While contemporary Chinese artists such as Ai Weiwei and Cai Guo-Qiang often grab international headlines with their projects and exhibitions, there are very few women among them. Lin Tianmiao is one of the few. That is very much due to the strength of her work, the power of its imagery, which is at once bold and delicate, and of its message, which is female-centric if not what she would call Feminist.It is also at least partly due to the fact that she lived in the United States for eight years, so she had a chance to absorb the language of conceptual and installation art, and where I think she must have seen that the body itself was a valid subject for artwork. Thus, we (in the West) find her work easy to “read.”

Lin is noted for her focus on using sewing and embroidery, textiles and domestic objects—techniques and materials generally associated with “women’s work,” techniques and materials the pioneers of Feminist Art in the United States featured in their work, although Lin herself doesn’t care for the “F” word. This is due, I think, to her misreading of Feminism as a fait accompli. In an interview with writer and educator Luise Guest, she actually said, “I don’t think there is any feminism in China. Mao said that women hold up half the sky, but we have not reached that level.”

But in fact her work is feminist in the sense that it acknowledges and valorizes women’s work and place in society. One of her best-known series utilizes a technique she calls “thread winding,” enveloping objects with cotton or silk thread wound around and around them. This laborious process reiterates the meticulous and endless, often thankless, work women have traditionally done for the home. “Nowadays life is so complex we don’t even know how to sew buttons,” Lin said in the Guest interview, “so working with fabrics is a return to a simpler past.” At the same time, she’s created an aestheticized object for our admiration, an object no longer able to serve its original function.

Born in 1961 in Taiyuan in Shanxi province, Lin grew up in a culturally inspired household. Her father was a painter and master calligrapher, and her mother taught traditional dance. In 1984 Lin received a BFA from Capital Normal University in Beijing. Four years later she and her husband Wang Gongxin, a video aritst, moved to the United States and lived in the New York area, like a number of their fellow Chinese expat artists. Lin worked in textile design, and didn’t really launch her art career until she returned to Beijing in 1995. Deep childhood memories of helping her mother sew clothes for the family launched her on the technique of “thread winding.” Since then Lin has often been included in major exhibitions of contemporary Chinese art.

In 2012 the artist enjoyed her first American retrospective at the Asia Society in New York, “Bound Unbound: Lin Tianmiao,” and the next year her first West Coast museum exposure at the 2013 California-Pacific Triennial at the Orange County Museum of Art. The retrospective featured all her major bodies of work to date, including her magnum opus “Bound and Unbound” (1997), where she thread-wound some 800 domestic objects, strewn across the floor, before a screen showing strands of hanging threads being cut by an old-fashioned pair of scissors. The objects included utensils, bowls, bottles, even furniture—one of which was a table-mounted sewing machine.

The title of the work and its visual manifestation also brought to my mind notions of women’s condition as domestic servitude, as well as suggesting bound feet and bound existences in patriarchal Chinese society. Lin does not work in a vacuum—she openly admits she has teams of women help her in making her work, and she pays them a fair wage.

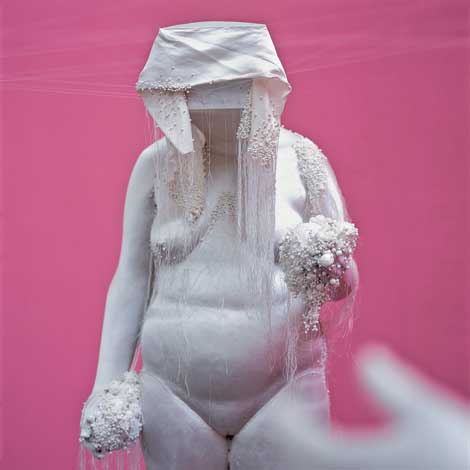

The exhibition also showed how she has used her own body in digitally altered photographs, and in the life-sized sculpture Chatting (2004). In the latter, six figures, presumably based on her own Rubensesque form, stand facing inward in a circle. Their faces are flat rectangular surfaces, and their heads are connected by threads. The accompanying audio is of women talking, laughing, weeping—suggesting the intimacy of conversation women may share with one another.

The emphasis on the individual human body is actually quite revolutionary in Chinese art. For centuries, the literati, heavily influenced by Taoism and Zen Buddhism, emphasized a kind of disembodiment, of dematerialization—it reflected a philosophical rejection of the physical world, of material things. Of course, Lin is not the only contemporary Chinese artist to find expression in the body. Zhang Huan, based in Shanghai and New York, focused on body art for several years. He famously painted his face black with Chinese characters, done over and on top of each other, and in “12 Square Meters” he sat in a fly-infested toilet for an hour, while naked and covered in honey. Lin uses her body more in representation, rather than live performance, and in less masochistic ways.

OCMA showed one of her most celebrated pieces, “All the Same” (2011), an installation which incorporates 180 bones (out of 206) in the human body. Each piece is wound in a colorful silk thread, with the end of the thread falling to the floor below—starting with a reddish hue and ending with the green/blue shades. They present a rainbow of colors that celebrates human mortality, and are hung on the wall the largest to the smallest in succession. (Although, for visual balance, the two femurs are hung on either side of the skull. Also, I note in the description that these are “synthetic bones”— in case anyone gets creeped out by real bones.) My issue with the OCMA installation, which I saw, was that the wrapped bones were hung high, well above eye level, and thus harder to see, whereas I’ve seen in video another installation where the bones were hung about eye level.

A recent show at her New York gallery, Galerie Lelong, was of her series “Badges”—a rather witty installation of embroidered cloths still in their embroidery hoops, hung in midair. In each hoop was a word in English letters or Chinese characters, derogatory words which are often throw at women—“slut,” “floozy,” “broad.” While I’m not sure the display was that successful, I found that “Badges” reflected a lively sense of humor, which I hope Lin will continue to explore to future undertakings.