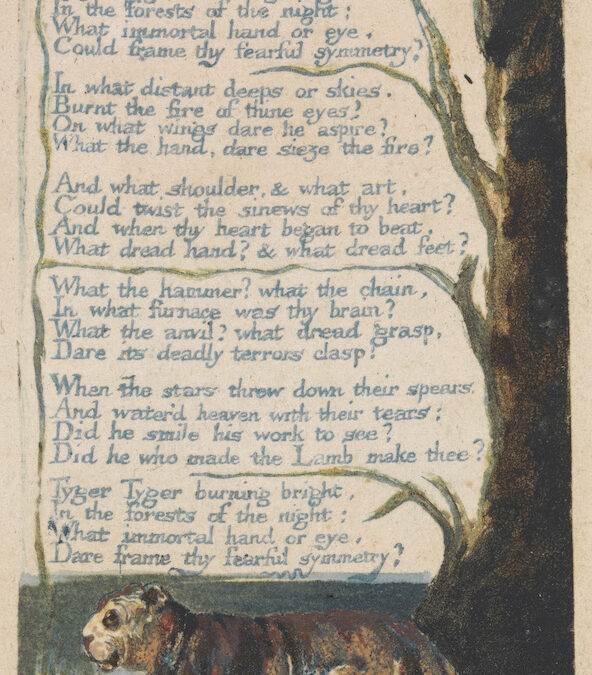

"And when we know the world, the world is ours.” —Bella Baxter What is it exactly that makes a being human?” Is it the presence of a human body or a human mind? Or is it some incommensurable, uncanny union between the two? For the philosopher Descartes, the answer was...