Your cart is currently empty!

Category: features

-

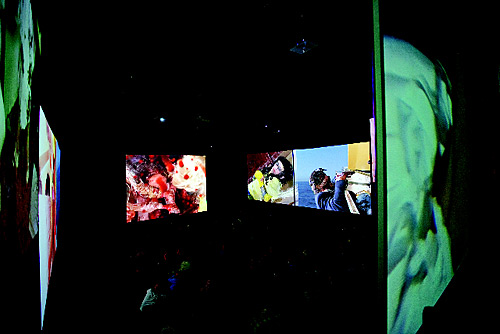

Let’s Go To The Movies

Pirates received its Los Angeles premiere at REDCAT recently: a visual and aural multi-screen feast/assault that covered all four walls of the theater. The audience, many of whom sat on the floor, were surrounded like the victims of the raid taking place onscreen(s). The only way out was through the exit door, which guilty-looking art lovers frequently resorted to, smiling awkwardly as they fled.Paul McCarthy, famed for his shit sculptures, chocolate butt plugs and other artistic inquiries that are lauded as forceful critiques of consumerism, has now plundered the pirate tradition in a style that is surely closer to the seafaring realities of yore than the Disneyland ride and movie franchise it cruelly parodies.As soon as the industrial-sized cans of Hershey’s chocolate syrup came crashing through the hatchway, the audience knew it was in for a McCarthy-style barrage of blood and shit on the high seas. Swollen-bellied, bulbous-nosed, giant-eared old salts squirted chocolate syrup from prosthetic phalluses, simulated masturbation with broom handles, sawed through noses and generally had a roaring good time. Blood was flying everywhere, pouring down the lens to a deafening soundtrack of drilling, screaming and obscene Yaaars and Aye-Ayes.

Upon any one of nine screens at any given moment one was greeted with such sights as a naked woman crawling around on a carpet in front of a ship-shaped bar, caressing herself with pained, imploring looks; a man with a freshly hacked-off leg being ridden by a droopy-nosed harpy in a blood-soaked scullery maid’s outfit; and the figure of the pegboy, famed in maritime lore, evoked by a sporty nautical gent in blazer and seaman’s cap who danced around a bottle of Morgan’s rum before frigging himself on a giant peg (the pegboy was a selected crew member who was obliged to keep his anus dilated in this fashion for the pleasure of his shipmates while on long voyages). Somewhere in there a parody of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? was apparently being played out, but it was impossible to keep up with all the references. The playfully tasteless mayhem continued for the standard theatrical 90 minutes, descending eventually into such popular piratical pursuits as cannibalism and torture (despite their cartoonishness, the bone-splintering amputation scenes were not for the squeamish).

It was fun to watch and it was obviously fun to make. To those of us unfortunates unable to draw upon an arsenal of critical theory in order to make the work appropriately rigorous, it was an old-fashioned bloodbath, an unabashed extension of the work of Herschell Gordon Lewis. This was cinema divested of such tiresome niceties as plot, character and dialogue, focusing exclusively on filth and gore, which, after all, is what most people go to the movies for. Visually stimulating, it therefore possessed value as entertainment. Only the crowd, strangely, did not seem entertained.

One would think that such a scathingly visceral overload might provoke some sort of reaction. But looking around the audience — whose expressions it was easy to gauge as everybody was obliged to continually twist and crane around in order to view the different screens — there was no laughter, no smiling. It looked like an uncomfortable experience for many, especially those who were on dates. Most people wore looks of tolerant amusement or puzzled seriousness. Resistant to the notion of mere entertainment, they seemed unsure of how they were supposed to react. They knew they were supposed to like it because it was supposed to be art, but appeared uncertain about whether many of the depicted acts could be morally sanctioned.

It seems a shame that a work of such crazed vitality should be the exclusive province of an audience that insists upon extracting or impressing meaning upon it, when the multiplex crowd would surely get a lot more pleasure out of it. The average moviegoer, quite forgivably, might fail to interpret the sordid merrymaking on view as a critique of the Hollywood dream factory and a metaphor for the U.S. invasion of Iraq. In years to come, Caribbean Pirates will probably serve as a worthy corollary to these times, but the only people who are likely to make that connection now are the chosen art house set, who made up their minds about Abu Ghraib long before McCarthy went to such excessive lengths to tell them what they already knew.

