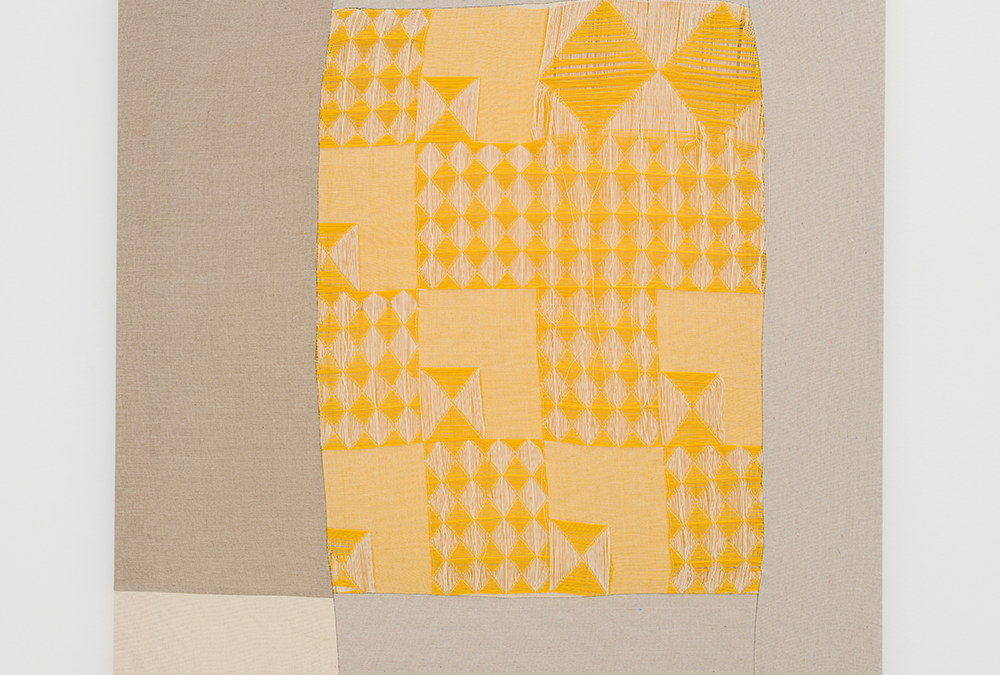

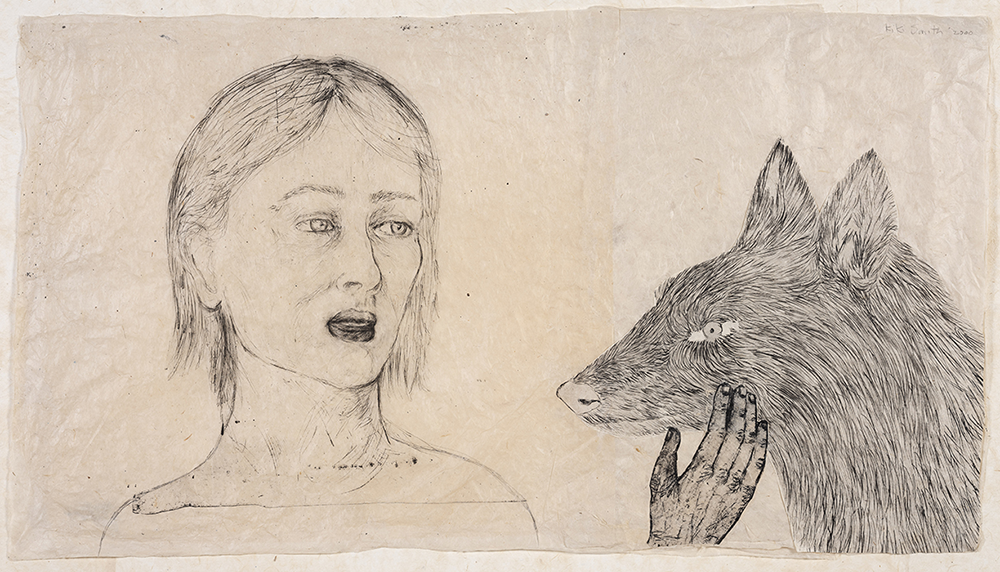

Congratulations to our winner Maureen Bond and our finalists, Maureen's photo is seen above and first in our photo gallery in the July/August 2022 online edition of Artillery. The following photographs are the finalists. Please see the info below on how to enter for...