Your cart is currently empty!

Category: Uncategorized

-

OUTSIDE LA: Psychopathia Sexualis, Overgaden Copenhagen

The Pathologization of Queerness Does not Begin nor End with Gay Men“All men are gay,” reads the cover of a newspaper from Bøssehuset (The Gay House). The newspaper is part of the exhibition Psychopathia Sexualis at the art space Overgaden in Copenhagen, which displays a combination of archival material and contemporary art—the former taking center stage in a round, colorful display case and on freestanding flat screen TVs. An abstract mural covers the gallery walls alongside artworks thematically revolving around IVF, HIV and the HIV prevention drug PrEP. In 1981, homosexuality was officially removed from the list of mental disorders in Denmark. It was also the year that the US Center for Disease Control (CDC) published an article on a disease detected in Los Angeles that would later come to be known as AIDS. From one kind of pathologization to another.

Installation view, “Alle mænd er bøsser” (All men are gay) in the front display case, Psychopathia Sexualis, O – Overgaden. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Installation view, “Alle mænd er bøsser” (All men are gay) in the front display case, Psychopathia Sexualis, O – Overgaden. Photo: Anders Sune BergWhether the focus is the psycho pathologization of queer people, the HIV/AIDS pandemic, or the intersection of the two, Psychopathia Sexualis is heavily focused on a gay male perspective. It fails to recognize trans people as more than a commercialized footnote with the inclusion of a couple T-shirts in the souvenir-like collection, with hollow statements such as “We should all be trans” and “I am non-binary”. Transness was considered a mental illness in Denmark until 2017 and is still treated as one, requiring psychiatric examinations that can take years to complete due to long waitlists, in order to access treatments such as hormones, surgery, and speech therapy. In the US, The American Psychological Association (APA) only this year acknowledged that being trans or non-binary should not be considered a mental disorder.

Installation view, Psychopathia Sexualis, O – Overgaden. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Installation view, Psychopathia Sexualis, O – Overgaden. Photo: Anders Sune BergAs for HIV/AIDS, trans people, sex workers, and intravenous drug users were and still are heavily impacted by the virus, as well as gay and bi people. Maybe this is part of the question artist Brendan Fernandes poses, “In PrEP we trust?”, because who can actually access this HIV prevention medication? Yet, in an exhibition that does not appear scared of being explicit, trans people, sex workers and intravenous drug users should not be relegated to a mere potential subtext. The reason for including sex workers and intravenous drug users is not only the big overlap between these groups and LGBTQIA+ people, but also the fact that queerness must include, or at the very least intersect with, class. What would it mean to redistribute PrEP and hormones amongst ourselves; not to ask for inclusion in a system that still sees us as sick depending on our proximity to a white, cisgendered, heterosexual bourgeoisie—but rather to take matters into own hands to create queer liberation? Psychopathia Sexualis is doing an important piece of work in introducing the pathologization of queer people to the Danish art scene, but let us not allow this narrative to be one of normalization and proximity to privilege. All men are gay but not all queers are gay men.

Featured image: Brendan Fernandes, In Prep We Trust?, 2016, poster

https://overgaden.org/en/udstilling/psychopathia-sexualis-2/

The exhibition is open until 10 October 2021 at Overgaden, Overgaden Neden Vandet 17. DK-1414 Copenhagen Denmark. It is curated by Mathias Kryger and features Zoltan Ará, Filip Berg, Karim Boumjimar, Elmgreen & Dragset, Nicolas Maxim Endlicher, Brendan Fernandes, Sidsel Meineche Hansen, Katrine Dirckinck-Holmfeld, Cassie Augusta Jørgensen, Carlos Motta, Niels Nedergaard, Maria Thastum, Maria Wæhrens.

-

Tribute to L.A. Sculptor Kenzi Shiokava (1938-2021)

L.A. sculptor Kenzi Shiokava died June 18 at age 82. His passing was announced by the Japanese American National Museum. JANM featured Shiokava’s totemic wood sculptures in the 2017 Pacific Standard Time exhibition “Transpacific Borderlands: The Art of Japanese Diaspora in Lima, Los Angeles, Mexico City, and São Paulo.” The artist was an ideal fit for the show. Born to Japanese immigrant parents in Santa Cruz do Rio Pardo in the state of São Paulo, Brazil, at age 25 he followed his sister to Los Angeles in 1964.

The young Shiokava enrolled in the Chouinard Institute (now CalArts) focused on painting. Fulfilling a sculpture requirement his senior year of 1972, he struck upon his life’s work: Carved found wood, arranged vertically in clusters. He went on to earn his MFA from Otis Art Institute (now Otis College of Art and Design) in 1974. From small found wood pieces such as railroad ties, he moved up to sections of tree trunks and telephone poles, often several feet above head height. He tapered them and hollowed them out using only hand tools. He appears to have arrived at many a form by carving away sections of burnt wood to reveal the contrasting unburnt wood beneath. The totems seem both ancient and modern. Mixed in with these form-centric works are assemblages–wood pillars with cascades of macramé, electronic wires and found materials both organic and non. The artist was influenced by L.A.’s Black assemblage artists, his contemporaries, including John Outterbridge, Noah Purifoy and Betye Saar.

Kenzi Shiokava. Installation view, Made in L.A. 2016: a, the, though, only, June 12 – August 28, 2016, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest. Shiokava made a living as a gardener, notably for Marlon Brando, while maintaining a studio practice in Compton,. (Brando acquired one of his sculptures, as did Jack Nicholson.) He showed at such local institutions as the Watts Towers Arts Center and even MOCA but was not widely recognized until he was 78 years old. It was then that the Hammer Museum presented a large installation of his work in the 2016 Made in L.A. biennial. Nothing else in the museum-wide exhibition came close to his singular, fully-realized vision, honed over decades. Opening night found the artist overcome with joy. As new admirers approached to congratulate him–many stooping to meet his eyes, as he stood under five feet tall–he threw his arms around them, the lei at his neck swinging. Visitors voted him best in show via voting stations around the museum, earning him the Mohn Public Recognition Award of $25,000. L.A. Times art reviewer Carolina A. Miranda declared Kenzi Shiokava the biennial’s “breakout star.” In a KPCC Off-Ramp interview during the exhibition’s run, he said, “Now I know my work is going to survive me.”

-

SUMMER READING: Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto

Reviewed by Pelumi OdubanjoSUMMER READING: July-August 2021

Digital Special Edition Review

Subscribe or Order to Get Your Copy TodayGlitch Feminism: A Manifesto

Reviewed by Pelumi OdubanjoA ‘glitch’ is often considered to be an error; a malfunction that appears to temporarily cause or indicate fault within a (digital) system or machine. Rarely is a glitch considered to occur beyond the realms of cyber-space. Is it possible for the ‘glitch’ to be embodied? And in such, is it possible for the glitch to be used as radical practice?

The answer, in short—according to Legacy Russell—is yes. In Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto, the rousing debut book by American curator and arts writer Legacy Russell, the glitch is defined as a creative strategy informed by and for queer, trans, nonbinary, and non-white communities that are systematically oppressed by capitalist, heteropatriarchal forces. Using the trope of a political manifesto rather than a long-form essay to bring narratives of marginalised individuals to light, Russell unravels the various ways that liberation can be found within the fissures between race, gender, and technology.

Legacy Russell. Photo by Mina Alyeshmerni. Image courtesy Verso Books.Opening the text through a memoir-like transit, Russell describes what the internet once represented throughout her adolescence as a Black, femme queer woman. Russell, who was born and raised in New York City, spent her formative years roaming the internet. Online, through “storytelling” and “shapeshifting,” Russell “found [her] first connection to the gendered swagger of ascendency, the thirsty drag of aspiration” The internet held Russell’s experiments with queerness, femmeness, and blackness as a space where she was able to become “digital Orlando…shapeshifting, time-traveling, genderfucking as [she] saw fit.”