This is a work that lends itself generously to the possibilities of audience participation. It isn’t being marketed properly. Why not release it to a less discerning audience: one that would actually enjoy it? ■

-

Art Ceases to Desist

With today’s digital era so rich in explicit displays of virtually every aspect of the human experience — including amateur exhibitions of bodily functions beamed to us live via webcam — the idea of museum exhibits raising hell in America may seem, well, passé?

But a generation ago a handful of works by artists Robert Mapplethorpe and Andres Serrano ignited a national pissing match (if you will) over art, its public funding and, ostensibly, freedom of speech.

Of course, the volume of societal dialog on public art exhibitions and taxpayers’ financing controversial works had been escalating long before the visions of Mapplethorpe and Serrano were hung on the proverbial gallery wall, but it was those two artists who were at Ground Zero when simmering cultural tensions exploded into a volatile debate.

Looking at it now, Serrano’s 1987 Piss Christ seems an odd selection for what was then denounced as the apex of petty vulgarity fraudulently pawned off as “art” by a bored bourgeoisie looking for a cheap thrill on the taxpayer’s tab. The photograph delivers its punch not through the sublimely beautiful image of a radiant crucifix bathed in warm hues of amber, but rather lands a haymaker through the title of the work itself—and what it reveals.

Those two words — Piss Christ — turned a richly divine image into something the mob saw as starkly demonic. Yet reverse the words and televangelists would be selling it.

But it wasn’t until two years later, in May of 1989, that Serrano’s urine really hit the fan. Seizing on the fact that the National Endowment for the Arts had indirectly awarded Serrano a $15,000 grant, New York Senator Alfonse D’Amato saw a golden (so to speak) opportunity to grandstand on publicly funded “filth” and took to the Senate floor to tear up Piss Christ both figuratively and literally. D’Amato’s esteemed colleague from North Carolina, Sen. Jesse Helms (think Strother Martin’s character in Cool Hand Luke), who had been agitating for a brawl with the NEA and its damn Yankee liberal supporters, jumped in with his buddy Al.

“The Senator from New York is absolutely correct in his indignation and in his description of the blasphemy of the so-called artwork,” Helms said. “I do not know Mr. Andres Serrano, and I hope I never meet him. Because he is not an artist, he is a jerk.”

Helms’ view of Mapplethorpe was decidedly more ominous both in tone and implication, with the astute senator alerting the New York Times that the artist was “an acknowledged homosexual.” If Serrano’s work rocked conventional perceptions of the Judeo-Christian boat, Helms undoubtedly saw Mapplethorpe’s unconventional perspective on bullwhips and black men as the wall hangings from the seventh ring of hell.

And Jesse wasn’t alone. Mapplethorpe’s work resulted in protests and criminal busts in Cincinnati, where city fathers charged the Contemporary Art Center and its director, Dennis Barrie, with obscenity and a jury of mid-Westerners delivered an acquittal.

Those were some big headlines two decades ago. But if the argument has faded, its legacy has not. “The culture wars of the late 1980s and early 1990s changed the very structure of arts funding in ways that now often go unremarked or unnoticed,” says Richard Meyer, an associate professor of art history at USC who has written extensively on the subject. “Individual artists are no longer eligible, for example, for funding from the NEA and virtually no one expects—or applies to—the federal government to support dissident, controversial or otherwise oppositional art.” Meyer says the result has been a withering away of the “artistic culture of social dissent,” erosion he calls “a genuine loss and a great shame.”

Perhaps. But in hindsight it’s hard to shake a sense of uniquely American frivolity that surrounded some of the proceedings, indulging our super-sized taste with an over-dramatized battle between freedom and censorship.

The fact is that even angry grandstanders like Helms and D’Amato publicly acknowledged the fundamental right of Serrano and Mapplethorpe to make and display their art. Consider that in comparison to the artists in the Netherlands today, who need round-the-clock protection (provided by the government) for having dared to offend Islamic sensibilities. The very credible threats against these artists’ lives today puts the rants of the Jesse & Al Show, and even the lame busts, in stark perspective.

And Serrano’s back with a new show—entitled simply Shit and featuring yet more of the artist’s, um, excretions—that opened at the Yvon Lambert Gallery in Chelsea in September. As Artillery went to press, there’s no word yet of any senators denouncing him from that chamber.

But I suspect if the exhibit’s patrons listen carefully as they line up to appreciate the oversize photographic servings of feces, they may well hear the chuckling drawl of the ghost of a good ol’ boy reminding them, “You get what you pay for.”

