To write about Charlotte Schulz’ drawings requires a language equal to their elegant and surreal lyricism. The poet Jorie Graham comes close, describing a mythical space as consisting of “little whelps, vanquishings, discoveries, here under this / rock / no, over here, inside this sky, or is it below? / and everything now trying to arrive on time / ten thousand invisible things all.” Schulz’ large-scale charcoal sketches on paper are so exquisitely rendered that from across the room they radiate attentiveness. One could meditate alone on her deft handiwork, thick with details; for example, an interior scene’s sofa cushions decorated with smaller editions of narratives in the larger vignettes.

However, the work is perplexing. Scenes depicted follow the rules of perspectival imagery but not other expected visual logic. In The impossibility of keeping borders: a succession of becoming-times balances on the strata of an unrecoverable event. (2011) billowing ash-gray and black smoke fulminates overhead with a string of lit hanging lamps seemingly tethered to the smoke. Beneath is a building, or buildings, with semi-transparent walls. The structure’s roof has collapsed on the left, leaving a ruction of broken beams, next to which a solitary penguin faces away from the viewer. Seemingly close to the penguin, on the other side of the almost-wall, is an interior comprised of a leisurely sofa, and (outside?) more spilled, fragmented wood, but also (inside?) a line of standing telephone poles with connecting wires intact. In the foreground are more scenes delineated by translucent planes of either rectangular or conifer shape: an explosive event tosses up a spallation of dirt, a passenger plane flies close to the border of its restricted reality, and all around a white blankness suggests oblivion.

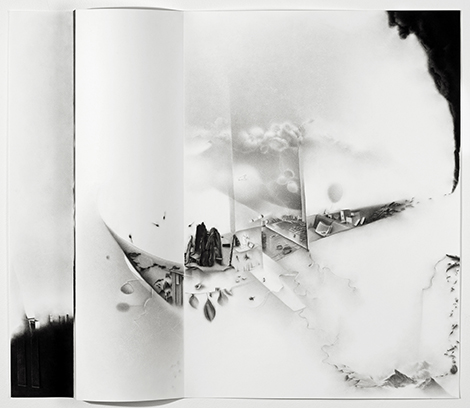

Charlotte Schulz, The uneven intensities of duration: the underside of an undigested memory appears at a time when a geological encounter begins to cast aside its boundary stones Detail (2009). Photo by Jeanette May, Copyright 2011.

Schulz gives us a unique vantage of overlapping realities in a space-time continuum that is simultaneously past and present—as though time and memory collapsed to make now a visually navigable palimpsest. We are both beneath the rock and inside the sky, coughing through the smoke and lying on a sofa to watch something burn. Ten thousand adjacent realities all arrive while an airplane flies into emptiness.

If one can’t discern from the visual clues or the rambling titles what Schulz is attempting, towards the back of the gallery are pinned a series of illustrated notes lovingly and studiously produced. They reference a raft of postmodern philosophers and thinkers including Deleuze, Irigary, Bergson, Bachelard and others. Schulz relates her tandem ruminations on concepts of eidetic space, cosmological doubling, space conceived as a realm for the play of virtualities, or a field imagined as a cat’s cradle—a game in which string figures are meant to morph into new figures infinitely.

Schulz is an established artist, having won Guggenheim Foundation and Skowhegan fellowships among others, and her considered drawings are like philosophical treatises. Actually, they are better than treatises because she uses her practice to deepen and extend theoretical propositions, to test whether they are true. Seeing this work you will believe Schulz. They are true.