Your cart is currently empty!

Category: features

-

LAURA LONDON

Laura London often channels celebrities through her photography, but not necessarily in ways that you’d expect. She doesn’t document musicians, models or actors onstage or off, or portray them in surreal situations like say, Annie Liebovitz does. Instead, she asks teens and young adults she knows to perform for the camera. By photographing them preening and vamping as an exploration of idealized identity, London’s images become about the nature of culturally indoctrinated emulation.

Laura London, Rock Star Moment 2, 2000, Courtesy Laura London In one of her images from “Rock Star Moment,” a series from 2000, a teen faces the camera with attitude, a guitar hung at her waist. Decked out in baby-doll dress and platinum wig, with black nail polish and smeary lipstick, the girl passes as a juvenile version of Courtney Love. In another picture the girl is dressed in black, leaning over a bathroom sink. Her mirrored reflection reveals a face masked with dark eyeliner and blood-red lipstick, her expression feigning Trent Reznor’s creepy living-dead look. Those two photographs suggest how London approaches her young subjects; that collaboration is a necessary component, even if it is left ambiguous as to whose imagination (the photographer’s or the model’s) is really being tapped.

“Once Upon a Time… ” is London’s most recent and ambitious series, begun in 2007 and periodically updated. Like her earlier work, it involves collaboration with young actors and a reliance on imagination. But the concept for the series was sparked by memories from a real situation. Rose, the charismatic singer of Guns N’ Roses, was a neighbor of London’s in 1990. One only had to stand in line at the supermarket to know about his on-and-off relationship with his then-wife, Erin Everly. Rose was often in the news for volatile behavior, and word in the neighborhood was that he argued with his wife and painted graffiti on their garage door. London took a photo of the garage door and Garage Text, 2010, is the result. (The spray-paint scrawl even referenced “Sweet Child O’ Mine,” a famous GNR song he wrote, inspired by Everly.)

London never intended to publish anything from the roll of film she shot that day, and put it away. About two decades later, it became the catalyst for this new body of work. Most pictures from the series are invented scenes, for which she hired a crew to help: actors, a makeup artist, and an artist to paint the many fake tattoos. Whether a male or female model stands in as “Axl,” he/she becomes the androgynous sex symbol Rose was in his youth: slim and muscular, with long blond hair, pale skin, pouty lips and mournful eyes. Often, the actor is dressed in a sleeveless white T-shirt to show off tattooed arms, and of course the trademark red bandanna across the forehead.

Laura London, Once Upon A Time 6, 2010, Courtesy Laura London In Once Upon A Time 6 (2010) London’s model actually posed across the street from Everly’s house, in front of the bushes where rumor held that Rose had thrown his wife’s wedding ring. Neighbors told London they saw him later in the same spot with a metal detector. In the photograph, the actor is wearing a long black coat embellished with colorful embroidery, heavy boots, a black hat, and long blond wig, his face obscured from view. The image resembles a fashion shot, but is infused with reference to an anecdotal occurrence. It is neither pure fact nor exclusively fiction.

In Once Upon A Time 1 (2009) London’s nephew projects a calm and in-control performer, charismatic and sexy. He’s a pretty boy with a bad-boy aura, his arms covered in tattoos of girls and crosses, dressed in a Mickey Mouse T-shirt and bandanna as head-scarf. The nephew has the young Axl’s delicate complexion, but not the buff physique, which adds a level of humor. So do the painted-on eyebrows and tattoos and the actor’s melodramatic expression. In other photographs, “Axl” poses with “Erin.” In True Love Tattoo (2010) “Erin” stands alone with her bare back to the viewer. Her long, wavy, honey-brown hair is seductively wrapped around her neck to reveal a tattoo with roses, birds, hearts and the message “true love.” (Rose’s real-life relationships were tumultuous, with legal accusations of assault and battery from not just Everly, but Rose’s subsequent main squeeze, supermodel Stephanie Seymour.)

Once Upon A Time 5, 2009, Courtesy Laura London “Axl” comes with an entourage of not just ex-girlfriends but ex-bandmates. Another of London’s nephews poses as guitarist Slash, in a wig of long black curly hair and a Jack Daniels Whiskey T-shirt. He looks fey, with makeup and jewelry, in spite of the signature top hat, sunglasses, tattoos and heavy boots. In still more pictures, some black and white rather than color, “Axl” and “Slash” are joined by other members of GNR’s original lineup, circa the celebrated 1987 album Appetite for Destruction. The models’ performed demeanors add an air of all-out ridiculousness in the vein of This is Spinal Tap.

Laura London, Once Upon A Time 9, 2009, Courtesy Laura London In Once Upon A Time 9 (2010) a bare-chested and jean-clad “Axl” looks like a drag queen in a disheveled wig, with heavy painted eyebrows and pink lips. He hugs himself and feigns angst. Another example of gender-bending as a comedic play on androgyny is London’s inspiration to have a female model pose as the protagonist. London’s young intern becomes “Portrait 1” and two images—one of her in cowboy boots on a carpet and the other looking like the real-life young woman she is, seated on a stool—seem a perfect pair to convey the contrast between reality and acting and play it for humor.