That goes for the government as well as the art. ■

-

Kerry James Marshall

This article originally appeared in our November/December 2008 issue on Everyday Politics:

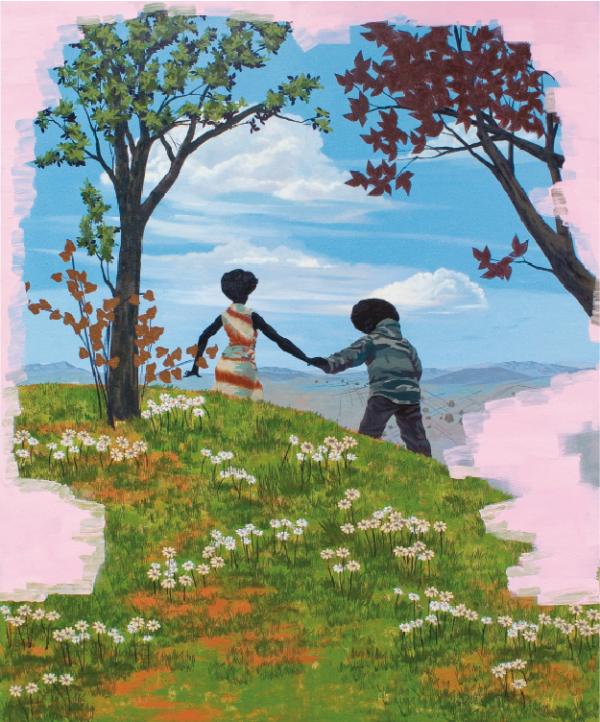

Nov/Dec 2008 Artillery cover. In a text written for this show and displayed on one of the gallery walls, Kerry James Marshall says “I am working on paintings that address the theme of LOVE.” “Love” is less a theme than a pretext for Marshall’s real subject, which is history. There is nothing of the “idyll” in any of these paintings — and “wistful” is not a word that can be easily attached to their calculated bits of romantic fancy. At the risk of sounding either latently racist or completely loony, as I was looking at the paintings, a line from an old Sondheim show tune ran through my head: “Liaisons – what’s happened to them?”

Like the undercurrent of disillusionment and desperation that runs just beneath the flirtation and frolic of the Bergman/Sondheim vehicle, there is a kind of sadness and not a little anger beneath these “Rococo” motives (e.g., a woman’s body sinuously stretched out in the grass of a clearing — singly or in a couple; a couple hiking or chasing over a dune or hilltop) that, today, are a stock of kitsch imagery. Marshall alludes to the kitsch in the more schematic passages of his “pastoral” settings (fields and bluffs of grasses and wildflowers). Marshall conveys a kind of impatience through abstraction — or obliteration — for his own apparent pseudo-nostalgia. The landscapes aren’t lost in the miasma of gossamer fabrics and the rosy filtered light of wooded parkland or sunsets, but deliberately whittled away at the edges, brushed out in broad, flat pink strokes. This is about historical revisionism and displacement; also, simply power.

Africans or (African-French) don’t begin to appear in French painting until approximately the early 19th century. They appear somewhat earlier in Italian and Spanish painting in the late Renaissance. So what? How many Africans were there in France at the time? And just how many Africans made it to the European royal courts — where these paintings took their inspiration — anyway? Inspiration might be overstating it. The kind of pastoral fantasy worked by Fragonard, Watteau and Boucher was exactly that. It was sheerly escapist fare even for the aristocracy for whom it was intended. The vast majority of white provincial French people were similarly closed off from this world.

