From 1973 to 1985, Chris Killip lived among and photographed working-class and underclass communities in the north of England whose livelihoods depended on traditional heavy industry. His subjects include the declining coal mining and shipbuilding cities of Tyneside, a contingent of sea-coal gatherers in Northumberland, and others eking out a precarious living on the economic margins. Shooting in black and white with a large-format camera, Killip produced a devastating record of the de-industrialization of the region. “Candid” is profoundly inadequate to describe this series of wrenching, tender photos, of which several portraits are among the most memorable.

A selection, titled “In Flagrante,” was published in 1988 by Secker & Warburg. The series has been shown widely in Europe, but never before exhibited in its entirety in this country, even though Killip, Manx by birth, who lives in the U.S., continues to publish, and has taught at Harvard since 1991. Slightly revised, “In Flagrante Two” includes three new prints, bringing the complete set to 50. This work is remarkable for its emotive power, technical brilliance and continuing social relevance. Additionally, Steidl’s publication last year of a new version of the book, also titled In Flagrante Two, raises familiar but unresolved questions about artists’ intentions in relation to the critical reception and interpretation of their work.

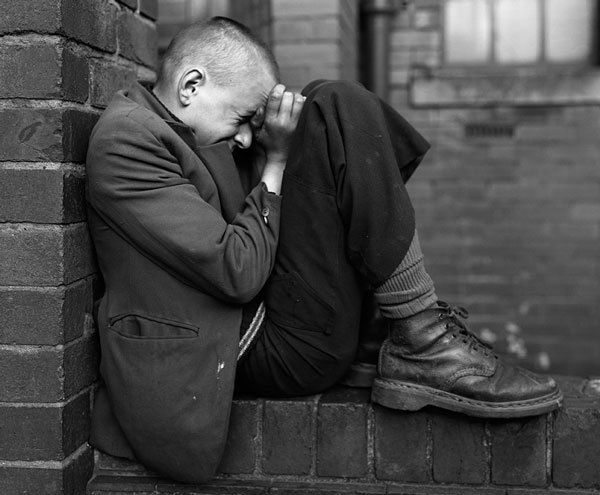

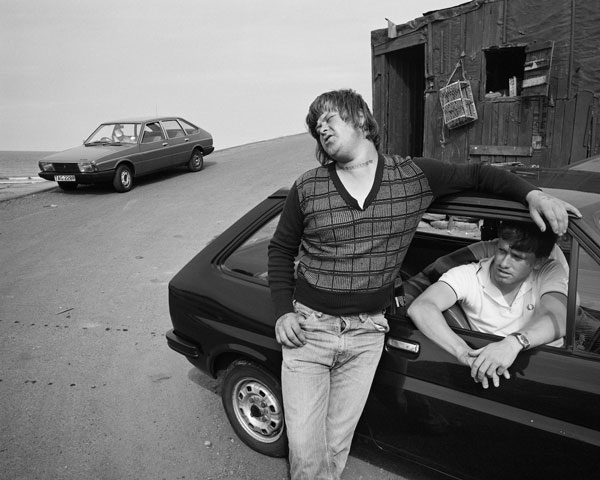

The exhibition was tightly hung, underscoring the economic constraint, even suffocation that the images depict. They are silver gelatin prints, 20x 24 inches (or the reverse), in an open edition. Anxiety is nearly unremitting. Clusters of glassy-eyed young men sniff glue on a beach and slam dance in a crowded club. The hulking hull of the Tyne Pride looms at the bottom of a vacant street. A group of striking miners and their families mill about, outfitted with signs, umbrellas, provisions, and a pig mask. Occasionally the edge softens—a dad gives his son a peck; somebody plays with a puppy. The leading chronicler of the American face of the Great Depression, Walker Evans, is a major influence. Killip’s eye is a bit more romantic but just as sharp, and his knack for composition is equally impressive. Crabs and People, Skinningrove, N Yorkshire (1981) is about pictorial space as much as economic subsistence.

And just as the grinding poverty Evans documented persists, the grim realities in Killip’s work still resonate. As London and the southeast dominate the U.K. economy, much of the north has not recovered from de-industrialization, and its infrastructure continues to crumble. Recently, the government initiated a “northern powerhouse” program to address this disparity by decentralizing authority over spending, but many commentators think it at odds with Whitehall’s austerity measures. The problem likely will not be solved any time soon.

Chris Killip, From the series “In Flagrante Two,”Bever, Skinningrove, N Yorkshire, 1980, © Chris Killip, courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

No doubt many Americans became aware of Killip via Errata Editions’ extremely useful “Books on Books” series of compact facsimiles, of which In Flagrante was among the first to be published, in 2008. That volume prompted Killip to plan the new version. Advances in technology allow In Flagrante Two to replicate closely his stunning prints, each of which is allotted a full page, not run across the gutter. Location titles are newly listed.

While his focus is clearly the human cost of busting the unions concurrently with dismantling the welfare state, Killip has called it “simplistic” to read the work principally as criticism of Margaret Thatcher’s monetarist policies and related actions, as many have done. In an attempt to correct this perception, the new book’s preface lists the names, party affiliations, and years in office of the four Prime Ministers—Heath, Wilson, Callaghan and Thatcher—who presided over the British economy during the relevant period.

The exhibition’s installation and the photos themselves provide further clues that, for Killip, photography is about image making—not ideology, but storytelling. Bracketing the sequence are two photos of the same subject: a destitute woman in a filthy coat, her face obscured by a shawl, slumped and out cold in a bus shelter. The shadow of the photographer and his gear, seen in profile, falls across her. The point might be that the camera deals with the factuality of people and their circumstances, not cause-and-effect relationships. A prominent wall text relates a brief anecdote that concludes with the protagonist insisting, “I don’t know nothing about no f…ing history, I’m just telling you what happened.”