The melodrama that London’s models project as deadpan and earnest brings to mind reality TV. Think of The Osbournes. And if you consider that the deliberate blurring of fact and fiction may be our updated version of the long tradition of documentary photography, reality TV is a good parallel. London’s photographs are about the nature of “seeing” in our now over-exposed society. With a 24/7 media environment dominating real life, truth and fiction become fused—an ironic condition for a medium that traditionally kept those realms separate.

Laura London, Salon Style Wall 2, Group Portrait 2, 2000, Courtesy Laura London. -

THE POETS HOUSE

A quivering grid of afternoon sunlight shifts across the polished hardwood floor of a long narrow room. But for the drowsy hum of the air conditioner, all is silence and stillness, an ambience ideally conducive to the reception and refinement of clear thought. Immersed in scholarly retreat, an owlish old man with a malodorous rucksack occupies an armchair. Students stretch out on sofas; others sit at desks that border the room, pecking at laptops or scribbling in notebooks. A display of books by the greats—Milton, Herbert, Dickinson, Eliot—line the window ledges like poetic ramparts against the world outside, where crowds flock Battery Park and ferries traverse the glittering Hudson toward the skyline of Jersey City beyond.

It is unusual to find this many people (today, at least 10) gathered in silent contemplation of the written word. The Poets House is not a library—books can only be perused on-site —but it is laid out like one, and unlike most libraries nowadays, which often seem more like video arcades or children’s playgrounds, this one has only one public computer on the premises, for accessing the data base—strictly no Internet use, as I found out when rebuked by an intern for browsing a horse-racing site. The Poets House, naturally, houses only poetry, that most ignored and impractical of the arts: more than 50,000 volumes of it, and growing.

It is difficult to get the news from poems, yet men die miserably every day for lack of what is found there.

—William Carlos WilliamsWith weighty biographies and critical studies thrown in, Blake, Whitman, Stevens and other prolific heavy-hitters take up one or two shelves on their own. Less predictably—with Kleist above and Koch below—the works of Bill Knott occupy almost an entire row, the black lettering on many of the thick white spines shamelessly flaunting the Lulu imprint. The open-door policy results in a preponderance of self-published books. Aisles of obscurity, shelves of neglect, florilegiums of futility, all meticulously alphabetized: a repository of poets who thought their thoughts worth recording, their words worth sharing.

“So many had sacrificed themselves for art without even their names surviving. On the other hand, what mattered most was that all who had given themselves to their work had their real reward in having actualized themselves.” Easy enough for John Berryman to say, considering his place in the pantheon, but perhaps not particularly comforting to poets whose efforts at self-actualization have never advanced beyond open mic nights in empty coffee houses and years on end of polite rejection from little magazines that almost nobody reads.I open the Collected Poems of Tim Dlugos at a random page: “Attacked by people I admire/as a poseur, or knave, or liar/perceived as dry, or shrill, or bored/or (worst of all) roundly ignored.” Which seems to sum up the poet’s lot. Resentment or indifference are the usual reward for crafting felicitous lines, and—it goes without saying—a complete lack of remuneration that is accepted as an essential and unavoidable element of the poetic occupation.

As any unknown poet will tell you, modern poetry is a nepotistic arena in which success is entirely dependent upon who you know. There is no “supply meets demand” dynamic such as exists with music and art, where middlemen are perpetually scurrying around in order to satisfy the appetites of an ever-increasing audience hungry for whatever’s thrown at them. Because there isn’t much of an audience, it follows that there is no universally recognized criterion of quality, so it’s easy to perpetuate a closed-world incestuousness determined by critical and academic preciosity. Modern poetry, like modern art, is often prized according to its obscurity (to produce work that is direct and accessible is to render it inaccessible to critics: it leaves them with nothing to do and could put them out of business if allowed to flourish), and innocent readers sometimes wonder why it needs to be interpreted rather than experienced.

I, too, dislike it: Reading it, however, with a perfect contempt for it, one discovers in it, after all, a place for the genuine.

—Marianne MooreThe musing silence is occasionally broken by a book cart wheeling along the floor or the tapping of footsteps as a librarian walks by, smiling graciously at the visitors. On a neighboring sofa, a woman with dark, soulful eyes smiles mysteriously to herself. I try to read the title of the book that has provoked such a seductive reaction but it’s concealed by the back of her luminously-veined hand.

The spines of many of these volumes bespeak sad lives dedicated to a difficult and often masochistic pursuit. An original volume of Frank Stanford’s Crib Death published by Lost Roads and signed by C.D. Wright—with whom Stanford had an affair that precipitated his suicide—has a sacred, haunting quality. As does much of his work: the title of one poem, “Death on a Cool Evening,” is richly resonant in light of his chosen end.

Further along, the fecundity of the Ts is noticeable—more tragic poets—in particular, the Thomases: Dylan, Edward and R.S. Then there’s Francis Thompson, author of “The Hound of Heaven,” while strangely conspicuous by its absence is James Thomson’s “City of Dreadful Night.” Presumably it hasn’t been donated yet.

Poetry is language. And nowadays language isn’t greatly valued as a form of communication. In which respect the Poets House is a last redoubt, closed off from the city’s tumult: a place where the old verities are upheld, where poetry feels important and words can breathe.

Language is free. Take generously.

Poets House, 10 River Terrace, New York, NY 10282, 212.431.7920, ext. 2818, www.poetshouse.org

Perusing the library, Photo Courtesy of Mark Woods.

