“What happens to a dream deferred?” This question asked by Langston Hughes in his poem Harlem sets the stage of Charles White’s development as an artist. In 1934, and again in 1935, the teen was awarded scholarships to study art. Each time White showed up in person to accept the awards, he was informed that the scholarship not available to him. These incidents, noted in Michael Rosenfeld’s exhibition catalogue for the Charles White retrospective, paint a disturbing picture of a dream that began as deferred; however destiny had other plans. Two years later, the young artist was awarded a scholarship to study at the Art Institute of Chicago.

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s (LACMA) Charles White: A Retrospective demonstrates an aesthetic multi-lingual message; Charles White was and still is a Master Figurative artist and Social Realist, interpreting the human condition with visceral emotion. His subject matter was African Americans. The consistent message of such a monumental exhibition is White’s sensitive celebration of African American culture and courage, and his skilled renditions of the human figure—especially the head and hands.

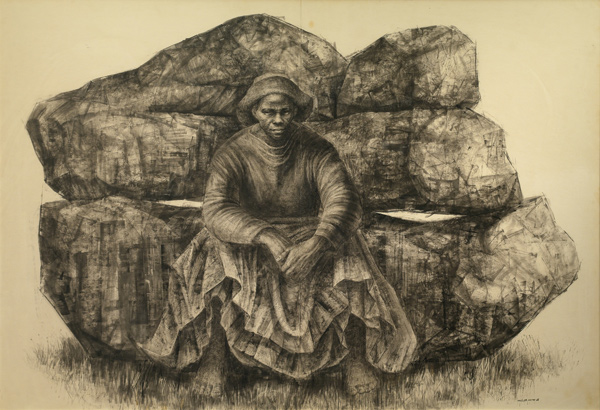

Charles White, General Moses (Harriet Tubman), 1965, ink on paper, 47 × 68 in., private collection, © The Charles White Archives, photo courtesy of Swann Auction Galleries

For example, General Moses (Harriet Tubman) (1965) honors the contribution of this black freedom fighter. Depicting her sitting in serious contemplation in contrast to her tireless work as “conductor” of the Underground Railroad indicates White’s genius; he understands the value of reflecting on one’s history. The gestural quality in this ink drawing on paper of the head and hands complements the circular centered composition. However, it is White’s appropriation of chiaroscuro in the folds of the subject’s clothing that causes kinetic movement within a sitting pose. The overall implied message in this work suggests a leader resting with regard to all that was accomplished in the name of self-determination.

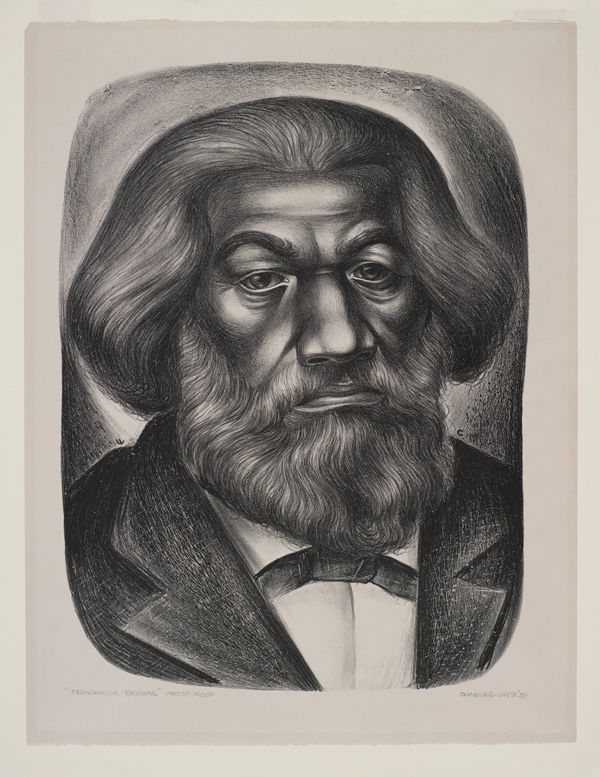

Charles White, Frederick Douglass, 1950, lithograph, 22 5/8 × 16 7/8 in., Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of Sylvia and Frederick Reines, © The Charles White Archives, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

The lithograph, Frederick Douglass (1950) pays tribute to the heroic freedom that this social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer and statesman fought for after escaping slavery. White’s meticulous modeling of this black leader’s facial features and intentional choice of portraying him as serious rather than smiling is a reminder that the battle for human dignity is momentous and unceasing. In fact, this artist’s careful drawing of the eyes challenge historical amnesia and laziness within the discipline of knowing the anatomy of the face.

