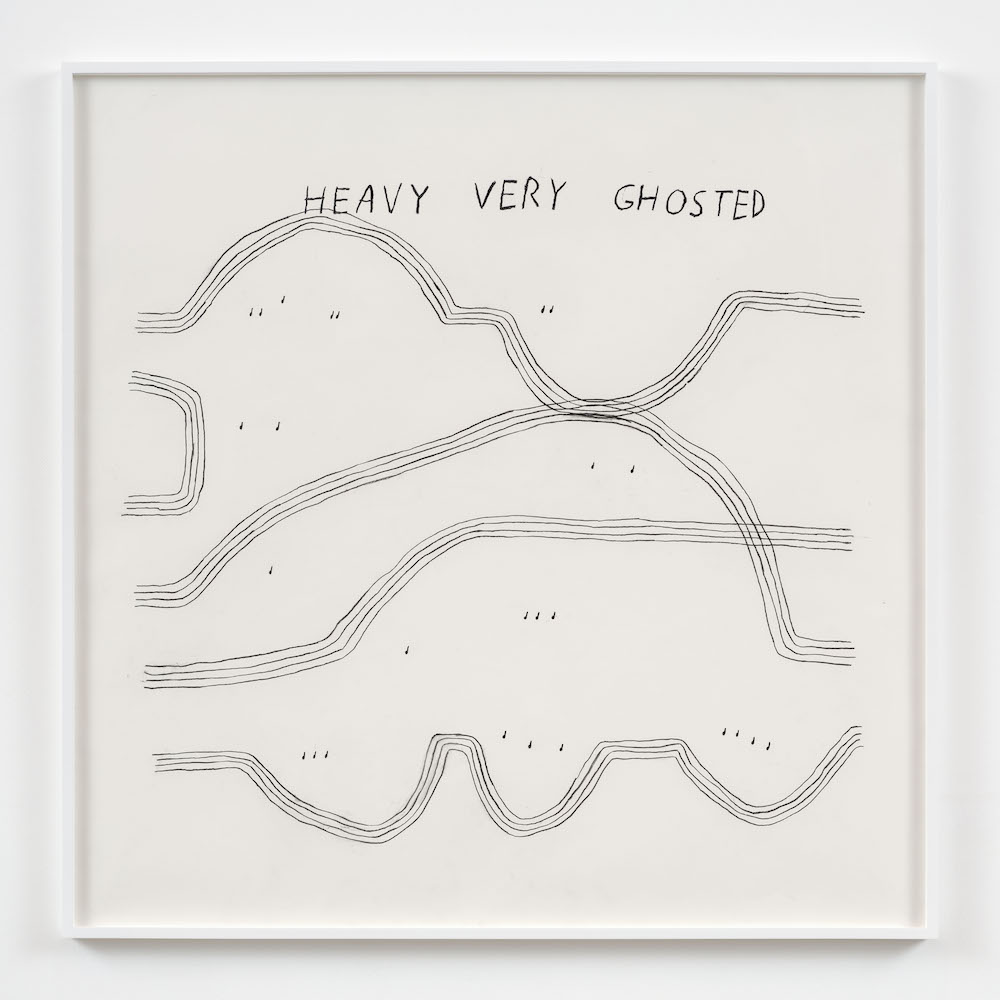

Christine Sun Kim, Heavy Very Ghosted, 2024. Photo: Paul Salveson. Courtesy of the Artist and François Ghebaly, Los Angeles, New York.

As Kim walked me through the works, she used her body to demonstrate the stylistic choices behind various ASL phrases, emphasizing that phrasing must feel natural. In the next room, she introduced her well-known charcoal drawings, which explore themes of educational exclusion, socialization discrepancies, and her shifting relevance within the mainstream art world. Standing before Heavy Relevance (2024), she explained how a musical staff is traditionally signed with five fingers drawn across the body. But in her drawings, she uses only four lines, leaving out the thumb, because signing with it extended feels unnatural. Rendered in black-and-white and paired with declarative text, her charcoal drawings assign meaning with precision. Every question has a clear, considered response.

But this precision can also feel overly didactic, clinical even. And perhaps, in a world so unfriendly to political and personal nuance, this didacticism is necessary. But the charcoal drawings often feel more like carefully constructed answers than open invitations for interpretation by informed viewers. It’s worth considering if the work could offer more space for complexity without sacrificing its politics.

Installation views, Christine Sun Kim, “American Sigh Language,” François Ghebaly Gallery, Los Angeles, 2025. Photo: Paul Salveson. Courtesy of the Artist and François Ghebaly, Los Angeles, New York.

In Community Sigh, Kim engages the viewer on less fixed terms. The voice, so often marginalized within Deaf experience, is placed front and center. The sounds resist legibility, translation, and transcription. The breath simply exists, immediate and unmediated, without the scaffolding of interpretation for the viewer’s comprehension. It’s the only part of the exhibition that relinquishes control over its reception. Because it risks ambiguity and emotional vulnerability, Community Sigh is the most resonant work in the show.

In the days after visiting, I wondered: What would Kim’s work look like if she weren’t tasked with being understood? If she could create work solely for Deaf audiences? What would accessibility look like then, not as something offered to the able-bodied, but required from them?

Another identity marker that remains quietly sidelined is Kim’s Korean American background. In a New York Times profile by Aruna D’Souza, Kim shared that her parents didn’t teach her Korean because a white speech therapist told them it would confuse her. That decision, made in the name of assimilation, echoes another kind of loss. Cultural erosion, like clarity, becomes a form of self-defense. In this light, legibility is never neutral. It’s always a negotiation of power, whether shaped by race, ability, or language.

“American Sigh Language” is unapologetic in its exhaustion. It doesn’t contort itself for viewer comfort. Instead, it exposes the labor required to be understood. Though the show left me with more answers than questions, I found myself wondering: What would it mean for this work, and for Kim herself, to be allowed opacity? To sigh, and not explain why?