Infusing memoir and Black feminist theory, Russell paints an image of a physical world unequivocally entangled by the cyber-realm. Concerned with how race, gender, and sexuality influence and affect the way that our identities are performed, Russell’s glitch is to be understood as a political framework; one which precedes any gendered economy and one which, as it enters and is performed, registers a resistance. Such a strategy provides a necessary resistance for those bodies that have been ignored, side-lined or considered “faulty” by hegemonic culture. As she writes, “a body that pushes back at the application of pronouns, or remains indecipherable within binary assignment, is a body that refuses to perform the score. This non-performance is a glitch. This glitch is a form of refusal.”

Glitch Feminism recaptures the rallying cry of early cyberfeminism. First theorized by the cultural theorist Sadie Plant in the early 1990s, cyberfeminism was defined as “a movement which sought to re-theorize gender, the body, and identities in relation to technology and power.” Though Russell does not go in-depth in referencing Plant or fellow “cyborg” Donna Haraway, the thread is evident. Central to early cyberfeminist thought were the ways that the digital realm could present a techno-utopian field to enact the aspirations of radical feminism. However, cyberfeminists often failed to register how their liberatory efforts were modelled strictly on their exclusions—those of white, cis womanhood. Russell recognises that as Black and queer people, the digital space can hold varying liberatory practices, acting as a site for collective gathering, a space for interrogating and congregating, and as a place for nightlife and partying. Russell actively chooses to not center the activity of these early cyberfeminist thinkers in Glitch Feminism, but reaffirms this thread through its refusal to be pinned down to a singular context. In doing so, Russell perfectly contends that Glitch Feminism is, in fact, a part of that history.

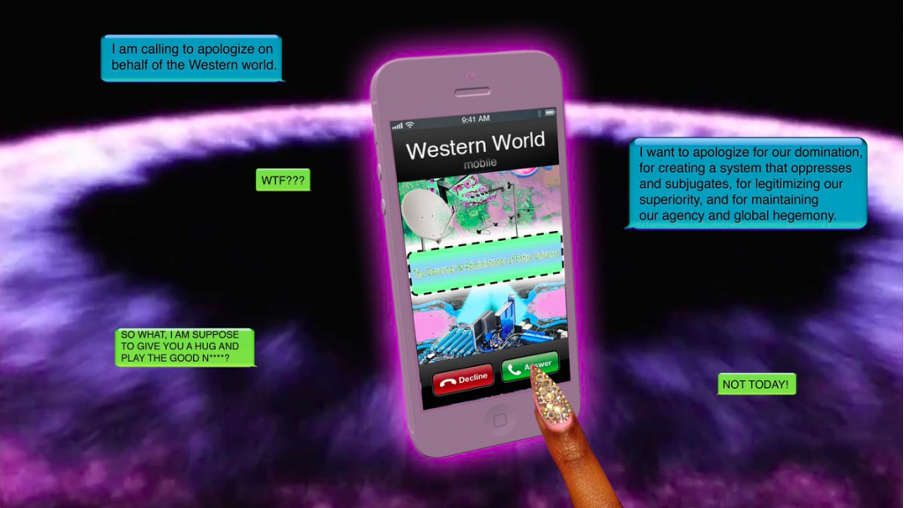

Still from Tabita Rezaire, Afro – Cyber Resistance (2014). Image courtesy of the artist.Building a strong scaffolding around her manifesto, Russell interweaves various works from multidisciplinary artists, offering a multitude of creative practices that are informed by the glitchy porousness of cyberspace. Including pieces by Ocean Vuong and Sondra Perry, amongst others, each work acts as an interlude for the narrative, aptly breaking up Russell’s train of thought, yet never throwing the reader off. Much like her curatorial practice, Russell creates an artistic landscape that defies chronology and linearity, uniquely rebelling against the patriarchal framing of history.

Glitch Feminism asks us to interrogate the possibilities of an online world. The glitch is no longer “an error, a mistake, a failure to function.” Rather, the glitch actively decodes, unravels, and ultimately ruptures our notions of the digital realm, revering it as a space where the self is found through constant metamorphosis. Russell throws out several intriguing incitements, and in many cases I found myself wanting Russell to complicate and deepen these ideas. However, Glitch Feminism is at its best in these moments of humming assertion. Russell wields language as an artwork in itself, creating a philosophy grounded by a utopian vision, wherein the glitch stands as the first step towards a freedom built on error and revolt.

Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto by Legacy Russell

192 pages / August 2020 / VERSO Books -

Alexander Harrison

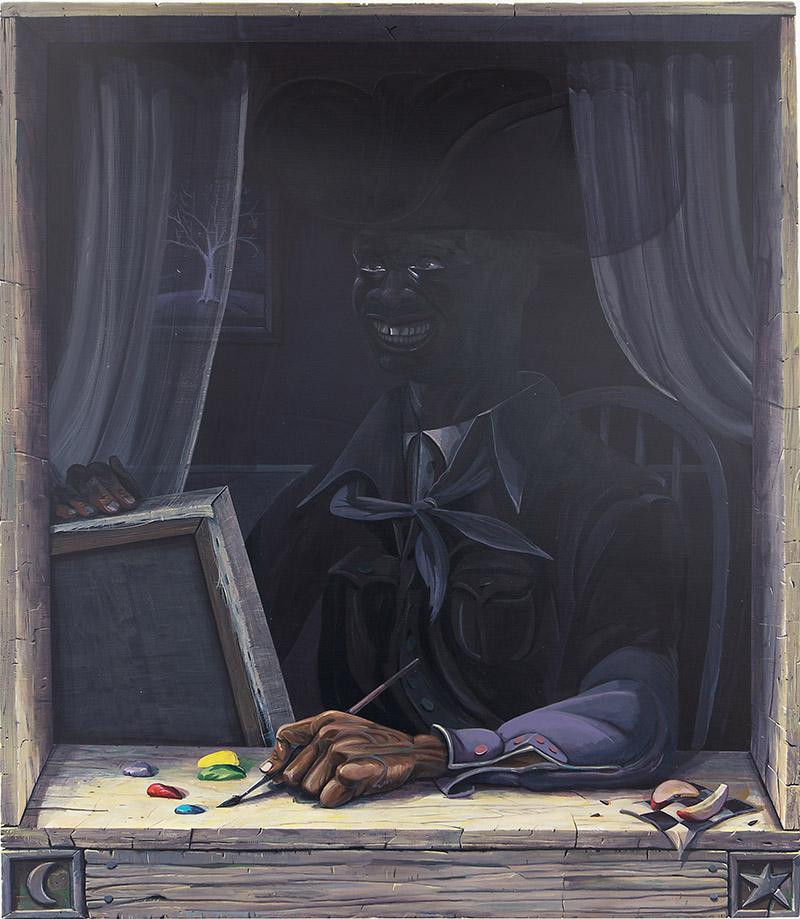

Various Small FiresAlexander Harrison’s aptly named exhibition “Midnight Everywhere,” is an exploration of the moods, tones and colors that the night brings. The paintings in the exhibition form a cohesive collection and tell the story of a solitary artist living in an old wooden house in the middle of nowhere, surrounded by apple trees and rolling hills with only the stars and flowers to keep him company. The focal painting, Portrait of an artist in the penumbra of the moon, in hopes for a brighter future (all works 2021), gives insight into who the main character in this story is—a Black cowboy with a toothy grin gazing out the window, painting the midnight sky.

In many ways this “artist character” gives the collection a meta quality. Although the paintings were created by Harrison, one could suspend their disbelief and instead infer that the paintings were in fact painted by this mysterious cowboy. The still life paintings of watermelons, apples and flowers are what he would paint after a long day, and show snapshots from his life, giving the impression that this cowboy could have simply looked around his environment and painted what he saw in his surroundings. The consistent color palette is effective: the deep blues and purples give the impression of moonlight spreading over each scene. It’s easy to visualize the quiet, secluded cabin in which all of this introspection and recording took place, and to fill in the blanks of who this artist is (the one in the painting, not Harrison himself). The cohesive story is echoed by repeating themes in the paintings, such as checkerboard cloth, or watermelon seeds from a windowsill in Midnight Picnic, which also make an appearance in The Moon.