-

Prizes and Politics

Nights CAN BE long in Moscow. But come spring, as the light fades ever more slowly, the evenings get off to a late start. Which may be why I inadvertently kept a driver waiting on the evening of April 3rd to ferry me and another journalist to the sprawling Artplay Design Center in the Kurskaya district of Moscow for the Seventh Annual Innovation Prize award ceremonies. In lieu of the press preview of Prize nominees which had begun while I was still en route, the two of us had taken a leisurely stroll around the Arbat neighborhood, where we were staying, and visited the from-the-ground-up replica Cathedral of Christ the Redeemer—as much a symbol of Russian redemption from Stalinism as religious resurgence.

Artplay, one of several industrial facilities in Moscow to be reconfigured into an “art cluster,” is an exhibition facility fit for a megalopolis. On a multiple–football field–length expanse of its mezzanine level is what seems like half the Moscow art world, along with a phalanx of media from Russian outlets to Bloomberg, the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times.

One of the first people I’m introduced to is a gaunt, cerebral-looking gentleman, who turns out to be Alexander Brodsky. His “Cisterna” has been nominated for (and ends up winning) the Innovation Prize for Best Work of Visual Art. But the moment is almost completely lost on me, his identity blurred in the cacophony of the moment, as I try to distinguish him from the Alexander Borovsky (of the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg), who’s one of the jurors, and Alexander Gronsky, a photographer who’s been nominated for the Innovation “New Generation” Prize. It’s not for two or three days, not long after I’ve seen the documentation for the dramatic “Cisterna” installation, that I finally realize Brodsky may be one of the few contemporary Russian artists I’ve encountered off Russian soil. His work has not only been exhibited in New York (and elsewhere) since the 1990s; he actually lived in New York between 1996 and 1999 and was included in the Guggenheim’s huge “Russia!” survey of 2005.

For the moment, though, there are curators, collectors, museum officials, gallery directors, other media folks and a smattering of the award nominees who I’m trying (in vain) to correlate to the categories they’re nominated in. Standing like a beacon in this scrum is the Innovation Prize director, Christina Steinbrecher, resplendent in a long acid-chartreuse dress, whose success as the director of Moscow’s Central House of Artists and art director of the ArtMoscow fair, and more specifically, in negotiating the divergent political currents in the Russian art world generally, doubtless played into her appointment to the position. Politics have played no small role in both major Russian art prizes—the Kandinsky, sponsored by the ArtChronika Cultural Foundation, the philanthropic arm of ArtChronika, Russia’s dominant art publication; and the Innovation Prizes, sponsored by the National Center for Contemporary Art, which maintains branches in St. Petersburg and the Urals as well as Moscow.

If there was any thought that the state-supported NCCA might be reticent to unleash the politically unorthodox, the 2005 debut of the Innovation Prizes put that fear to rest. Both the Kandinsky and Innovation Prizes have gone to politically controversial nominees. The 2008 Kandinsky Prize winner, Aleksey Belyaev-Gintovt, was critically assailed for the neo-Stalinist aesthetic of his plainly nationalistic “Daughter Russia.” Last year’s Innovation Prize for the Best Work of Visual Art went to the firebrand art collective Voina (War) for one of its most spectacular protest gestures—a 65-meter length graffiti phallus painted on the underside of a drawbridge that crossed directly to the St. Petersburg headquarters of the FSB (formerly, KGB). One of the collective members, Alexei Plutser-Sarno publicly scorned the nomination as a co-optation—all of a piece with the controversy that swirls around these contests. A cursory scan of response by nominees and winners of these prizes makes it clear that biting the hands that feed us is the default posture for the artist who suffers to be recognized.

Alexander Brodsky’s “Cisterna,” 2011, which won the Innovation Prize for Best Work of Visual Art. Still, it was hard to escape the sense that Innovation’s nominating committee had taken a step back from political outrage. In a conversation not long before the jury convened to decide upon the final awards, Steinbrecher herself took note of the public ambivalence and conflicting attitudes that colored the political backdrop.

In the meantime, another art (or, as self-described, “feminist punk/rock”) street performance collective, Pussy Riot, was responding to this ambivalence in its chosen fashion—with a guerilla performance staged in that aforementioned symbol of resurgent and conflicting Russian aspirations, the Church of Christ the Redeemer, provoking the two-fold wrath of Moscow’s law enforcement and the Orthodox Patriarch of Moscow. Three members of the band were detained and still jailed on the evening of the Innovation awards. (They remain in jail—an international cause célèbre.)

The elaborately staged Innovation Awards were televised with the Aidan Gallery’s own Aidan Salakhova and Moscow publisher Philipp Dzaydko hosting the telecast. Only days later I learned that Salakhova would be closing her gallery in the Winzavod gallery complex to focus on her own studio practice, which seemed to fit a certain economic/behavioral pattern in the evolving Moscow art world. Open big (preferably in a landmark industrial space), close quietly/suddenly, and reappear as something else, maybe even somewhere else.

Winzavod is not very far from Artplay, but seems worlds apart from its retro-futurist aspect. Winzavod is a vast 19th-century winery transformed into a complex of gallery/exhibition, performance and studio spaces, architectural and design offices, including an attractive café and retail space. But the approach from the Kursky train station retains a certain grittiness—traversing a motley assemblage of fast food joints and novelty hawkers, and finally an underpass that features amazing graffiti. Depending upon what’s being exhibited at the galleries, the street art, some of it in all probability by Moscow’s most famous street artist, Misha Most, may be the highlight of the excursion. Although Elena Panteleeva, Winzavod’s director, wasn’t specific about gallery comings and goings, it was clear by the time I left Moscow that the commercial gallery rentals at Winzavod were just half of what they had been only two years earlier.

