THAT WAS THEN THIS IS NOW. Ed Ruscha’s lithograph and the banner image for his 40-year survey at Gagosian Madison Avenue says it all: it was a different art world when Ruscha arrived in Los Angeles in 1956. Now, he’s blue chip and according to my editor, a celebrity—the inverse to the James Franco phenomenon. We’re shuffling through the names of various uber-successful artists, attempting to sort out the vagaries of art world celebrity and success. While I toss out other names, she keeps coming back to Ruscha.

“Didn’t he hang out with one of the Chili Peppers in that Pacific Standard Time video?” she remarks.

Then, after several more names, I hit a nerve: “Well, how did Murakami get to be such a hot-shot?” she wonders.

“Hell if I know,” I venture. I recall wandering through the artist’s mid-career retrospective at MOCA a few years back, feeling there was something painfully banal about the work. Worse, still, was the Louis Vuitton boutique dead center of the exhibition, which seemed to say, “It’s all about product.”

We skirmish over more names—Hirst, Koons, Emin—and the metrics we’re using, but the questions remain: How does one measure success in the art world? What is the relationship between the sale or auction price of a work of art and its value? In a world where bankable brands are currency, does commerce pollute the intellectual and aesthetic integrity of the work?

More than one artist has seen their brand unravel after messing with the formula or daring to assert aesthetic promiscuity. Demand is based on subjective criteria and fueled by the need for conspicuous consumption. And capital in search of extraordinary returns feeds runaway speculation, which in turn, is pumped up by super-dealers like Gagosian and Zwirner, super-collectors like Saatchi and a whole coterie of others who wish to exploit the churn of the market. Like catching lightning in a bottle, it is unpredictable and the potential for windfall prompts questions of market manipulations. Rather than hedge funds, the art market is the last wild-west.

For the moment, let’s separate out the power, money and market position from aesthetics and idealism. The art world—or at least a segment of it, along with other intellectually esoteric enterprises—prides itself on going in for obscure cultural luminaries, not pop culture stars or reality TV personalities. Celebrity carries the taint of vulgarity. You might say our aspirations are to be well known, but not too well known. Embedded within this reverse snobbishness is a kind of self-delusion—that the reverence of the cognoscenti does not constitute a celebrity culture. We think it is at least in part predicated on achievement or high culture rather than mere popularity, that it’s qualitatively different from what the Frankfurt School dismissed as mass culture.

And the most visible sign of success, aside from money, is for an artist to ascend to pop-culture notoriety. Hypothetically, let’s say someone writes a rock song about you. Think of the Modern Lovers song, “Pablo Picasso.” It reached an even bigger audience when the Burning Sensations covered it for the LA cult movie Repo Man. But “Pablo Picasso” is not just any song. The refrain—“He could walk down your street; girls could not resist his stare. And so, Pablo Picasso was never called an asshole—not like you!”—reinforces the artist’s mystique.

Then there’s Bowie’s “Andy Warhol”—the other celebrity. Warhol’s mystique was assuredly different than Picasso’s. He was a celebrity for a number of reasons, not least because he sought out celebrity, inviting all manner of the rich and famous to the Factory, making icons of their images alongside icons of prosaic objects.

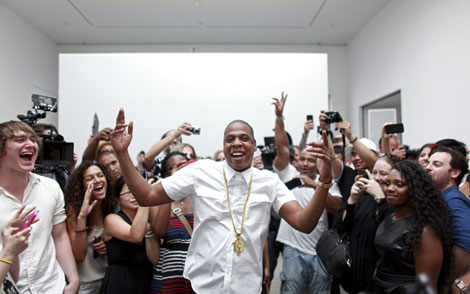

Now there’s Jay Z’s “Picasso Baby,” and if there was any doubt about celebrity culture in the art world, all one needs to do is watch Marina Abramovic vamping with Jay Z at Pace Gallery last summer to know what’s up. “Picasso Baby” is not entirely ironic, reminding us that making, buying and selling art is a way to transcend social class. It is also a clever commentary on the international art fair and auction circuit. And it reminds us that as lofty as one might get about art, it can simply be reduced to owning something. It’s a powerful aphrodisiac. As Jay Z says, “Go ahead lean on that shit…you own it.”

It should be no surprise then, that many people find work by art stars leaves them cold. Since when do we view Jeff Koons’ balloon dogs as anything other than shiny baubles? Nor should it astonish that the art world’s larger-than-life personalities don’t loom as large in the public’s imagination as rock stars: the art world is perilously self-referential and arcane. Even among the cognoscenti, toss out a name—Richter, Cattelan, Barney—and you might get a 30-percent response.

The dark side of celebrity—infamy, of the type William S. Burroughs is noted for, for shooting his wife in Mexico, allegedly in a game of William Tell gone awry, or Carl Andre, who was acquitted on a murder charge in connection with the death of his first wife, Ana Mendieta—holds a special allure in the popular mythology of the art world. The black comedy/satire Art School Confidential delivers a tart send up of the cynical and pervasive art world myth that such notoriety can ignite one’s career, much like dying can send the value of an artist’s work through the roof. When the film’s protagonist falsely claims credit for the work of a serial killer/artist who has been painting disturbing portraits of the corpses, he perversely achieves art star status.

Salacious gossip titillates, and pushing at boundaries may generate short-term attention but it also distracts. Money and the power that comes with it add a pedigree based on scarcity. The farther one ascends up the ladder of art world success, the higher the stakes. And it is not simply a matter of artists being turned into commodities—though an argument can be made for that. Many of those artists—in fact, I would venture to say all those who climb that ladder—are interested in the result: developing a successful brand that has staying power. Sure, this vastly oversimplifies the story and leaves out artists who purposefully develop a heterogeneous practice, fully aware of the ramifications.

The notion of celebrity is strange and shifting territory—at times, ambiguously defined—but one of the things that is useful is our ability to abstract celebrities and think of them as other. It is easy enough to view them as icons whose strengths and successes we covet. And within that murky calculus—the exchange between the icon and the adoring public—the manufacture of desire meets the point of sale.