Alexander Harrison, Counting Sheep, 2021. Courtesy Various Small Fires. All of this storytelling elevates the show to a metaphysical level, and changes the context of the figurative paintings that contain subject matter that could be seen as elementary—how many art students paint fruit for their first assignment? This does have its downfall, however, as the pieces are stronger as a collection and some may not hold up as well as solo efforts. This is a show that is greater than the sum of its parts.

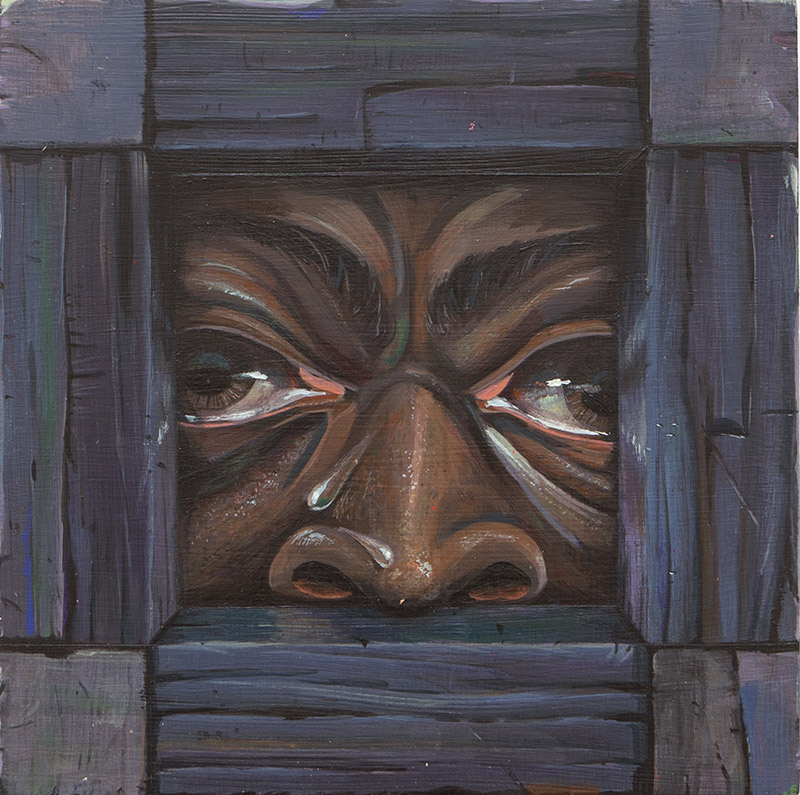

Harrison’s interest in storytelling goes beyond the paintings’ content, and into his painting techniques as well. Many of the paintings have a trompe-l’œil effect, in which Harrison has painted frames around the composition. This strategy suggests a vantage point from within the painting, further immersing the viewer in the world he has created. The windows also tell another story, as sweeping landscapes and a sense of stillness are juxtaposed by imagery of one being trapped. In Counting Sheep, a face peers out of a tiny opening, and in Why’d I have to Go n’ Dream so Big? the windowpane suggests a jail cell. This obvious longing that the artist in the paintings has is palpable, and from the solitary Light of Mine in the room of its own, it appears that the fire is still burning.

-

Stephen Cohen (1948–2021)

In RemembranceStephen Cohen, a long-time Los Angeles gallerist and the founder of one of Southern California’s most enduring art fairs, PhotoLA, died on February 25th, 2021 from complications related to cancer at the age of 72.

A charismatic fixture on the LA art beat, Cohen quietly slipped away without getting a chance to say goodbye, leaving behind an important forum for photography that he helmed for decades. It was an unexpected departure for the lovable hypochondriac, as his quick exit came as a surprise to many in the art world. To the people who held him dear, it was a gut-punch; and for those who had their criticisms, it surely served as a blunt reality check. Either way, his loss can’t help but be compounded by the weight of this very strange time of adversity and affliction. Now more than usual, the memory of his uninhibited, wide-eyed curiosity for photography is a reminder of the bonding power of art and an occasion to reflect on the community that he helped foster around it.

Stephen on the left, with his brother. Cohen was a centralizing figure in the photo world for a long stretch of time, a unique personality in a field full of real characters. He started organizing art fairs in the early 90s, beginning with Photo LA which was the first and is still the longest running photographic art fair in Los Angeles. At a time when photography was still considered a second cousin to art with a capital “A,” it began as a small, intimate event with just 25 vendors gathered for a weekend affair at Butterfield’s & Butterfield’s on Sunset Blvd. It grew quickly, more than doubling in size, to become a standout on the art fair circuit, one of very few on the West Coast that was truly global in scope and that managed to make a real stand long-term. It saw many iterations with stints at the Santa Monica Civic Center, The LA Mart, and Barker Hanger (where it still takes place), and spawned many offshoots: Photo Santa Fe, Photo San Francisco, Photo NY, Photo Miami, and ArtLA. His fairs cemented a local tradition — 2022 will mark the 30th anniversary of PhotoLA — with Cohen usually at the heart of it, drawing notables from near and far. Ultimately, his efforts laid the groundwork for what would become the month of photography and fixed January as art fair season in the City of Angels.

Long before the fairs though, Cohen was a young, aspiring creative from New York City who heard the call of Hollywood. Fresh from Brooklyn College with a degree in art and photography, he headed out west in 1969 to study cinema at the famed USC Film School. There are mythic stories of his early days in LA, making ends meet as a driver for big stars like Barbara Streisand and Leslie Ann Warren. With the movie industry always at his front door, the impulse for storytelling never really left him. Eventually though, as he set out to establish himself as a photographer, he landed in the business of collecting and reselling photography books, and eventually prints. It wasn’t terribly lucrative, but he loved the hunt and turning up works by unknown and forgotten artists. By 1979, he dipped his toes into the LA gallery scene assuming the role of director at the artist cooperative, Cameravision, before returning to private sales two years later and taking the show on the road. From 1985 to 1991, Cohen crisscrossed the country bringing his discoveries to curators and collectors in smaller art markets like Kansas City, St Louis, Atlanta, Chicago, and Minneapolis. He also spent a good chunk of time in New York, selling downtown artists to uptown galleries for a premium. He was content being the middleman and tickled by the reputation he garnered for being able to sell almost anything.

True to form, Cohen was always making a deal. Whether it was selling a print or a booth, he couldn’t help but see opportunity all around. His style as a dealer could be a bit cheeky, but he was really earnest about the work he loved. Genuine excitement pierced through every transaction. Whether he was looking at emerging talent or old favorites, he saw it all with fresh eyes like it was the first time. He was a rare bird, though, and he ruffled some feathers along the way, usually in such an ingenuous way that made it difficult to stay mad. He could pitch a fit for seemingly random things — a phone bill, a lost post-it note, Fox News — and the smallest annoyances could send him into a glorious tizzy! Most anyone that worked with him at his eponymous gallery — first, in a tiny, second-floor space in a courtyard-style complex and later at the well-known storefront on Beverly Blvd. — got a taste of his mercurial temperament, but could also attest to the warm, familial vibe of the place.

Stephen in Miami Beach, FL, at the Miami Fairs, circa 2015 The gallery, where he was neighborhood institution for over 20 years, championed the work of numerous distinguished artists with shows of vintage works by popular masters like Arthur Rothstein, Dick Arentz, Tom Arndt, Horace Bristol, Ida Wyman, Louis Faurer, Edmund Teske, Tseng Kwong Chi, Daido Moriyama, Walker Evans, Ken Ohara, and Vivian Maier. His program also highlighted contemporary works with a broad mix of heavyweights including: Lynn Geesaman, Luis González Palma, Lauren Greenfield, Nick Brandt, Victor Cartagena, Pieter Hugo, Amy Arbus, Olaf Otto Becker, Lori Nix, David Levinthal, Anthony Friedkin, Roger Ballen, Arthur Taussig, Judy Gelles, Larry Clark, Larry Fink, and Siri Kaur.