Winzavod’s nominee for Innovation’s hotly contested “New Generation” award (co-sponsored by the Stella Art Foundation) had been Valery Chtak, an artist represented by the complex’s Paperworks Gallery.

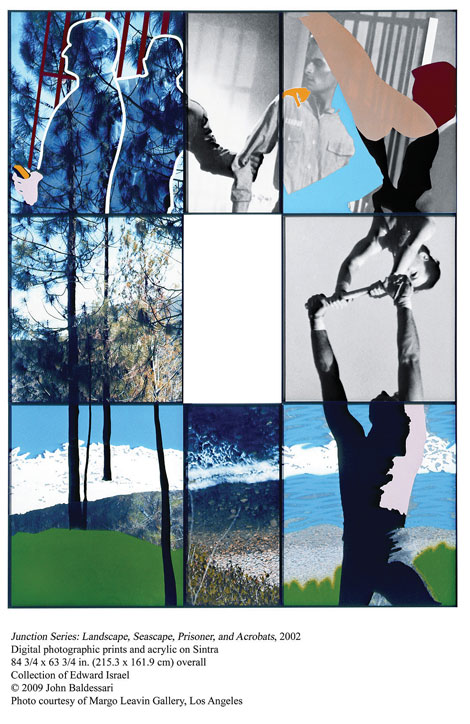

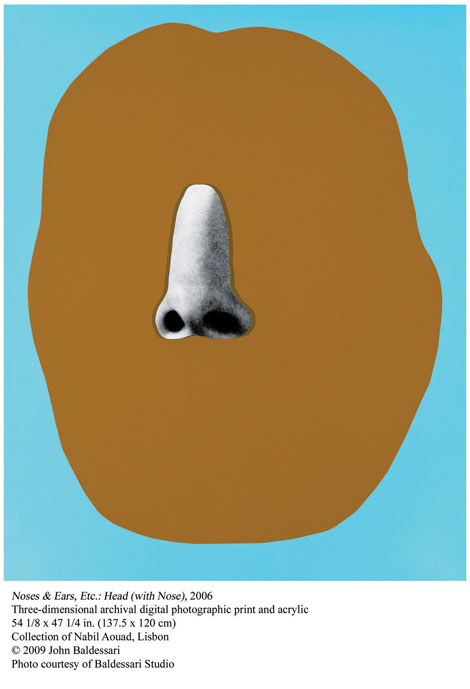

But when the smoke cleared we learned that the award would go to Louise Brooks–bobbed Taus Makhacheva, for her video installation, “The Fast and the Furious.” (Alexander Gronsky took home a special British Council award for his photographic series, “Pastoral.”)Makhacheva’s work might be called conceptual—but “The Fast and the Furious” is also very personal. It took Makhacheva back to her family’s ancestral roots in Dagestan, a semi-autonomous region of the Caucasus with a distinctly macho (and car) culture, and involved a bit of performance on the artist’s part. A week later, Makhacheva opened another, even more controversial, multi-channel video installation drawing on the aggressive alpha-male culture of Dagestan—this one documenting dog fights and their participants in tandem with documentary footage of a freestyle wrestling champion—at the Paperworks Gallery.

Upon entering the discreet quarters of the Stella Art Foundation one could be forgiven for hearing echoes of that open-close rhythm of Moscow’s commercial art world. Its gallery was featuring an exhibition of painted fans by Andrei Fillipov, that opened and closed explosively as painted light fixtures went on and off directly behind them. Unlike many “oligarchettes” who have pursued their art collecting ambitions abroad—among the blue-chip international brands at auctions in London and New York—Stella Kesaeva has kept her focus on Russia.

Which is not to say that Kesaeva has entirely ignored the international art world. When I sit down to chat with Nikolai Molok, the Stella Foundation’s development director, I do so in full view of a large portrait of Kesaeva by Alex Katz, with a Damien Hirst dot painting on the opposite wall and a Koons balloon dog off to one side. Molok emphasized that the core mission of the Stella Foundation was to support the Moscow Conceptualists. Beyond that, the foundation sought out artists from every region, including the former Soviet republics, to showcase on and off the foundation premises.

Anatoly Osmolovsky’s “Bread” series, 2012 The ever-expanding scope of the Stella Foundation’s activities would lead one to believe that it would soon outgrow its quiet location; and indeed Kesaeva and her foundation have ambitions for a full-blown contemporary art museum—a joint public-private venture to be housed in a former bus garage designed by Konstantin Melnikov—not to be confused with the Garage complex (designed by the same architect) Moscow-London-LA art-fashion oligarchette Dasha Zhukova recently closed, and reportedly intends to reopen.

If it seemed to some that the Innovation ceremony wrapped anticlimactically, it probably had less to do with the nominees’ distance from political gesture or controversy than a sense that a good deal of the recognition memorialized by the awards—especially Brodsky’s— was overdue. A special award was given to Zurab Tsereteli, a sculptor and philanthropist, “for the support of Russian contemporary art.” Not until later that week would I learn what an understatement that was.

