Both love letter and indictment, “The Modernist,” Catherine Opie’s new photographic installation and short film, blurrily overlays real places and occurrences with imagined events, creating an alternate near-term history of Los Angeles. Known as a portraitist and documenter of strictly factual people and communities, with this project the artist has ventured into the construction of a fiction that is loosely a portrait of the city she calls home. “The Modernist” is also broadly informed by the international and domestic political landscape, fueling a mounting sense of outrage.

As an homage to Chris Marker’s 1962 post-apocalyptic short film La Jetée, Opie’s film is neither as inventive nor as convincing as Marker’s psychologically harrowing tale of time travel and the sacrifice of the individual for the collective.

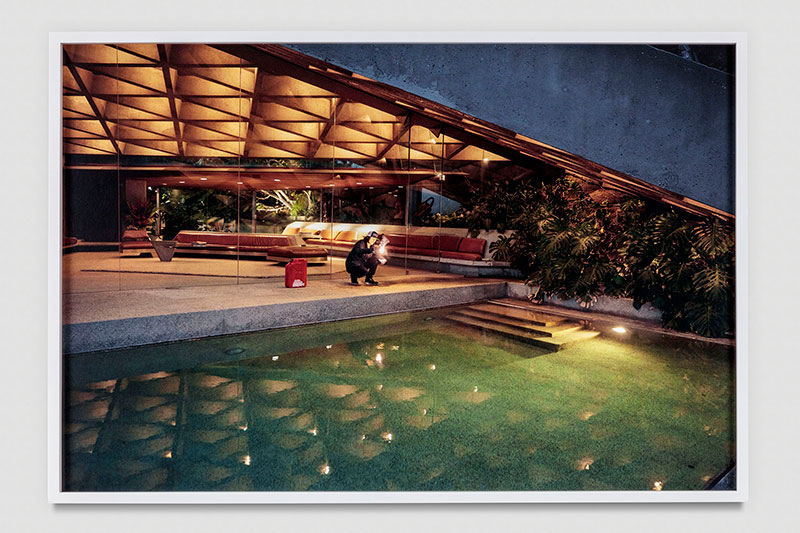

Installation view of Catherine Opie The Modernist at Regen Projects, Los Angeles, photo by Brian Forrest, courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

Yet “The Modernist” strikes home on its own terms. Opie knows how to set a scene well, engaging with the interplay between iconic images and the underlying nuances that either belie or give rise to mythologies—a continuing motif in Opie’s work that handily lends itself to spinning a tale. The films share an ambience of dread, and although The Modernist reflects the economic and political malaise of our own era, La Jetée’s Cold War nuclear terror—tempered with pallid resignation—carries an existential threat that is hard to trump (conflation intended). But perhaps that is the point: The assault on social, economic and political institutions is just as dire. (Still, North Korea looms.)