Stephen was well-known for his sweet tooth! While the gallery was often a hub for artists to drop in for a tour and a chat, it also served as the headquarters for Cohen’s fair operations and was the nexus of all kinds of cross-pollination. From a celebrity guest host to a hired hand, a frequenter with a passing fancy, or even those at the tippy top of photo world food chain, Cohen seemed to know everyone. In its heyday, the gallery was an unusually welcoming clubhouse and Cohen was like a sheepdog nudging acquaintances together. He loved to be in the mix and make things happen. A creature of habit, he took pleasure in the regular ritual of producing fairs and exhibitions — the flurry of installations, hobnobbing at the openings, even the de-installs after grueling week-long fairs, and probably most of all, the promise of rewarding rendezvous around breakfasts, lunches, and dinners.

The only thing that captivated Cohen’s attention as much as art, was food (and possibly politics which he frequently failed to keep under his hat). But, any irascibility could be overcome by his passion for the tastiest grub and his schedule was often built around what and where to eat. Favorite spots figured prominently in his life like good old friends, and it made no difference if they were fancy or down-home. He made a practice of patronizing his most beloved eateries everywhere he went. It might be El Coyote down the street for an impromptu happy hour; Enriquetta’s on the last day of the fairs in Miami; or a mission to Katz’ and Zabar’s during the New York art fairs in the spring. The delight and comfort he took in the routine of sharing a meal made him relatable, unapologetically human, and imminently likable.

Although Cohen was endeared to many and connected all sorts of people, he himself lived a pretty solitary existence day-to-day with the exception of his adorable little pup, Fez. He never partnered and mostly made do alone, but he was always rich with the company of his prints and books, and a strong sense of purpose. He could seem uneasy in his own skin sometimes yet strangely fond of his own personal weltschmerz, almost enchanted by the darkness.

Sweet and coy, stubborn and indelicate, a hopeless grump and still an unflappable optimist, Cohen got away with being a happy recluse and still managed to be the glue that kept a big group of photo-loving friends and colleagues coming together year after year. For a lot of photophiles and fairgoers, it might be hard to picture the crowd without him when the world opens up again. While his absence will certainly be felt, especially by his favorite brother, Michael, he will still be with us and his legacy will carry on in the community he helped make possible.

Photos provided by close friends and family.

-

In Memory of Roland Reiss (1929-2020)

We are saddened to announce the death of Roland Reiss, artist and educator, loving husband, father, and grandfather, who passed away on Sunday, December 13, of natural causes in Los Angeles, at his home and studio at The Brewery Artist Lofts. He was 91.

Reiss is widely known for his miniatures but is foremost a painter. An influential and beloved voice in the Los Angeles and Southern California art scene, Reiss exhibited widely throughout his sixty-year career. He was included in the 1975 Whitney Biennial, documenta 7 (1982), and received fourteen solo museum exhibitions, including The Dancing Lessons: 12 Sculptures (1977) at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. A retrospective at the Begovich Gallery at Cal State Fullerton (2014) highlighted his career of continual self-reinvention, which led to a groundbreaking body of work.

It was a privilege to work with Roland in recent years, and we were thrilled to present four solo exhibitions of his paintings, miniatures, and early works on paper. His earliest work was influenced by Abstract Expressionism, but Reiss brought new plastic materials popular during the 60s in LA into his early paintings. However, the Conceptual art movement of the 70s opened up a new world to him, one where “content” mattered.

Roland Reiss, “Number 9” from The Dancing Lessons: 12 Sculptures, exhibited at Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1977. He began to explore human drama in miniature tableaus encased in Plexiglas. Viewers were invited to interpret the myths of modern American culture, from actual murder cases to life in the corporate world by entering a scene frozen in time. Reiss condensed “a complexity of ideas in a single piece.” For the past twenty years, Roland devoted himself almost entirely to floral paintings, working through series as a meditation on the impact of color on consciousness. He described this body of work as an effort to “put everything I have learned about painting into a painting.”

He showed with Cirrus Gallery, Ace Gallery, and Diane Rosenstein in Los Angeles; and with Rena Bransten and Toomey-Tourell Gallery in San Francisco. His miniatures, sculptures, and paintings are included in the permanent collections of Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA), The Hammer Museum, The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Orange County Museum of Art (OCMA), Palm Springs Art Museum, Laguna Art Museum, Riverside Art Museum, among others.

Roland Reiss was born May 15, 1929 in Chicago, to Martin and Louise (Strum) Reiss. A self-described “Depression baby,” he moved with his family to Pomona, California during WWII. As a young man, he quickly devoted himself to the study and practice of art, and he was introduced to Millard Sheets, who came to speak to his class at Pomona High School. He attended the American Academy of Art, in Chicago, then returned to Pomona to study art at Mt. San Antonio College. After graduation in 1952, he was drafted into the army during the Korean War. He married Betty Ravenscroft, the mother to his six children, and then was stationed at Camp Roberts, just north of San Luis Obispo. A Sergeant First Class in the US Army, he served as the art director for forty artists working at the base. He painted a mural, which received commendations, and along with Robert Irwin, a fellow GI, he won a national Army art prize. Soon thereafter, his orders to transfer to active combat in Korea were cancelled.

He believed that art saved his life.

Roland Reiss “Domestic Setting,” 2014. He enrolled at UCLA on the GI Bill, where he met artists Charles Garabedian, Ed Moses, Craig Kauffman, Ray Brown and James McGarrell. He took his graduate degree and MA in art in 1956. While at UCLA, Reiss assisted the artist Rico Lebrun; and was taught by William Brice, Jan Stussy, Stanton McDonald Wright, and Anita Deland. In 1956, he took the position as senior painting teacher at the University of Colorado at Boulder. Here, he brought Clyfford Still to teach for a summer, followed by Richard Diebenkorn, Joan Brown, Nancy Graves, and Hilton Kramer, all who became friends. In the summer of 1966, Roland Reiss and Richard Diebenkorn returned to Westwood, as visiting artists at UCLA.

Roland moved back to California in 1971 and headed the art program at Claremont Graduate University for the thirty years, retiring in 2002. At CGU, he devised a community-centered approach to the grad program, earning it national recognition. After his retirement from CGU, Reiss directed “Paintings Edge,” a summer artist’s residency in Idyllwild from 2000-2007. In 2009 he received the College Art Association Award for the Distinguished Teaching of Art. At CGU he held the Louis and Mildred Benezet Chair in the Humanities and in 2010 an endowed chair in art was established in his name.

In 1991, Roland married artist Dawn Arrowsmith, who was by his side when he passed away. They had been together for thirty-eight years, and their relationship, she says, was ‘a daily love affair.’ He was preceded in death by his father, Martin, his mother, Louise, his daughter Noel, and his son Clinton. He is survived by his wife; his four children, Adam, Nathan, Talya, and Stefan; stepsons Dan and Jim Nielsen, his sister Marilyn Austin; and his grandchildren, Mitchel, Tessa, Annika, Tatum, Freya, Lindsey, Brody, and Blake.

A Celebration of Life will be announced when we can gather again safely.

-

PROVENANCE

The Watts Riots, Nickerson Gardens, and Black Lives MatterIn 1965, angry, fed-up citizens took over Watts, a historically Black neighborhood in South Los Angeles. Similar to the recent Black Lives Matter (BLM) uprisings, the Watts Riots began after police responded to a minor infraction with violence, arresting two Black men at a traffic stop. Enraged, thousands of Angelenos took to the streets to protest the latest instance of police brutality. Over a period of six days, the riots resulted in 34 deaths, thousands of arrests and over $40 million in property damage; ultimately, it required 14,000 National Guardsmen to end it.