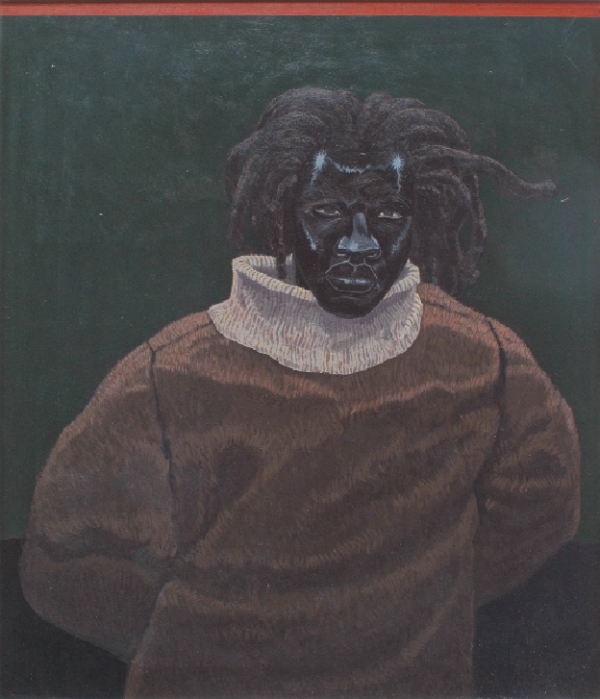

Kerry James Marshall, Portrait of John Punch (Angry Black May 1646), 2008. Even before we view Marshall’s “love” pastorales, though, we have a sense of this confrontation with Eurocentric ideals of beauty or nobility in a series of portraits hanging in the front gallery. They’re formal portraits of beautiful people. One, a proud, somber, distinctly African and very black face sporting a thick mane of dreads, in a sable-colored sweater has a lion’s bearing that has nothing to do with the over-sized cowl neck of his sweater. African or not, this could be the mien of an Elizabethan lord — or conceivably an urban intellectual from anywhere.

Directly across from this portrait is another, somewhat angrier, lordly black man, this one swagged in gold chains — much as he would have been had he been painted by, say, Titian. Titian never painted a black aristocrat, but he might have if there were any to be found in Venice.

Marshall is doing more here than simply confronting European notions and traditions, though. He’s claiming them for his own — which, as for any late 20th- to 21st-century American artist, they are. But is there really a point to photoshopping (in painterly fashion) black people in or “pink-washing” the fantasy out? It’s as if Marshall wants a rewrite of art history. Africans are noticeably absent from European painting until well into the 19th century — an implacable historical fact that is pointless to argue with.

Marshall’s portraits are undeniably beautiful; but the most interesting work here by far are the comic panels in the last gallery from Marshall’s “RHYTHM MASTR” series — a very contemporary order of cultural and historical confrontation — where past and present collide in the kind of gritty, multi-cultural, polyglot urban tide pools ubiquitous in cities like Los Angeles. In one panel, a voodoo idol or ceremonial figure is seemingly conjured by a contemporary figure in the foreground with a bongo drum. In another, titled Ho’s Stroll, the sense of anywhere/everywhere is explicit: “What is this place?” A cloud of Asian characters issue from a van, while the protagonist takes on the 20th century: “If Lincoln supposta freed our asses in 1865, why the fuck was we gittin our heads cracked tryin to vote, in 1965?” This is where it gets interesting: at the divide (or not) between cultural and political disenfranchisement. Why do I have the feeling we’ll be asking similar questions this year in states like Ohio and Florida?

Kerry James Marshall: PORTRAITS, PIN-UPS And Wistful Romantic Idylls, Exhibition Dates: September 6- October 24, 2008, at Koplin Del Rio, Culver City, CA. Images courtesy Koplin Del Rio Gallery, Culver Ctiy, CA

-

First Lady Love

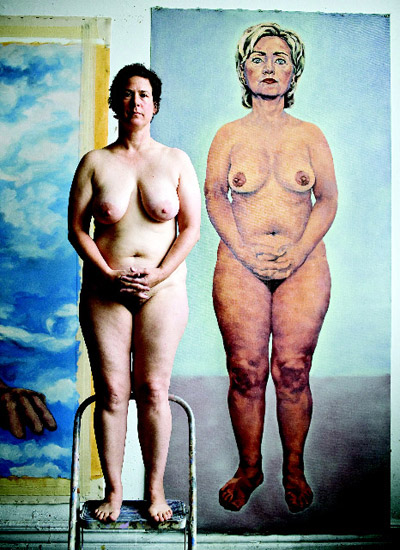

It all started with a dream. “I was in a small library, and she opened the door. She put her file folders down and pinned me to the wall, kissing me,” recalls painter Sarah Ferguson. “She was so, so forthright. I found it very refreshing.”

The woman in the dream was Hillary Clinton. From that day in 2007 forward, the former presidential candidate has been the primary focus of Ferguson’s work. In addition to oil portraits, Ferguson has also created numerous photo collages, some of which can be seen on her website and in a self-published book, Hillary and I. Her obsession with the politician seems one part feminist, three parts erotic.

“Hillary is portrayed in the media as cold and calculated, but I see her as sexual,” states Ferguson unequivocally, and she’s on a mission to get others to recognize Hillary’s sensuous side. “When I read Maureen Dowd, the Hillary she concocted in her head was so different than the one in my head. In a 100 years, people might look back at Dowd’s writing and form an idea of what Hillary was like. With these paintings, I’m trying to document my viewpoint.”

