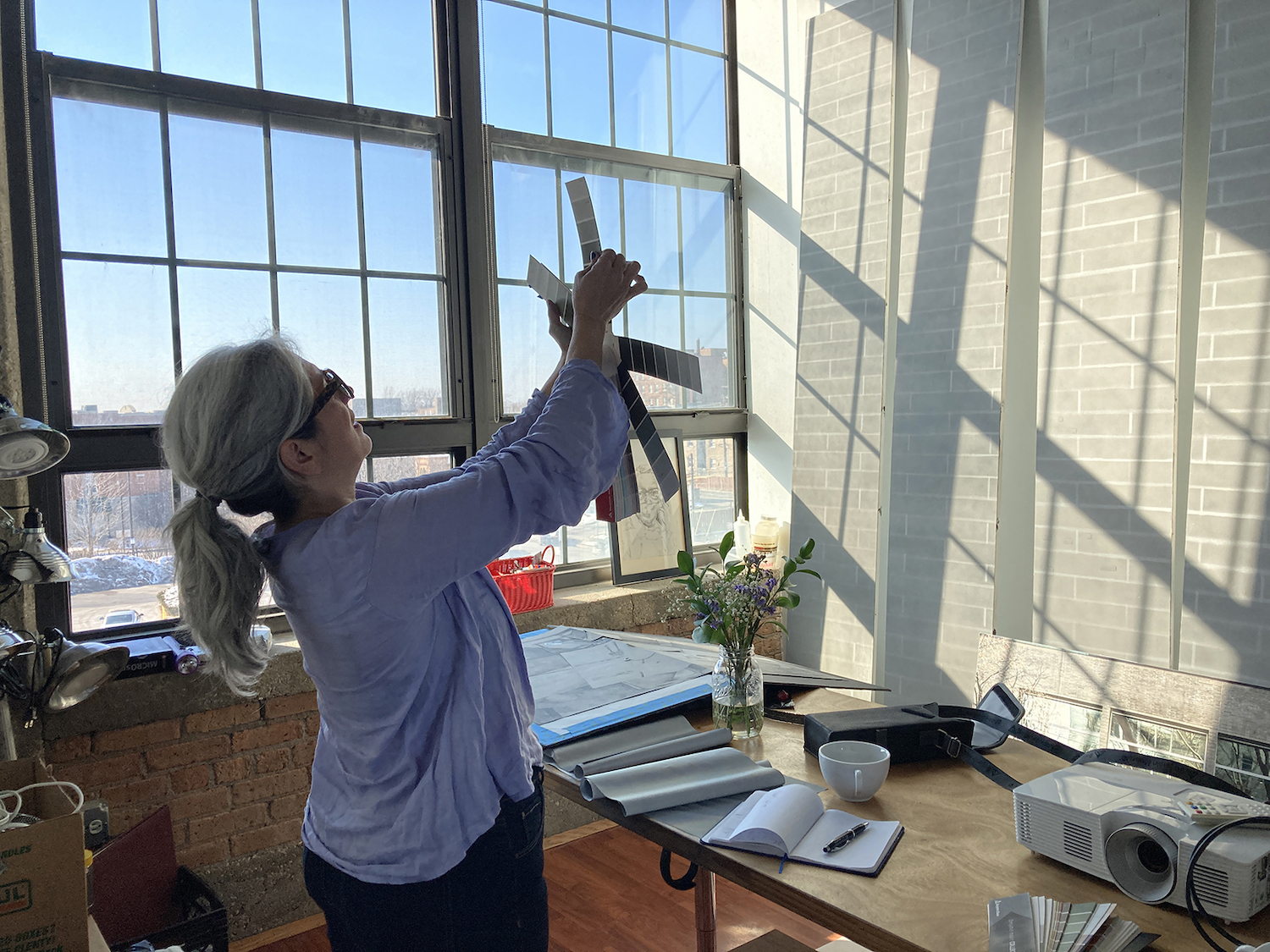

It is 3:02 p.m. on February 26, and we are looking intently at the north wall of Paola Cabal’s studio while the Midwestern afternoon light streams in through her unobstructed west windows. Cabal is rapidly leafing through a Benjamin Moore paint-chip book, holding the color chips up to a patch of sunlight on her wall to identify the color she might use to replicate the light.

“There it is: 212570.”