The Watts Riots erupted just five days after the passage of the Voting Right Act of 1965, an incredibly progressive policy that attempted to eliminate voter discrimination. But now, only 55 years later, riots are again needed to protest the unjust treatment of Black Americans. Why? What failed? Together, the Watts and Black Lives Matter rebellions reveal that no policy can ameliorate the racial violence and economic exclusion that have defined Black life since the United States’ founding.

Burning buildings, Watts Riot, Los Angeles, California, August 13, 1965 But something separates the Watts from the BLM uprisings. Unlike in 2020, in 1965 rioters focused their attentions on a Black neighborhood. Indeed, the destruction of Watts centered on the neighborhood’s large public housing communities, such as Hacienda Village (1942), Avalon Gardens (1941), and Nickerson Gardens (1955) (pictured left). The last was built by Paul R. Williams (1894–1980), a renowned Black American architect and one of the most influential mid-century modernists to work in Los Angeles. Tragically, the destruction of Nickerson Gardens underscored the death of Williams’ dream: that poor Angelenos could live dignified and prosperous lives.

Williams designed Nickerson Gardens to have 1,110 housing units that covered more than 55 acres. This design—dubbed a “superblock” because little to no through traffic passes through it—was defined by a distinctive break from its gridiron surround. The large, two-story apartments contained expansive picture windows that looked out onto the verdant space. At the project’s heart was a large community center that could seat up to 1,000 people, perfect for neighborhood theater productions or other local gatherings. Williams also included a small meeting and craft room, communal kitchen and snack bar, all of which afforded Nickerson Gardens’ residents amenities normally reserved for the wealthy. Put simply, Nickerson Gardens embodied Williams’ conviction that government-funded housing could create a better, more equitable city for its working-class citizens.

Nickerson Gardens from above. Within 10 years, Williams’ project had failed. Though Nickerson Gardens had begun as an integrated community, by 1965 nearly all of its residents were Black, which highlighted the economic disparities that segregated races. Indeed, at mid-century most Black Angelenos were poor, undereducated and forced to use crumbling city infrastructure. Following mass white flight from the urban core to the suburbs, the government disinvested in LA’s interior. As the urbanist Charles Abrams has remarked, suburbanization “redistributed [the city’s] population into areas inhabited by a new white ‘elite’ and a black unwanted.”

The Watts Riots must therefore be understood as at least partially a response to the failure of Williams’ dream—the dream to live a dignified Black life in government-funded housing. When the rioters destroyed Nickerson Gardens, they were merely transforming subtext into text: the government had long ago decided to let the project wither.

It’s therefore heartening that, today, BLM protesters decided to focus their ire on wealthy neighborhoods. Put another way, the working class has identified its enemy.

-

All of Them Witches at Jeffrey Deitch

My experience at the opening night of All of Them Witches–snaking through the costumed crowds, the abundance of art from such a wide-reach of featured artists–78!– was a maddening, sensual delight–because women, because witches. With so much to feast my eyes on, with such an excess of pagan elements, along with the as-promised, lethal-injection of witchy-sensibility, it was as if I had agreed to something beforehand, had made a deal with the devil; that to partake, required initiation, and to taste of all its delights, would cost my intimate relationship with the artist: both they and their individual work would dissolve.

I floated past the imagery of sexual awakening, of tiny rituals, and the horror of bodily change as it flashed before me; meaning, the emphasis seemed less on whose work was whose, and just why it was there, but rather a veiled cataloging with a mystical pattern I longed to divine. I registered paintings with lusty themes, witch huts, and stripper heels, shadowy women on stairwells, I repeated the names of artists I was familiar with, and artists I hoped to remember and follow, involuntarily whispering the spell. A painter friend turned to me and said, wryly smiling: you’re writing about this? How? It’s all over the place!

Gallery view courtesy of Jeffrey Deitch Los Angeles And it was. There was the impressive gathering of so many new talents I have come to love–Amy Bessone and Celeste-Dupuy-Spencer especially–and juxtaposition of old favorites like Ana Mendieta and Juanita McNeeley. Yet a part of me was unnerved. Was inviting this sort of feasting, the something-for-every-type-of-witch, opportunistic? Was the catch-all, witchy draw offering up the works themselves like the fetishized head of John the Baptist to Moreau’s Salome?

I am sensitive to the notion that Instagram has changed the built world. Posting to align oneself with cultural capital will always serve Capitalism, and serving Capitalism ruins everything. Critics have been apt to point out that the quest to be “instagrammable” not only creates an opportunity on which the institution can capitalize, but has also shifted how exhibitions are constructed and experienced — look no further than the Instagrammable popularity of Yayoi Kusama and James Turrell to see the trend enacted.

Gallery view courtesy of Jeffrey Deitch Los Angeles But sifting through all the geotags of the gallery one night, I was struck by things I still wanted to see, there were entire paintings I glossed over–the geotags were an archive of a different experience, in fact, endless permutations of experiences that could still be had. On a Wednesday afternoon, gallery-ghost hour, in late light, I returned and followed this time the breadcrumb of flame emojis that were popping up over new artist’s work, and appreciate each for myself. To once again, by following the flame, burn the online effigy, and take part in the ritual.

In certain ways, if we reduced artistic work to content, then the content of All of Them Witches mirrored the content regularly found on my Instagram discover feed. When I got to admire for myself, Amy Bessone’s Untitled (I’m Not Suzanne), the pink-bodied woman with the wet hair, the skull, and look at the way the water around the subject’s feet seemed to move, there was something affective, so much more than the content of its parts I knew a hashtag like: #skull, #witchy, #woman, #water would never yield the beauty and achievement of her paintings. But knowing that on the internet, this painting could be cataloged as such by an unfeeling algorithm, makes me think this show was an important reminder to stay vigilant in our own practices, remember what we consume, and what we conjure.

Gallery view courtesy of Jeffrey Deitch Los Angeles When I consider the coven of artists who appreciate each other, who repost and share, who feast off the algorithm for their own inspiration, and perhaps even the curators of All of Them Witches who cleverly anticipated our public witchy practice, I am brought back to Mikhail Bakhtin and his idea of carnival. Bakhtin saw the importance of carnival in its “offering a completely different, nonofficial, extraeclessiastical and extrapolitical aspect of the world, of man, and of human relations; they built a second world and a second life outside of officialdom…” He goes on to say, it “is by no means a purely artistic form nor a spectacle and does not, generally speaking, belong to the sphere of art. It belongs to the borderline between art and life. In reality, it is life itself, but shaped according to a pattern of play.”

All of Them Witches allowed all of us witches a night of the extraecclesiastical, a night free to play, and perhaps approach our relation to the world, when we exited, anew.

All of Them Witches

Organized by Dan Nadel and Laurie Simmons -

SHELTER-IN-PLACE: How Can We Revive Public and Participatory Art During Coronavirus?

Journalist Calvin Trillin once claimed that California had “a profusion of lawn sculpture…as a natural product of a large retired population and a climate that permits outdoor hobbies.” Quirky though California landscaping may be, its public art has always involved more than plastic flamingos. It also involves cats and crocodiles.

Thanks to the work of the nonprofit group We Are From Dust (WAFD), a new art park at Point San Pablo Harbor contains Peter Hazel’s 40-foot long mosaic crocodile “Niloticus” and Paige Tashner’s “Purr Pods,” cat sculptures that purr when touched. The volunteer effort emerged from the dust of Burning Man, appropriately enough, to place large-scale artworks in public spaces.

WAFD’s leaders aim to create an afterlife for the large-scale installations that are part of the yearly desert festival, as well as other works of “participatory art” that are created or experienced collectively. “We believe that art is one of the most important cultural drivers for social interaction and positivity,” Will Chase, one of WAFD’s leaders, says. Their goal is to transfer the energy of Burning Man into the ethos of making public, participatory art both accessible and sustainable.