In Ferguson’s East Village studio, Hillarys abound. There’s a close-up of a pissed-off looking Hillary titled “Pink Hillary,” the first of the series. “I love the expression. Those eyes! She’s so sensitive, so prickly!” Ferguson coos. A portrait of Hillary pondering a lizard shows the viewer a softer, more private side of the public figure. Yet another canvas places Ferguson in the foreground, sitting in a chair with a microphone between her legs, while Hill looks on from the background, microphone held horizontally in both hands. Ferguson painted that one shortly after the Democratic Convention. “I’m holding the microphone in my lap, away from my mouth, because my voice has been denied.”

Among these many moods of Hillary, an eight-foot-tall portrait stands out. Hillary’s face is molded in a familiar expression — lips tight, chin slightly raised, her demeanor serious and authoritative. To her detractors, this “don’t fuck with me, fellas” look might epitomize what they dislike about her. The twist here is she’s buck naked, staring you down as if to say, “What are you looking at?” Her aging flesh and sagging breasts are painted in loving detail. “I could have made her more erotic, but this is the beauty of the real. There’s no artifice. She’s stripped bare,” Ferguson explains.

Photo by Rainer Hosch On Christmas Day 2007, she posted an image of Naked Hillary on Flickr.com. “I was so involved in political blogging, and I wanted to talk about things that weren’t being discussed, like the sexism [that Hillary provoked]. Within a week, I had 500 hits.” Things continued at that pace until Flickr tagged the image at the end of February. But Ferguson was happy with the results of her experiment. “The only way to find it was by typing ‘hillary naked’ in the search, so at that moment, there were a lot of people who wanted to see Hillary naked! I really tapped into something.”

Until about six years ago, Ferguson, 43, was pursuing a career as a math professor. But shortly after she was awarded tenure at Wayne State University in Detroit, Ferguson asked for a leave of absence and moved to New York in 2002 to paint full time. She enrolled in an MFA program at the School of Visual Arts in 2006, and graduated this past spring. “Both math and painting are a search for truth, and both are a battle. I would end up with a big pile of scratch paper, trying to figure out a formula, and I must have painted over Naked Hillary five times, trying to get it right.”

Interestingly, Ferguson had one of her biggest breakthroughs working on a 7′ x 8′ canvas entitled Hardball, that depicts Chris Matthews and Keith Olbermann jerking each other off. “Since I don’t care about them like I do Hillary, I was free to make mistakes.” The violet blue tones of the canvas make it clear that the couple is watching television. “Porn?” I ask. “No, they’re watching Hillary!” Ferguson replies. Silly me.

With Hillary’s bid fading into history, Ferguson intends to continue painting her muse. In her most recent work, Ferguson put Hillary’s head on a doll’s body. “It’s a little surreal. There’s some detachment. It’s less personal. A dealer who looked at my previous work said most artists don’t work from complete identification. But I had to go through that living with her, talking to her, having her as an imaginary friend.” Ferguson sees this new Hillary as a universal mother to us all. “She’s looking down and her head is like the size of your mother’s head when you were getting your ass wiped. It’s like she is there to take care and provide and clean things up. And the heavens are there, and the sky. It’s death and rebirth. I think her role as senator will be much larger now,” says Ferguson, with a hopeful, lusty glint in her eye. ■

-

No Beauty, No Truth

Mike Kelley’s first feature length movie takes place mainly at a high school. Cheery bright classrooms are full of 30-year-old sloppy students. Auditoriums stage assemblies with campy musicals and pageants. Gleaming lockers line the polished hallways. It’s a regular Sadie Hawkins Day, where white trash meets Goth.

The opening credits roll against the backdrop of a bleached out sunset over the ocean, with hues of moldy greens and dried-blood reds. An over-the-top symphonic soundtrack accompanies this endless sequence of soap opera sunsets until finally the film’s title Day is Done appears. Next, a harsh juxtaposition of hundreds of slimy earthworms wriggling and slithering to raw psychedelic mind-blowing noise. Then an average-looking high school with your not-so-average student faculty. So far so good, looks and feels like Mike Kelley. Keep it up.

A trio of ballerinas with white painted faces and black leotards dance through the empty hallways. A train whistle blasts from the intercom announcing a change of pace. Vampires and creepy bad-skinned adults make up the school staff who go about their busy day xeroxing and talking on phones and making no eye contact. And no one is aware that everyone is severely fucked up.