I did not see Brodsky or Tsereteli at the sumptuous after-party, but it seemed as if every other important Moscow museum or cultural commissar was there, from the NCCA’s Mikhail Mindlin, who had appointed Steinbrecher to oversee the Innovation awards, to Olga Sviblova, the prodigiously energetic founding director of Moscow’s Multimedia Art Museum.

“It’s said that she never sleeps,” painter, curator, writer and critic Maria Naimushina, says to me the following week, in husband Oleg Tyrkin’s studio, not far from the Petrovka branch of the Museum of Modern Art. Judging from the extent of her museum activities—with the Moscow Photography Biennale in full swing, MMAM shows filled both its Arbat flagship and the Central Exhibition Hall Manege near the Kremlin—it seemed entirely conceivable. At the Central Exhibition Hall, I encountered another expert—Matthew Stephenson, then director of Christie’s Russia. Although Stephenson’s role frequently involved connecting Moscow’s collectors with the international “brand” names that dominate the auction markets in London and New York, not unlike Kesaeva’s advisors, he is broadly informed on virtually the entire scope of collecting activities in Moscow and elsewhere in Russia, including Russian artists of almost every practice and degree of prominence—and many of the anonymous “Nonconformists” who preceded them.

It came as no surprise to later discover that Stephenson had a small but choice collection of Russian artists. Unlike Brodsky, Komar, Kabakov, et al., their names were unfamiliar to me. But their significance, even brilliance, was immediately manifest. It would be hard not to be struck by, for example, one of Vitaly Pushnitsky’s lightboxes of the early 2000s. They have a Cornell quality about them crossed with something equal parts Starn Twins and Jack Goldstein. Or Olga Chernysheva’s “On Duty” series of 2007. Is it remotely possible to regard anyone as “faceless” after looking at these photographs? Issues of materiality and fungibility are interwoven with the spiritual and sacral in Kandinsky Prize–winner Anatoly Osmolovsky’s “Bread” series.

Although Osmolovsky and a number of his peers have achieved some degree of local, national and even international recognition, there are scores who remain unknown. Hence the top-down push by the commissars of the public and private spheres to find, encourage, reward and sustain the best, most innovative talent. Yet connecting the talent, innovation and ideas with an audience of informed enthusiasts, collectors, and the culture at large remains challenging, particularly in economically challenged conditions.

Spotting Zurab Tsereteli’s son, Wassily, in a restaurant at the Petrovka branch of Museum of Modern Art—the museum his father founded and funded—Naimushina seemed to imply that Tsereteli’s ever expansive and relentless social networking might be usefully applied to a communications and distribution system that frequently ignores the middle- class “aspirational” collector that needs to be drawn into Russia’s evolving art market. Connecting a distracted and disconnected public with an avant-garde associated with places like Winzavod might be difficult when “99% come from yards like that.”

“How do you identify who the innovators are, who is truly innovative, among a small circle of emerging artists,” Stephenson asked rhetorically. “But there were a lot of young, up-and-coming artists there [at the Innovation awards ceremony]. It gives them something to aim for. Everyone connected with the art world was there: the NCCA, the stakeholders, media artists, aspirational collectors, people in business. The owners of these new businesses want to be seen. It’s a new element in society.”

This was something you could see people coming to grips with in Moscow—both in the art and on the street: the redefinition of a society and its aspirations. Scarred by war and starved for three generations, Russian artists who could once scarcely breathe their aspirations for fear of censure seem to want to inhale the sky. Yet juxtaposed with the immensity of this ambition is the Moscow still reclaiming, rehabilitating and renovating its past. It has taken a generation to move past a degree of cynicism and mistrust that would have once constrained (if not crushed) such scope and ambition. While distanced from current political controversy, Brodsky’s award for “Cisterna” seemed an appropriate summation, invoking the “invisible cities” contained within the “Big City”—the imaginary, aspirational city that precedes and succeeds the built city absorbing it all; and portending a new “Silver Age” the aspirational Moscow may yet seize beyond its long nights.

-

Nothing to Buy

Documenta 13More than 30 venues—166 international artists within a few square miles—a forum for ideas rather than conspicuous consumption: it’s Documenta 13! Held every five years in Kassel, Germany, and founded in 1955 by Arnold Bode, an art professor and designer from Kassel, this is the world’s most important and enduring contemporary art show. Depending on the curatorial vision of the exhibition organizer(s) that shape the content, you might encounter a scolding, pedantic treatise on colonialism, or a Teutonic, oppressively intellectual “march-of-death” experience. Thanks to American-born artistic director Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, this iteration of Documenta was accessible to nearly anyone with interest in the larger world around us, and provided conceptually rich art while also feeding the senses. The overarching theme of the mega-exhibition was “bearing witness,” with all that the phrase implies.

Museum Fridericianum, 2012, Museum Fridericianum, 2012, photo by Nils Klinger © dOCUMENTA (13) Don’t get me wrong: I love art fairs and revel in such market-driven events. But after the parties and the bright shiny happy pretty things, Documenta was the perfect antidote. Where else in the world could you see, under the same roof, one-quarter of all the ancient carved-stone “Bactrian Princesses” known to exist in the world, then go to debate the relationship between art and philosophy in a closed seminar? The exquisite Earth Goddess-like sculptures from Central Asia date back to the 2nd millennium B.C. and were borrowed from a private collection; the seminar was German philosopher Christoph Menke’s “What is Thinking? Or a Taste That Hates Itself,” held on Tuesdays from 11–1 p.m. in one of the galleries at the Fridericianum museum, the main Documenta venue. This brings a saying to mind: the French eat; the Italians make love; and the Germans think.