Image courtesy of We Are From Dust “We’re in a time where human connection is precious, and it’s also been so severely distorted,” Chase said. “[Art is] more important than ever, given everything that we’re in, but it’s also going to be…the least prioritized.” In this period, he says, “People are…reinventing everything. So the question falls to us, ‘Well, how do you reinvent art?’”

According to Chase, no one has the answer just yet. “We’re all still figuring out where our ass is and our elbow is,” he says. But “our goal is to see what we can do to keep participatory art as a strong cultural driver and social driver through all of this.”

Marian Goodell, Burning Man’s CEO, is also a supporter of WAFD’s aims. “Their intention and their focus is so powerful and important,” she says. “Their endeavor to take large-scale art, engaging-our-community art, and to help install it in places where it can be really experienced is really powerful…That’s the real deal.”

WAFD’s efforts have made the park at Port San Pablo Harbor “a destination,” according to Goodell, with works by Kate Raudenbush and Michael Christian as well as Tashner and Hazel.

Raudenbush, whose 2010 contemplation on tech-worship “Future’s Past” is installed in the park, says she loves working with WAFD because they understand the logistics of large sculpture. “They highly respect working artists, and don’t expect artists to work for free or…‘for exposure,’ she says. “They also share my visions of the role of art in society: art can be inclusive, it has a socially connective force, and art can be a conduit to contemplate the important issues of our time.”

Image courtesy of Kate Raudenbush Tashner agrees with Raudenbush about WAFD’s push to “engage the public” with interactive art: “They’re trying to make that available to everybody, because it’s a really unique, wonderful experience.” In the time of coronavirus, Tashner says that interacting with works outdoors can be helpful even if you don’t touch or climb them just yet.

In addition to the two at Port San Pablo, one of Tashner’s “Purr Pods” has found a home at the American Museum of the House Cat in North Carolina, and WAFD commissioned another for an upcoming exhibition in Bristol, UK. “They are trying to find and help other artists, which is so wonderful about them—they have this beautiful vision of bringing [art] all over the world,” Tashner says.

WAFD has been crowdfunding to support artists during this period of slowed work and canceled commissions—especially for participatory art, which involves close contact during construction as well as use. In addition to the financial support, Chase says, “We’re lining things up in anticipation of being able to do participatory art again,” and exploring other forms of interaction such as artwork that can be controlled remotely.

Image courtesy of Kate Raudenbush Goodell’s current focus is on planning for the future of Burning Man, especially its virtual edition in 2020, but she hopes to collaborate with WAFD as well: “One of my priorities is to help support them.” The artists that are integral to Burning Man’s playa still need homes for their work, whether temporary or permanent.

In this climate, Raudenbush predicts that sculpture parks will prove more popular than ever. “I really hope to see more outdoor art exhibitions,” she says. “I believe that sculpture has a huge role in “place-making” in public spaces.” Goodell agrees. Organizations like WAFD are “creating that opportunity to appreciate one another, and to sit near art” she says. “The art’s the magnet; art’s the flame.”

“This experience of us being sheltered from each other [in quarantine] is creating suspicions towards other people, towards the stranger…so we need the bridges” that art provides, Goodell adds. “Even if you’re six feet away, it brings people near.”

-

Profile: Robert Ortbal

Rather than pursuing variations on by now familiar themes, the Sacramento and Emeryville-based Robert Ortbal follows a path that may well twist into an entirely different dimension. Recently you might find the serious and intellectual Ortbal wearing an oversized dog head, or riding a bike while in the guise of a giant rabbit. His sculptural art practice has gradually evolved to focus on “eccentric behaviors” performed in wearable artwork.

Robert Ortbal in his studio. All of us have recently been thrown into a Twilight Zone universe, and when Ortbal’s recent show “Marmalade” at Sanchez Art Center in Pacifica was, like so many exhibitions, cut short that also meant no artist talk—or did it? Ortbal, along with guest curator and former Oakland Museum Chief Curator Phil Linhares, decided to hold the talk online, via a Zoom meeting. They joined us in the form of talking heads, exchanging thoughts and alternating with intriguing images of the exhibition. A followup call with the artist allowed for a closer degree of human connection, speaking one-on-one in real-time.

Robert Ortbal, Midnight Sunset, 2015 Ortbal’s sculptural practice has always raised more questions than it answers, his installations populated with irregular geometric or biomorphic objects that writhed and crept across walls, like organic forms mutated in the lab. There remain vestiges of the scientist in Ortbal, although he allows that this was more appropriate for his earlier bodies of work, ones evoking underwater creatures or crystalline formations. His unique vocabulary remains, “my language and my thinking take place in the bending of a wire, or the coating of a surface.”

Robert Ortbal, Neverland, 2015 Growing up in the South Bay town of Campbell, a working-class suburb back before the tech boom transformed Silicon Valley, Ortbal explained to me that “you could roam somewhat feral” as a boy. Family expectations were that he followed a traditional path, his dad’s military background had led to a career as a mechanic for the airlines, and he took a dim view of his son’s artistic ambitions. Undergrad school at SF State, where Ortbal focused on ceramics, was one thing, but attending grad school at UC Davis, where noted faculty such as band Mike Henderson propelled him farther down this unconventional path, was quite another. As his father grew to appreciate the seriousness of Ortbal’s work, and just how hard he worked at it, “we eventually made peace.”

Robert Ortbal, Dumb Bunnies, 2018 Since 2003 Ortbal has been on the faculty at Sacramento State University. Each year, the Crocker Art Museum’s education department hosts U-Nite, a community outreach event. The SSU art professors are strongly encouraged to participate, however their artwork is given the short end of the stick, painters for example asked to display work on an easel in the hall. In response, Ortbal came up with an unorthodox idea. One day, as he explained to Linhares, while visiting a costume shop, he was confronted by a wall of bunny rabbit head masks. “It stuck with me,” he explained, as he devised a plan to bring 20 Dumb Bunnies (2018), rabbit-headed artists and arts professionals, to the Crocker event. They cycled over from the artist’s house, an alarmed woman they passed on the street remarking, “this is not good…” Upon arrival, they paid their way in with carrots. If Ortbal’s intention was fairly benign, not everyone was so amused, “Pissed some people off big time,” admits the artist who insists it was meant as a humorous, absurd action more than a political one.

Installation view of Marmalade. Ortbal’s most recent exhibition “Marmalade,” featured sculpture, drawings, photographs and video. In one corner of Sanchez, a collection of objects were clustered on a gray structure composed of square platforms positioned at various heights on spindly supports; Ortbal and Linhares discussed the way this finessed the need for a “forest” of intrusive pedestals, inventive installation choices have long been a key element in the work. Medium-scale sculptures consist of assorted geometric forms, each a conglomerate of segmented parts, one of lengths of cylindrical hunks of something, perhaps foam, others more rectilinear. As with earlier works, the objects gain interest in the textural encrustations applied to the surface, paints and other coatings slathered roughly here, blobbing like fungal growths there, a low-key palette of black, white and grey predominating.

Robert Ortbal, Crystalline Jester, 2015 Crystalline Jester (2015), a large multi-faceted object in earth tones, punctuated by triangular planes of red, hovers imposingly mounted on a wooden dowel. Like many of these objects, it can be worn. As the wearable art sits, inanimate, there is a sense of anticipation. Video and photo elements were virtually impenetrable in the Zoom presentation; they apparently include brief iPod footage of the artist in Bad Dog (2019) persona, peeing on the wall of the Crocker, along with Polaroids of other “eccentric behaviors”—Ortbal prefers to display these intimate in scale, to draw the viewer in.