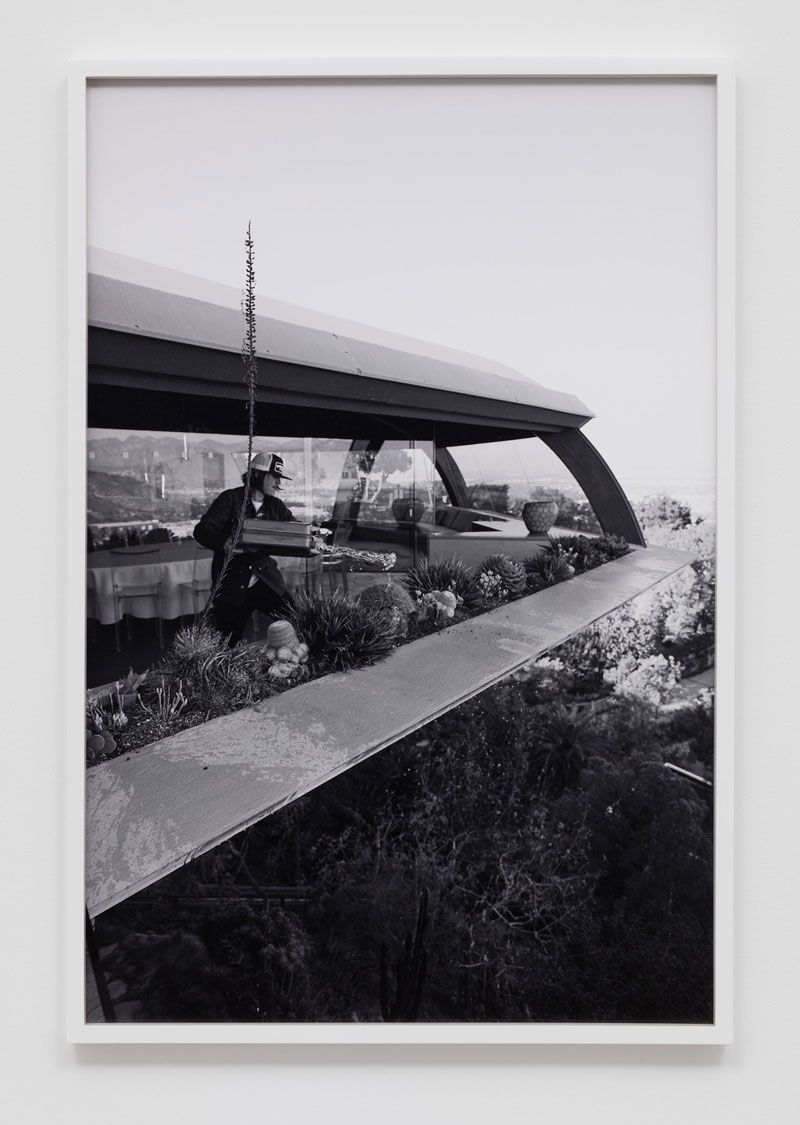

Stosh Fila, aka, Pig Pen, photographed by Opie in numerous series, inhabits the role of aspiring artist-turned-arsonist. A pristine copy of the coffee-table tome Case Study Homes sits on the protagonist’s coffee table. Using it as a kind of playbook, Pig Pen’s artist plots a campaign of destruction against the houses featured within its pages. These homes, once conceptualized as templates for affordable housing while embodying sleek Modernist design, are now emblems of luxury and privilege. Not many more than those that still exist today were built.

The arsonist’s own stunted economic mobility is spurred by a keen awareness of class stratification, signaled in Opie’s film by newspaper headlines declaring the plight of families of modest means burned out of their homes by runaway wildfires. We are meant to conclude that they are unlikely to have the resources to rebuild. Out of a sense of egalitarianism or class retribution, the artist emerges here as serial arsonist. Like so many cinematic killers, he creates an ever expanding collage of targets and trophies—presented in the gallery as an artifact of the film’s facture in the form of a collage authored by Pig Pen.

1Opie’s world-building is complete to the minutest detail. Headlines referencing real-life art stars and catastrophic losses of the architectural gems that made Los Angeles’ reputation as a locus for innovative design create a queasy sense of unreality—Opie’s film, and Marker’s too, introduces a hallucinatory motif. It’s difficult to tell which headlines are factual, and which, for the purposes of the project, are fabricated. One could be forgiven for frantically checking to see that any number of the homes seen on the arsonist’s trophy wall are still standing. Pig Pen’s collage embellishes images of Eames and Koenig homes with painted flames. John Lautner’s Chemosphere and Sheats-Goldstein Residence feature prominently as arson casualties and are photographed in situ. (Lautner hated Los Angeles, but it was his laboratory. He was remarkably responsive to client needs and budgets, and profoundly sensitive to site and the integration between structure and environment, as seen in the realization of the Sheats-Goldstein Residence’s indoor/outdoor aesthetic.)