Among the most memorable projects was Chicago-based artist Michael Rakowitz’s installation, featuring shards from the destroyed Buddhas of Bamiyan (“All we are breaking are stones”); the burnt remains of books ravaged when the Fridericianum was bombed by the Allies in 1941, and deemed too unimportant to restore; as well as beautiful stone books symbolizing the lost volumes carved by contemporary Afghani carvers using stones quarried at Bamiyan. The emotional impact of this powerful installation was that of a body blow, as our complicity in the destruction of cultural treasures crept into conscience like a bad memory. The title of Rakowitz’s installation (What dust will rise from one horseman?) was taken from an Afghan proverb on cooperation.

Michael Rakowitz, “What Dust Will Rise?,” 2012, Commissioned and produced by Documenta 13 with the support of Dena Foundation for Contemporary Art, Paris, and Lombard Freid Projects, New York, courtesy the artist; Dena Foundation for Contemporary Art, Paris; Lombard Freid Projects, New York, photo by Roman März. At the Neue Galerie Kassel, Sanja Ivekovic’s “The Disobedient (The Revolutionaries),” 2012, was a stand-out. The Croatian artist assembled plush toy donkeys of all eras, shapes and sizes, and displayed them in a glass case, capturing the attention of hordes of German schoolchildren touring through the galleries. (Note to self: art education is alive and well in Europe!) The piece provided a great example of an artwork that is cute on the surface but has a dark underbelly: adults were absorbed by the text on the opposite wall, describing the political protestors and martyrs symbolized by each cute lil’ stuffed animal, from Anna Mae Aquash to Primo Levi—a broad international assortment of political protestors who died because they were stubborn—like donkeys are reputed to be.

Canadian artists Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller’s wonderful sound installation “Forest (for a thousand years)” featured a recording of a choral piece sung by the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir, set in a glade deep in the recesses of the landscaped Karlsaue Park. Speakers were hung in the trees surrounding the tree-trunk stool seating arranged in the center of the clearing, and if you found your way there through the mud, your reward was 25 minutes of transcendent, blissful listening to a composition by Estonian composer Arvo Pärt. Cardiff and Miller had another site-specific installation at Documenta, in Kassel’s Hauptbahnhof train station. The “Alter Bahnhof Video Walk” used augmented reality to guide audiences on an engaging walk through the station. After borrowing an iPod from an office inside the station, you were told to take a seat on a bench and wait. As you held the media player in front of you, Cardiff guided you on a walking tour through the station as various video and audio vignettes unfurled. You proceeded as directed, often wheeling around since the recorded events were both mundane and convincingly realistic—people running to catch trains, a dog barking, a baby crying. At one point, Cardiff guided viewers to one of the train platforms, the same platform where Nazis loaded victims onto cars bound for the concentration camps. At another point, Cardiff stopped the narration and “turned off” the video at the request of a mysterious man who preferred to remain incognito.

The tour ended with a duet dance performance, a wonderful chance encounter made all the more powerful by Cardiff and Miller’s playful manipulation of temporality. At Documenta 13 there was nothing to buy—just pure experience to remind you what contemporary art can be.

-

THE ROAD TO DOCUMENTA

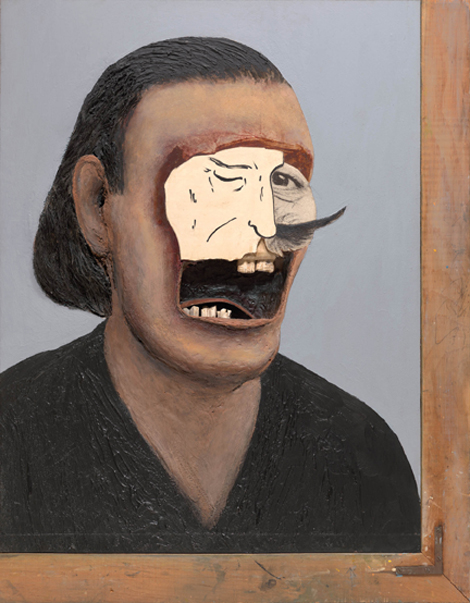

I’ve been warned that Llyn Foulkes is preparing furiously for “Documenta 13” and as I get in touch to arrange a meeting, I’m wary, in part, due to his reputation for fractious soliloquies regarding fellow artists, critics, art magazines, and in general, the art world cliques that hold him at arm’s length. By his own account, Foulkes has been an outsider, a talented iconoclast shunned by the powers that anoint the grand artists of the day. Foulkes’ auto-scribed narrative is the continuous subtext for his meandering commentary on the art world, a surging tide of cynicism and discontent which is incongruously and entirely enmeshed with Foulkes’ innocence, and even naivety and idealism. These qualities mix in an uneasy boil beneath the surfaces of his eye-popping, sometimes disorienting tableaux, which are fueled by his encompassing world view and his obsession with politics, money, power, and his negotiation with culture in a broad sense. Foulkes’ work incorporates material derived from his personal life to the extent that figures and vignettes that loosely represent his lurking presence populate his paintings. He cannot help but put himself into his work. His vision reflects a deep suspicion of power and a sense of alienation: the individual alone, standing outside of society, editorializing on and defying the conventional wisdom.