Installation view of Marmalade. Ortbal emphasizes that the “work is shifting and embracing the idea of ambiguity and emptiness.” His work has always triggered multiple sensations and associations beyond the verbal, beyond ready comprehension. Trying to put a finger on the misty place in which these constructions reside, we discuss the “collapse of truth” and the absurdity of the past three years that informs them, along with our transition to the new virus era. The recent work presents a new mindset to adapt to—less Richard Tuttle and more Nick Cave. Ortbal’s plans for the future involve a new body of sculptural work including tiny figures absorbed into abstract environments, an eccentric world in miniature. While serious about the work, Ortbal’s practice is also imbued with a strong sense of humor, and, as Linhares said, “a pleasantness,” something we can all use more of these days.

-

SHELTER-IN-PLACE: Brigitte Lacombe

Photography from a DistanceDuring the pandemic, celebrity portrait photographer Brigitte Lacombe has been sheltering in place in Northern California. Accustomed to working on film sets, theater productions, fashion campaigns, and glossy magazine spreads, Lacombe has used the past few months to follow a more contemplative practice. “I am not taking portraits right now, but I still document what I see—landscapes, still lifes,” Lacombe explained in an email.

Brigitte Lacombe, “California, Pacific #2,” (60×80 cm). Courtesy of Absolut Art. Lacombe is now offering four prints of her recent photographs for sale on Absolut Art, with proceeds benefiting Coalition for the Homeless. Though nearly devoid of human figures, the images are brought to life through the vivid textures of water, wood, and hair. Lacombe describes them as “taken from a distance, with a grainy quality, with a Blow-Up quality to them!” – a nod to the unnerving, unrelenting imagery of the 1966 Antonioni film. Lacombe’s views of the natural world provide a clear-eyed document of life in isolation, capturing both the feeling of distance and the sense of looking closer at our everyday surroundings and experience.

Brigitte Lacombe, “California, Pacific #1,” (60×80 cm). Courtesy of Absolut Art. With her studio in New York closed, Lacombe’s projects have been “on hold, postponed, or canceled.” However, she has continued to find sources of inspiration. “All around me and around the world so many people have done extraordinary, selfless, compassionate, and generous work,” Lacombe said.

“I am still thinking about” the long-term impact of the pandemic on her practice, she added. “Certainly less speedy, less greedy, less traveling, and more long-term projects, I hope.”

-

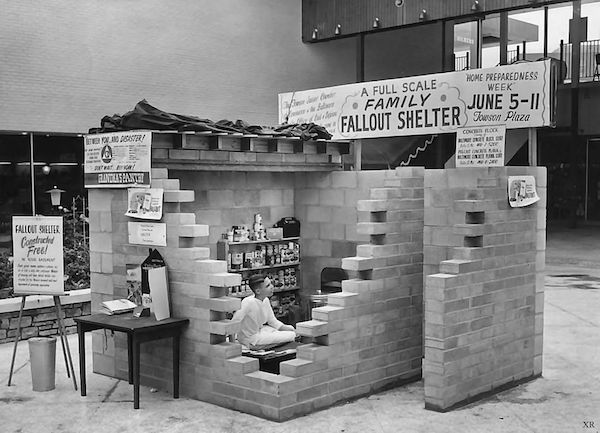

MORE REASONS TO STAY IN YOUR BUNKER

It looks like this may go on for a while. Even when arts venues reopen, capacity is going to face new limits. Photos of theaters in Germany where seats have been removed to accommodate social distancing, in some cases show theaters with 75% of the seats removed. Large scale operas require years of planning, and balancing of schedules. It may be years before live performances can be cajoled back into existence. As the sun sets on a recent golden age of high budget all-star live performance, it is lucky for us that many of these were recorded for posterity. With the idea that everybody is taking a financial hit right now, I’m focusing on the free stuff again. The one exception is a venue that is allowing people to rent (for less than the price of a latte) underground/independent films, with the proceeds going straight to the filmmakers.

Criterion Collection, Shirley Clark. Criterion has removed the paywall on their black film library during the month of June in honor of Black Lives Matter. They have some superlative titles including Body and Soul by Oscar Micheaux, Black Panthers by Agnes Varda, Daughters of the Dust by Julie Dash, Down in the Delta by Maya Angelou, and Portrait of Jason by Shirley Clark.

https://www.criterionchannel.com/browse

The Pearls for Cleopatra. OperaVision has posted loads of videos to their YouTube channel to watch for free.

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCBTlXPAfOx300RZfWNw8-qg

Among their most gonzo current offerings is The Pearls of Cleopatra, a Weimar era operetta that’s staged to look like a lost Charles Ludlum play.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z282rZtb_dI&t=749s

The Dutch National Opera and Ballet. The Dutch National Opera and Ballet has posted full ballets and operas on YouTube including a full Wagner ring cycle with English subtitles. For people seeking an unusual workout, they have ballet barre routines that you can practice along with at home.

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCW6ru0sy_mpgJ9boWJS59fg

Lincoln Center at home. The NYC Ballet is offering free streaming dance programs through July 17th. The programs will periodically change, so it’s worth keeping an eye on this site if you like dance.

http://lincolncenter.org/lincoln-center-at-home/series/dance-week

This is part of a larger program put on by Lincoln Center that includes a variety of other performing arts.

http://lincolncenter.org/lincoln-center-at-home

Film for Action. Films for Action (A Library for Changing the World) offers documentaries and inspirational videos for expanding your consciousness. They bill themselves as the largest learning library for social change online. With sections like The Economics of Happiness, Personal Change is Good, Collective Organizing is Better, The Invention of the White Race, and The Martin Luther King Jr You Don’t See on TV, this is an excellent resource for teachers planning a class on current events, or writers seeking topics to explore.

https://www.filmsforaction.org/

Lower East Side Biography. The Lower East Side Biography Project is the brainchild of Penny Arcade. The goal is to document some of the most interesting people who lived in New York from the latter part of the 20th century until the present day. Excerpts of many of those can be watched on their Vimeo channel for free.

https://vimeo.com/search?q=lower+east+side+biography+project

Google Art Museums. If you’ve been hearing about all of the world’s museums going online, but don’t know where to begin, Google has thoughtfully provided a guide, with links to the various museums.

https://artsandculture.google.com/partner

Filmmakers Coop donations. And for anybody with a few bucks to support independent filmmakers, Filmmakers Cooperative allows you to stream films from their catalog with proceeds going straight to the filmmakers.

-

QUARANTINE Q&A: Solimar Salas of MOLAA

Are you still changing exhibitions as you would if open and are the exhibitions virtual-only now? How’s that going?

We continue to have our exhibitions onsite and our new one, HERland, will open on August 22. Our online initiative through the MOLAA en Casa program allow us to open up our archives and bring back past exhibitions to share with our audiences while also giving us an amplified platform to share our current exhibitions and explore additional ways to interact with our visitors.Museums seem like a natural for social-distancing, i.e., museumgoers usually respect others’ personal space when viewing art and they aren’t allowed to touch anything. Is that being discussed as you begin to reopen?

Physical distancing in the galleries and the sculpture garden is something we have been constantly discussing. An exhibition’s layout is key as we consider physical distancing of the group that come, but there has always been that mutual respect the visitors display among each other to have enough space to enjoy their experiences with the art showcased. Right now there are guidelines we need to follow and we’ll be more vigilant during the free days we offer to the public.Does your staff work from home or do any staff members come into work? It would seem if everyone has their own offices, that that could be low-risk.

Some of our staff was able to work from home, while others worked onsite at the museum to ensure the safety and proper care of the artwork. Once the government allowed office spaces to reopen, we created a rotating schedule for the staff to keep density low while easing the team back to the workplace, with the proper precautions in place.How has the closure of your venue affected your museum budget? Did your institution put much stock in the admission fee? Did you have to furlough some staff and if so, will they be re-employed?

Early on during the pandemic, we restructured our budget, know that this situation would impact multiple revenue streams for us – admission, store sales, private event rentals, tours and workshops, among others. In April we had to furlough some staff, but applied for and received a PPP loan that enabled us to re-employ most or our staff early in May.Is there anything surprisingly positive you have noticed so far for the art world as we know it today? Or something you feel you or we all could learn from this?