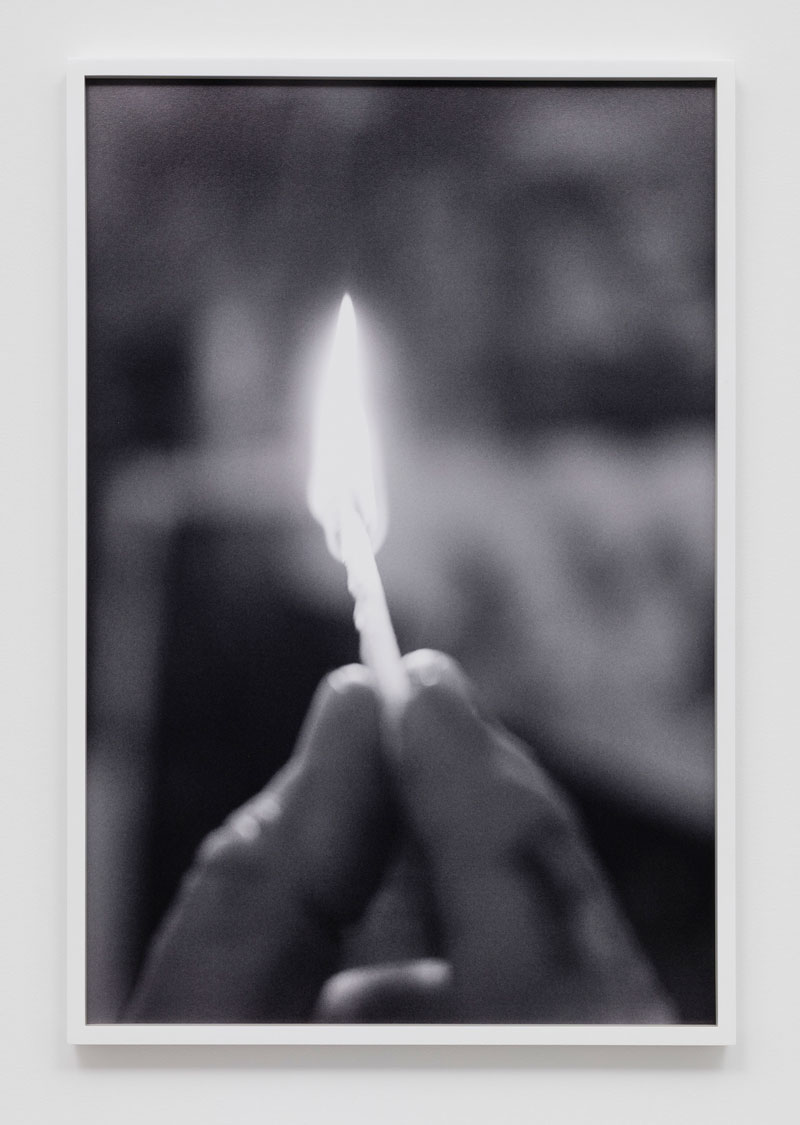

The theater for Opie’s film, an elegant rectangular prism with rounded corners and reflective sheathing installed in the center of the gallery, was designed by architect Michael Maltzan, who also designed Regen Projects. It is a modernist temple meant to evoke facets of the structures seen in Opie’s photographs and film. The exterior skin distortedly reflects Opie’s photographs that hang in the gallery. In the far gallery, a vitrine displaying a luxe collector’s box with the film DVD

and a box of Swan Vestas (the brand of English matches so prominently featured in the hands of Pig Pen’s pyromaniac), compacts the experience into a market gesture.

“The Modernist” cumulatively adds up to a complex set of “truths” not unlike the way Opie’s portraits of real people and communities offer nuanced ways of perceiving their subjects, commenting on both the exigencies of art making and the failures of modern architecture’s utopian dreams. The failure of those dreams provides the undertow in Opie’s work.