Despite declaring himself the odd man out, this is Foulkes’ moment. Although he has shown regularly in Los Angeles since the early 1960s and has had many moments over the years, he has never been in the spotlight as much as he is now. His inclusion in the 2009 Hammer Museum show “Nine Lives: Visionary Artists From L.A.,” in his view, set him up for the Venice Biennale last year, and “Documenta 13” this year. And in 2013, Foulkes will have a retrospective at the Hammer Museum.

Llyn Foulkes, Installation view from Nine Lives: Visionary Artists from L.A., March 8 – May 31, 2009, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. Photo: Joshua White. When I meet with Foulkes at his studio, I find him engaging and charming. He is entirely open and hungry for conversation. Given his reputation, and our somewhat uneasy initial phone contact, I am a bit surprised. Embarking on a freewheeling discussion, we sit down at his workbench. “What do you want to see?” he asks. Then, “See this?” He directs my attention to a small construction on the wall behind me. It is about 4-x-4 foot by my estimation, and as I take it in, the image begins to register to me: A woman is curled up on a bed, cradling a shiny egg-shaped object. Foulkes’ double, his pictorial incarnation, sits in bed next to her reading the paper. The funky surfaces of fabric and carpet, and Foulkes’ manipulations of space play tricks on my eyes, and the whole thing seems to quiver. Foulkes started The Awakening when he began to feel his marriage was over, and it is a painting that enjoys legendary status. It is the same piece he pulled from a show at Patricia Faure Gallery in the mid-’90s after it was up for only a week because Foulkes said, “It wasn’t done.” This is what he has been laboring over for “Documenta 13,” the 18-year painting, or thereabouts, but now it is less than half its original size. Foulkes also showed The Awakening in “Nine Lives: Visionary Artists From L.A.” at the Hammer in 2009. In the exhibition essay, Hammer curator Ali Subotnick wrote that Foulkes felt pressure to capitalize on the success generated by his work in the 1992 MOCA exhibit, “Helter Skelter: LA Art in the 1990s.” He responded to the pressure by exhibiting a painting that wasn’t resolved.

Foulkes still isn’t done with the piece. He begins to explain some of the changes he has made recently, describing how each choice creates a cascading effect, before he finally gives up in resignation, saying, “All these decisions are being made very quickly, at the end. There was a thing here before,” he indicates a place on the painting, “and you know… ah, I don’t want to get into it.”

“This painting started at nine feet. It was nine feet.” Foulkes slows his voice, drawing out the word nine. “This painting is now just this big.” And he gestures with his hands to indicate the shrinkage. “I told Documenta I would finish it,” he laughs, somewhat ruefully, “and then I started changing everything.”

Up close, I notice the eyes are Phillips head screws; the flat surface reflects light. The tapered body of the screw recedes into the intricately formed eye sockets of the figures. The screw heads cast a small shadow and create remarkable depth. Reflecting on what I had read about this piece, I comment on what I expect are fictional elements in this narrative, and Foulkes answers without hesitation, “The whole thing is fiction.” Then he shifts immediately into a discussion about engineering the piece, talking about all the changes he still needs to make. “What I’ve been trying to do for a long time,” he continues, “is to make a really dimensional painting. You never see it done so much with anything that has figures in it; it is usually done in abstract. You take a shape and you say, ‘this is bending this way; I have to curve this, that way.’ And it keeps changing.” Foulkes wants very much to be done with it, to put it, and what it represents, behind him—yet he can’t seem to let it go.

Llyn Foulkes, Dali and Me, 2006, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles Foulkes pours the kind of detailed craftsmanship into his work that some might consider the result of obsessive or stultifying perfectionism. He comments on the importance of keeping his hand in his work, saying, “I believe very much in process, because I believe that you really grow in process.” Rather than hiring assistants, he needs to contend with the work himself. “It’s easy to have somebody else make it for you,” he explains. “You change things, and things happen, and you discover things.”

Then, as though all the talk of changing his painting has made him tired, he declares, “But my machine, I don’t have to worry about that. You’ve seen the machine before?” I assure him that I have and recount the first time I saw him perform. We step into the “Church of Art,” the space adjacent to his studio where he performs. The machine, a self-contained hybrid instrument, a one-man band with drums, percussion, horns, and a bass guitar string that Foulkes plays with his feet, is lit with spots and amplified with microphones plugged into a PA system.

Foulkes tells me he’s packing the whole thing up and shipping it to Germany for “Documenta 13,” where he’ll be performing. He points out that although he’s driven it to San Francisco and all over Southern California in his van, he’s never shipped it anywhere, and that makes him nervous. “At first, I wanted to go on the cargo plane,” he says. “I wanted to be the escort so if it went down, I would go down with it. I could never recreate it!”