Through technology, we have discovered new ways to communicate through this situation – how many of us have reconnected with friends from the past you hadn’t seen in years? As we look at new ways to communicate and support our communities, we have also had to rethink our traditional strategies, [like] getting outside our comfort zone to propel us. At MOLAA, to move forward to the next level of evolution. This is a catalytic moment for any organization as it looks towards the future, what it will be and how we stay relevant to our communities.Solimar Salas, Vice President of Museum Content & Programming

Museum of Latin American Art

628 Alamitos Ave, Long Beach, CA 90802

molaa.org -

Edwin Vasquez at MOAH

The sky is the source of light in Nature and it governs everything.

—John Constable

In the sky we had rediscovered the moving principle of any work of art: the light, and the motion of color.

—Sonia Delaunay

Edwin Vasquez installation view at MOAH Edwin Vasquez captures the colors of light in the night sky. His recent “Light Refractions” installation (in the “Light of Space” exhibition at the Lancaster Museum of Art & History [MOAH]) involves two hundred digital depictions of colorful abstract discs spinning, like planetary fantasies, through the infinite reaches of the universe. One is an earth-like green and blue orb wreathed by three red rings and crossed by a trilogy of small moons. Another is a glowing orange sun framed in concentric spheres of vegetal green, then molten crimson, then a final spiral of silver. Although created on a flat surface, the prismatic illumination is so intense, it seems to take on three dimensions.

Edwin Vasquez, “Collaboration” From a distance, Vasquez’ wall of two hundred global visions reads as a modernist grid. (Think of Joseph Albers situating spheres inside his honored squares. Or Frank Stella replacing his protractor curves with circles. Or Sol LeWitt adding bright colors to his repetitive geometry.) Yet Vasquez distinguishes himself from his famed predecessors through his use of new technologies (i.e., computers rather than the historically preferred paint on canvas) and his lavish infusion of intense pigment. This intensity turns the wall into a bejeweled mural or perhaps a postmodern digital mosaic. It shimmers. It sparkles. It points to the vast beauties of the natural world.

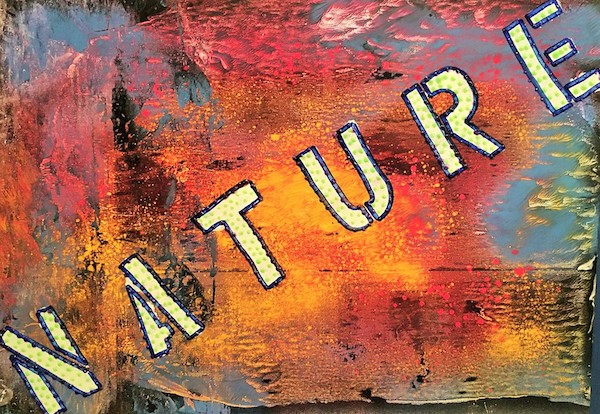

Edwin Vasquez, “Stop Racism” Born in Quetzaltenango, Vasquez immigrated to this country and settled, with his family, in the Antelope Valley. There he paints, experiments with new technologies, builds sculptures, and assembles multi-media compositions. He also curates and writes poetry. Vasquez has designed a billboard for a public art project. He attended the Kipaipai workshop in 2019. Currently, he is the artist in residence at MOAH during the 2020 census.

Edwin Vasquez billboard Immediately before installing his “Light Refractions” at MOAH, Vasquez participated in the “Collaborate & Create” exhibition curated by Andi Campognone at the Loft at Liz’s gallery in Los Angeles. Vasquez was paired with Jeanne Dunne. Together, the two artists made “The Birdhouse Where Nobody Lives,” a combination of painting and sculpture accompanied by a poem Vasquez wrote with Dunne’s assistance. The poem, which recalls hiking through the landscape after a devastating fire, begins:

Edwin Vasquez work Everything is charred on the mountain—

the once-perfectly arranged pine needle clusters

and the large pinecones scattered on the ground,

hopeless, decomposing, waiting for what is to come.

Those beautiful trees, once full of life,

were once giant clusters of jade green;

now they stand still with broken, charred branches,

fragile like wires stripped thin…

Edwin Vasquez, “Angel” Vasquez’ references to decomposing pinecones, charred branches, grey ash, and desolate hills, as well as the absent bird of the title, remind us of the recent wildfires here in California as well as the fires that were raging over Australia when the exhibition opened. The lament over the losses of nature’s gifts is a theme continued in other Vasquez works, such as his most recent small-scale works that pair painted image and stenciled text. The one with “NATURE” scrolled across it diagonally has depicts what appears to be a fiery wound. Environmental devastation cannot be denied. And yet, Vasquez’s work is never pessimistic. His radiant color and inventive compositions point to hope. To quote another American poet,

“Hope” is the thing with feathers –

That perches in the soul –

And sings the tunes without the word s-

And never stops – at all –

—Emily Dickinson

Hope is the bird who built Vasquez’s birdhouse. Hope is the art that lights the way.

-

SHELTER-IN-PLACE: Folded Fists

The words “origami” and “protest” are rarely used in the same sentence. In recent decades, origami has evolved from simply being a paper craft taught to children in a classroom to help them build their fine motor skills into a sophisticated art form practiced around the world. Although many origami artists still fold paper into birds, bugs and other figural sculptures, a few have created works bearing social and political messages. Most notably, South African/Swiss artist Sipho Mabona creates origami installations critiquing capitalism, global warming and animal cruelty, and Israeli artist Miri Golan’s works call for religious tolerance in the Middle East. However, political origami is still rare. This month, a powerful image of a Black Lives Matter fist folded out of black paper has been circulating on social media, confirming that origami too can be used to create powerful symbols of protest and change.

The model was folded by Beth Johnson, an American origami artist who lives in Ann Arbor, Michigan and has been designing her own origami models since around 2010. Over the last decade, she has developed a style that incorporates rhythmic, elegant – and sometimes whimsical – geometric patterning, such as her 2014 model Spirowl, an owl with two mirrored spirals representing the bird’s eyes (www.bethjohnsonorigami.com). She has gained a following in the global origami community for her models of sheep, jellyfish, squirrels, owls and bears and has been invited to teach her models at origami conventions in Japan, Korea, France, Germany, Spain, Italy, Scotland, Peru and Colombia.

Eager to contribute to the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States, Johnson decided to figure out how to fold a square sheet of paper into the shape of a fist raised in protest. “Mostly, I feel it’s important for me to listen right now and try to learn how I can do better,” admits Johnson. “But I still felt the need to express my support for the Black Lives Matter movement and to add my voice to the growing chorus of people across the country and around the world who are screaming, ‘Enough is enough!’”

Black Lives Matter Fists by various origami folders around the world, using Beth Johnson’s design, June 2020 She explains that the piece came together very quickly, in less than a day. On June 1, she posted it on Facebook and Instagram and the response was immediate and enthusiastic, with origami folders from near and far asking her to share the instructions. She posted them on her website, and in a week was showered with images from folders from around the world – the US, England, Peru, Japan, Brazil, Germany, Korea, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Indonesia and more – posting their versions of her origami fist in solidarity.

“It’s been great to have it so well received,” she shares. “Many people expressed interest in folding it and I immediately started working on some instructions. So now it has given others a way to express their support. And to see the messages – from all corners of the world – fills me with hope.”

Installation view, “Alle mænd er bøsser” (All men are gay) in the front display case, Psychopathia Sexualis, O – Overgaden. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Installation view, “Alle mænd er bøsser” (All men are gay) in the front display case, Psychopathia Sexualis, O – Overgaden. Photo: Anders Sune Berg Installation view, Psychopathia Sexualis, O – Overgaden. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Installation view, Psychopathia Sexualis, O – Overgaden. Photo: Anders Sune Berg