This is probably the first 10 minutes of the film. The audience has been laughing the whole time. I had a grin glued on my face. Day is Done is practically a feel-good movie. It’s easy to identify Kelley’s influences in this film, yet his own vision as writer and director comes through loud and clear. His casting, costumes, music and nonsensical plots comprise his signature sensibility. His characters embody every hippie, yippie, punk rocker and performance artist he’s ever encountered, who in turn project Kelley’s own mischief, horror, bad taste, sexploitation, perversion, religion and ugliness. Is it just a coincidence the film’s subtitle is “Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstructions #2-#32”? No, of course it’s not a coincidence, neither are his film references. Kelley’s having a ball with Day is Done; it’s practically a self-parody, and incidentally a kick-ass soundtrack he and Scott Benzel collaborate on.

Mouvement Portfolio #1 (Picking a Mary), 2005 Everyone agrees that Mike Kelley is a major American artist whose influence has had an impact on younger artists today. His films can’t boast the same claim, however. That’s not to say his films or videos suck. But I have to say, his filmmaking doesn’t measure up to his art making. His art stands alone as original, whereas his films have whiffs of Waters, Lynch, Meyer, Warhol, Craven and others. Kelley’s art borrows thematic elements, but his films borrow stylistically.

Day is Done practically rips off Waters. For instance, the way he uses children in the film. Pure unabashed exploitation. Waters was famous for this, as of course was W. C. Fields. Other scenes are right out of Pink Flamingos and Kelley is actually able to pull it off (which must make Waters green with envy nowadays). Like Waters, Kelley draws on real experiences. Day is Done’s premise is taken literally from a high school yearbook — particularly the quotes and captions that go with the school photos. You know, the ones you or I never had next to our picture: “Second place Prom Queen,” “Member of the Speech Club,” “Captain of the volleyball team.” I would guess Kelley never did either. Like Waters, Kelley doesn’t have to go far for his inspiration. He finds it in his own backyard.

They say truth is stranger than fiction. What about when it’s exaggerated and exploited? So is it even truth then? I wondered about that, and about what sets Kelley’s Day is Done apart from John Waters. I thought about how void of beauty nearly all of Kelley’s work are. He’s the artist responsible for turning “warm and fuzzy” into germ-infested bombs. Then I thought about that Keats line, “Beauty is truth.” It seems weird that I would think of truth and beauty when there was absolutely neither present in Day is Done. Both are conspicuous by their absence. It would seem more fitting if I thought about filth and lies.

Maybe Kelley doesn’t see beauty in truth. Some things are ugly and it could be that truth is one of them. War is ugly and certainly true. But it’s not truth. So therefore it’s not beauty. Kelley’s work is deep-rooted, and probably stems from the truth, but he never finds beauty in it the way, say, Larry Clark does. Kelley’s preoccupation with high school and the deeply troubled period of adolescence might represent a genuinely negative experience in high school, similar to Clark’s own obsession with adolescence. But Kelley adds a layer of irony, with his faux fascination and adoration of these “normal” people from the high school yearbook, and all their extracurricular activities. So maybe it’s not truth after all. Maybe it’s even envy. These are the jocks, the squares, the goody-two shoes, who may have fascinated, but most likely repelled the likes of Kelley and other outsiders. To him, normal people were the freaks, like Marilyn in The Munsters. And admittedly, it’s hard to imagine Mike Kelley as a high school student.

But don’t worry. There’s really no reason to ponder, pontificate, deconstruct or intellectually wank off to Kelley’s Day is Done. You can just sit and laugh. The film certainly has merit and I think everyone should go see it, especially if you like comedies. But don’t expect a plot, don’t expect much sense, and don’t expect beauty.

Photos by Fredrik Nilsen; courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery

-

Catherine Opie

California is known as the land of fruits and nuts. And it’s true, we’ve got wacky environmentalists, kooky lefty liberals and fruity homosexuals. And artist Catherine Opie actually fits all three categories, sans the loaded adjectives. Nothing wacky about Cathy, and nothing kooky about her politics, and certainly nothing fruity about her sexuality. But why does California attract such a rambunctious group of people? I’m hoping Ms. Opie can give me some answers.

I recently had the opportunity to sit down with Opie, who was just back from Santa Fe, New Mexico, where she was the only Los Angeles artist selected to be in the SITE Biennial. There she showed her new series of children’s portraits. And portraiture is what she’s famous for. But I was more interested to talk about her survey show at the Orange County Museum of Art, where Opie’s work is more about California.