Cabal is describing the process by which she creates installations that document the light in a space. Her process is exacting in the extreme. She “maps” the effects of the light within the given space at a specific time on a particular day and then painstakingly re-paints the walls—and sometimes the floor—to recreate the lights and shadows from a past moment. The effect is at once subtle and transformative.

Cabal at work.

“You could miss it,” Cabal acknowledges, and people sometimes do overlook her interventions. The subtlety and familiarity of sunlight striking a wall is easily taken for granted. But once you’ve observed the discrepancy—say it’s 7 p.m. and the light on the wall is from 3 p.m.—something magical happens. You’re experiencing two moments in time at once. It’s disarmingly simple, but it startles one into paying closer attention to every detail of a space, as if it might reveal something new, something that was missed earlier.

As we talk over the course of several hours, the light moves across Cabal’s studio wall. Leaning against it are eight panels, each 15 1/2 inches wide by 9’4 inches tall, on which Cabal has painted the running bond pattern of a brick wall. These were part of her recent installation, “What Means Light,” at the Arts Club of Chicago, and they reference the venue’s western exterior wall. The panels are made of gray retro-reflective fabric, and the lines indicating the mortar are coyly painted in matching gray paint.

As my angle of vision shifts, the figure/ground relationship switches from dark-on-light to light-on-dark, and in some places the bricks vanish altogether, reappearing when I move my head. It’s mesmerizing, like looking into a trick mirror, and the disappearing is as suggestive as the appearing. In the actual installation, each panel was one side of a four-sided tower, and the eight towers stood within the fenced garden of The Arts Club.

What Means Light, 2020–21, site-specific installation at the Arts Club of Chicago. Photo by the artist.

When I visited the installation in situ in November 2020 (it remained on view until late May 2021), I was unable to see these panels, because they faced toward The Arts Club and were visible only from the inside of the building, which was closed during much of the pandemic. The panels I saw from the street, looking through the wrought-iron fence at the corner of St. Clair and Ontario Street, were alternately composed of illuminated light-box photos of views across the avenue (as seen from inside the club’s members-only drawing room) and painted images of the brick wall as seen from the sidewalk. Each panel reproduced the light at a different time of day on the spring equinox, and there was an uncanny sense that I was being admitted to a view that was simultaneously accessible and out of my reach. From one point of view, the painted sides depicting the wall would line up with my view of the wall itself and nearly disappear. But when I turned around to compare the view across the street with the view depicted in the light boxes, I couldn’t see both at the same time and had to rely on memory: appearing and disappearing were built into the body’s relationship to the space.

Back in the studio, Cabal takes out a spectacular drawing depicting coffee cups, napkins and silverware on a table in what looks like a diner. It is a proposal-drawing for an as-yet-unrealized project called “The Everland Café,” an immersive installation in a functioning coffee shop where everything—the cups, the tablecloths, the chairs—carries and casts shadows as if illuminated by sunlight entering the windows at 10:30 a.m. It is, perhaps, as impossible a project as it is understated: a place where forks, chairs and saucers move but their shadows stay put. This, Cabal admits, is one piece that she would like to create as a permanent installation, and she laughs as she imagines setting magnets in the tables to rotate the cups into their “proper” orientation relative to their shadows as soon as customers set them down after a sip.

What Means Light, 2020-21, site-specific installation at the Arts Club of Chicago. Photo by Michael Tropea.

Although Cabal initially studied figurative painting (and she makes exquisite drawings), her work is typically ephemeral and doesn’t usually result in a permanent art object. I note that in her studio we are looking at proposals for future projects and artifacts of past ones, but the works of art themselves are not there. “Non-portable experiences” is Cabal’s description of her work. This emphasis on the impermanence of experience is at the core of her practice. If the standard modus operandi of representational painting and drawing is to make that which we value appear permanent, Cabal’s practice is a kind of reversal in which the ephemeral is arrested temporarily but always about to vanish. As she says: “It forces you to pay attention to the present in a way that a legacy object doesn’t.”

However, there is also a way in which her work is entirely made possible by drawing. There is a slow, deliberate quality of attention in her work—a disciplined practice of observation—that one finds in great drawings, and she uses this to give physical form to the act of paying attention. But Cabal is quick to note that she uses drawing as a means to an end, as a kind of primary research. Rather than depicting something known and stable, it is a way to find out something that she didn’t already know when she started. “These are the dividends of slow,” she tells me. “That’s the work of attention.”