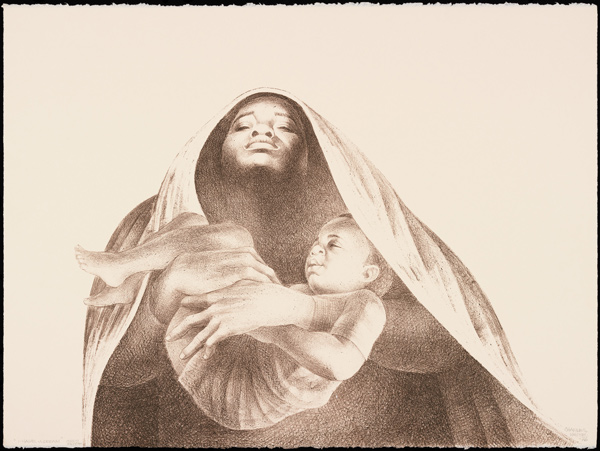

Charles White, Hope for the Future, 1945, lithograph, 18 7/8 × 12 11/16 in., The Museum of Modern Art, New York, John B. Turner Fund, © The Charles White Archives, digital image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY

White’s lithograph, I Have a Dream (1976) stirs admiration regarding its title reference and embraces the challenge of raising an African American child in a society known for its historical discrimination based on the color of one’s skin. The triangular composition guides to the focal point—a mother with a child in her arms. Gazing upward, the hope shown in her eyes connects to the 1963 I Have a Dream speech Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered before thousands at the climax of the historical March on Washington. Born in 1918 and from Chicago, White is no stranger to the discrimination experienced by black people; even so, the ability to dream in the midst of dreams being deferred echoes in this work. The underlying hope and courage embodied in this image illuminate White’s capacity to speak with a powerful visual rhetoric while cultivating the “response-ability” to develop one’s artistic talent.

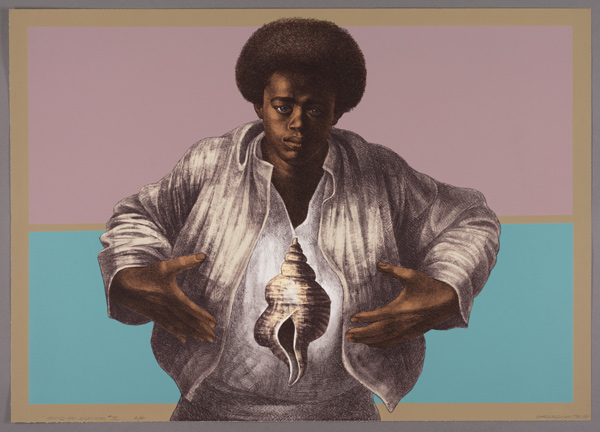

Charles White, Sound of Silence, 1978, color lithograph on white wove paper, 25 1/8 × 35 1/4 in., The Art Institute of Chicago, Margaret Fisher Fund, 2017.314, © The Charles White Archives, photo © The Art Institute of Chicago

Another lithograph similar in theme is Hope for the Future (1945). The angular, cubist stylistic rendition of the sitting mother holding a child in her lap in what appears to be a room speaks of protection. Her oversized hands shout the strong guidance and empathetic affection required to nurture hope in a black child growing up in the America during 1945—nearly 20 years before the Civil Rights Movement. As in the previous works discussed, neither mother nor child is smiling. Serious optimism is sometimes necessary when social and economic conditions imply the opposite.

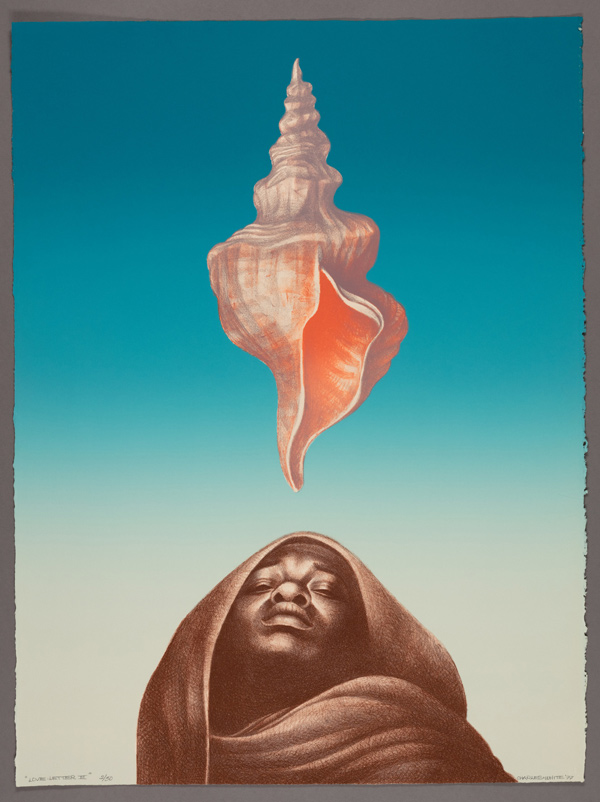

Charles White, Love Letter III, 1977, color lithograph. 30 1/16 × 22 5/8 in., The Art Institute of Chicago, Margaret Fisher Fund, 2017.291, © The Charles White Archives, photo © The Art Institute of Chicago

These four works by White showcase an artist at the height of his power, both technically and expressively. The sensitivity of the drawn hands and dignity mirrored in the faces tell positive stories for generations to appreciate. His work broadcasts to the planet that Black Lives Still matter. Ultimately, Charles White: A Retrospective foreshadows what is necessary for all human beings—historical memory and the tenacity to seize one’s destiny.

Charles White: A Retrospective, 5905 Wilshire Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90036. www.lacma.org

0 Comments