Catherine Opie, Untitled #1 from “Freeway” series, 1994 When I arrived at her house in the historic West Adams district of central Los Angeles, I experienced a slight sense of deja vu. I had just seen her OCMA show “In and Around Home,” and many of the photographs in the exhibit were taken, well, at her home, which she shares with her partner and their two children and many pets. Her dwelling was very comfortable and welcoming. A short wooden picket fence opened into a front yard filled with big shade trees and children’s toys, complete with an anti-Bush banner hanging on the cool breezy porch. Constant activity was going on when I was greeted by the artist and a very friendly Doberman: a housekeeper was running the vacuum in the living room and in the kitchen workers were fixing the plumbing. Opie was very gracious, offering me something to drink, but then we quickly got down to business, as she had to take the plumber to the local hardware store for a part.

One thing is for sure, she’s very proud of her show in Orange County, which brings together many elements of her work she’s been addressing for almost 20 years now, and two new series of photographs never exhibited before here in So. Cal. When I mistakenly referred to it as a retrospective, she reminded me, “I’m still young!” At 45, her baby-face features and boyish thick mop of brunette hair (not a single grey!), reveal an artist very comfortable with herself and her art. She clarified for me, “It’s a very specific show in regards to my ideas around community and landscape as well as Southern California. A lot of people always think of me around the portraits, and never really go beyond that even though that’s only a quarter of my work. But it always goes back to that, that I made this body of work in the early ’90s.” She goes on to explain how the portrait series actually were “a little bit off what I normally make.” And that’s what makes the Orange County show distinctive, the exclusion of her portraits, which were an extension of the theme community, but more specifically, her own milieu and particularly during the AIDS crisis in the homosexual world.

Catherine Opie, Miggi & Ilene, Los Angeles, California, 1995 As Opie was talking about all this, it occurred to me that I had not ever looked beyond the surface of her photos in that way. I never really considered her work as political. For example, her famous freeway photos are gorgeous to look at with their careful composition, wonderful light and abstract quality. But they’re also about destruction, and ultimately, political. And sure, I knew her portraits were political in the subculture kind of way; even dysfunctional families can be considered a political topic. But her politics go beyond that. Opie is concerned about the bigger picture. And living in California fostered a lot of that thinking.

In that sense, Opie’s show at OCMA brings the photographer full circle. Although she’s not a native, (she moved out from Ohio at age 13) she grew up in Orange County. And “In and Around Home” documents her life and neighborhood in central Los Angeles. But the show starts in Valencia, with her MFA show at CalArts, where her first concerns with the raping of landscape were documented. Tenderly shooing her Doby away for the umpteenth time, she mused, “What disturbs me more is the use of landscape in California. When I moved from Ohio in the early ’70s, we grew up surrounded by acres of cornfields. And I got to grow up surrounded by beautiful landscape. Orange County was still orange groves. When we moved to California, we moved to this burgeoning Master Plan community called Poway Rancho Bernardo. So I watched from my backyard all of this development happen. And it used to be vineyards and rocks that I climbed on, and sage and chaparral, and I’m really interested in nature. I really like nature as a person. I mean, we have chickens!”

Catherine Opie, Abandoned TV It so happens, “Master Plan” became the title of her thesis show. Most artists would be hesitant to include their college work in a mid-career survey, but OCMA curator Elizabeth Armstrong insisted on including “Master Plan,” when Opie mildly suggested it and dusted off the negatives.

“Master Plan,” is a body of work that chronicles a tract-housing project under construction in Valencia where Opie was attending school from 1986-88. The work is very conceptual and some of the photographs are not her strongest work when viewed individually. But as an installation, it holds its own, and is not even dated in the least. Her message and what Opie is trying to communicate still rings true today. “For me it was going beyond the image, and really talking more about people’s choices in terms how they create community and also the white flight from the urban environment. I came from the suburbs. I was a suburban country club kid. Why do these environments exist? Why do people have rules and regulations within these environments? What do they serve? And really trying to explore that.”

Most of the photos in “Master Plan” are rather banal and flat. For instance the photograph of the Troidal family, who were interviewed and became part of the project, reads like a straight studio portrait, nothing particularly special. The family’s kitschy décor became still life photographs. At first glance, it appears Opie might be mocking the people who go for that style of living, surrounding themselves with bad taste so bad, even John Waters would not find it terribly interesting. When I suggested this, she set me straight immediately. “I was interested in not just [taking pictures of] it, but why people made those choices.” I did however get Opie to agree that living in a gated community would be a cookie-cutter hell of offensive blandness. “Yeah, there’s a little bit of imaging it that way, like, wow, how tacky and horrible these are and I’m glad I don’t choose to live in that kind of environment.” But ultimately she is more concerned about the drastic alterations to the landscape that such a mainstream lifestyle requires. She elaborates, “Part of the problem is the fact that the resources that it takes to maintain these developments is completely unprecedented in relationship to what California can do in providing water and energy. So what bothers me most about these communities is that they’re not approached from some kind of sustainability. That’s what bothers me the most, is watching this major acreage go, but every single house in Palmdale at this point, the technology has, that they can include solar, that goes into the grid. So you don’t have Stage 3 Alerts anymore! So these housing developments are only doing it to profit from it. But it has nothing about giving back to California as a state, or the notion of nature.”

Catherine Opie, Troidal Family, 1986-88 Fortunately for Opie, she has an ocean breeze coming through her Craftsman-style home, because I don’t know if she could handle the guilt if she had to use air-conditioning, (LA was experiencing a heat wave at the time.) It was refreshing to hear an artist talk about topics like environment, community and politics. Artists are typically known for their self-indulgence, but Opie couldn’t be further from this stereotype. And her art works beautifully with her politics. Take for instance her Surfer photographs. A whole room is dedicated to that series at OCMA, and you can practically feel the ocean mist and smell the sea salt when surrounded by the large scale works. This series doesn’t seem to fit with the others in the exhibit, but after hearing Opie’s manifesto, its inclusion is necessary. Opie is about California, and we can’t just skip the beaches and that community.

So is California to blame for spawning liberal environ-mentalists? This beautiful terrain replete with mountains, deserts, forests and beaches — that’s what California is, and when residents see the stripping and destruction of this wondrous land, they get upset. Next thing you know, you’re a concerned citizen. What happened to our clean air? Our beaches we used to be able to swim in?

You wonder how so many people can simply not care. You’d have to maybe live in a . . . gated community? Or maybe sheltered in your safe ritzy millionaire home? Another series of photographs called “Houses” are included in the OCMA show, which are of Beverly Hills mansion facades. Why are they in the exhibit, and why did Opie bother to take the photos? Are both of these communities about comfort and apathy? Opie’s work is not didactic and it doesn’t make value judgments either. And that ambiguity is what makes all her work very accessible.

Catherine Opie, Untitled #27 from “Freeway” series, 1994 “In and Around Home” was first shown at The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Connecticut. But when it traveled to OCMA, both Opie and co-curator Elizabeth Armstrong agreed to expand the exhibition. In part because the space was much larger, hence the decision to include other works that would further expand on that particular theme, which is clearly California, hence the surfer photos, the mini-malls and the freeway ramps. The exhibition is divided into the different series displayed in their own spaces, for the most part. So when working your way through the show, a certain sense of where Opie’s coming from really comes to light.

The only body of work that seemed out of place with the theme was “1999,” where Opie set out on a cross-country road trip to create a series of photographs that would “represent the idea of Americana, in relationship to people’s fear of Y2K.” But in hindsight, Opie added, “Now that 9/11 happened, Y2K looks very foolish, in terms of fear. . . The fear that gets whipped-up within our culture is just mind-boggling to me.” Although the photographs are some of the strongest work in the show, they’re not California, and perhaps they relate when Opie leaves California. Opie does have that natural talent when looking through the camera lens. Her photos harken to the greats such as Walker Evans and Ansel Adams, and perhaps those two come to mind with her appreciation for nature and environment.

The “1999” photographs come before the last room, which is “In and Around Home.” And now we’re back home. Opie’s nearly twenty years of work does give a glimpse into the artist’s life and work, if one can ever separate the two. And don’t forget, that’s not all of Opie’s work. If you add the ’90s portraits and her most recent children’s portraits, then perhaps we’d get the whole picture. Her portraits may be what everyone thinks of when they think of Opie, and they may be the showier work, but they’re not her story. And the arc is what you get at OCMA. But one story Opie told me about growing up in Ohio actually might be the most revealing. “We spent most of the time swimming in the polluted lake,” she laughs. “When I grew up, the lake was on fire. They’ve cleaned up Lake Erie quite a bit, but it was highly problematic when I was a kid.” Then Opie mocked a little girl’s voice talking to her mommy. “Mom, why are all the fish dead?” She then lowered her voice, “Because they died of old age.” Perhaps Opie bought her mother’s euphemistic explanation as a kid, but she’s not buying it now.

“In and Around Home” at OCMA ends Sept. 3, 2006. “American Cities” at Gladstone Gallery in New York runs from Sept. 9 — Oct. 4, 2006