He has taken off his shoes and slid onto the seat, getting ready to play. I ask if the various horns and bells came from salvage yards. “They’ve been from salvage places, some were from Cost Plus.” He hits a bell lightly with his mallet and it rings with a warm sound that brightens up the space. We continue talking as Foulkes breaks into fragments of songs to expand on his answers. He seems lightened and relatively untroubled as he works the machine and sings. Clearly he enjoys this, and I wonder aloud if he feels free of his inner critic when he is playing. “I have an inner critical voice with the machine,” he responds, “it better be damn good. When it’s really rolling along, I feel every part of my body is in tune.”

Llyn Foulkes live at Church Of Art, photo by Iva Hladis ©2008 Toward the end of our conversation I note that he has expressed disappointment in various interviews over the amount of recognition he has received. I ask how much is enough. It is rhetorical, and perhaps unfair, but I ask anyway. “How much is enough?” he repeats. “Yeah, I know,” he reflects, “I do have that problem. You see, it all comes from when I was a child.” He begins playing again, building into a song. “When I was a baby, my Daddy left me; he said, ‘I’m going down to California, with a banjo on my knee.’ So I made my daddies up – from the picture shows, from the face that grows from the picture shows…” Foulkes explains that as a child he felt the only way he would be loved was to be famous. “I’ve never gotten over it. As much as I try, I still haven’t gotten over it. So you say, ‘How much is enough?’ I don’t know.”

Coming soon: “Llyn Foulkes: A Retrospective,” February 3–May 19, 2013, at the Hammer Museum, for more info: hammer.ucla.edu

Below: Llyn Foulkes, The Lost

Frontier,1997–2005, courtesy Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. -

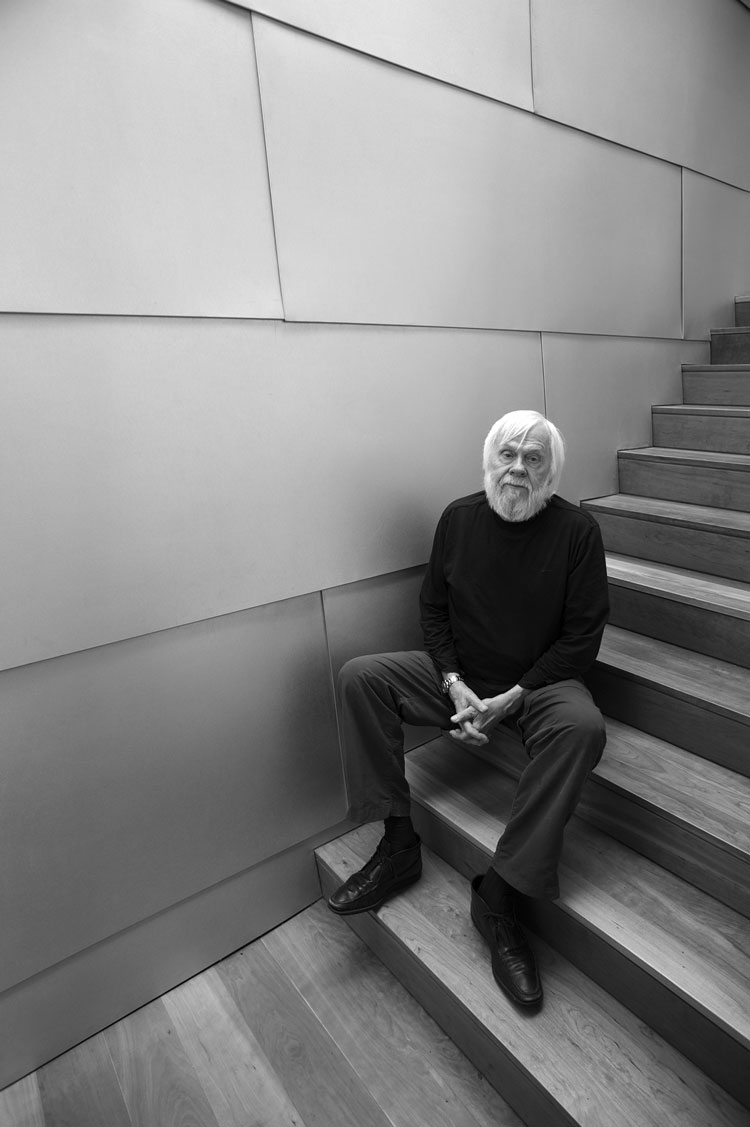

MIKE KELLEY: STRAIGHT OUTTA DETROIT

EXTRA! EXTRA! READ ALL ABOUT IT! ART STAR STOPS MAKING ART!

That was going to be my headline after hearing the remark Mike Kelley made at the close of our interview.I was wrapping up our conversation, all ready to ask the final question, like Barbara Walters: “What’s next, Mike?” But before I could, Kelley preempted me: “I’ve been working nonstop for years and years, and now I’m not in the mood to make art. I’m trying to slow down.”

Considering he was just back from his London show with Gagosian Gallery, and that that very week his Destroy All Monsters noise/art band group show at Prism gallery in Los Angeles was being installed, maybe he was just plain worn out, and perhaps being a little melodramatic. He continued, “I have a lot of things I have to do, like a big survey show that’s coming up in 2012; it’s traveling. And some other shows that have been scheduled for a long time. I just did two shows this year, and big-scale shows. So I just want to stop for a couple of years.”

It got quiet toward the end of our interview, and if I didn’t know better, I might even say he seemed a bit melancholy that late morning. It’s true, Los Angeles-based artist Kelley has been making art for a long, long time. So to say he’s taking a break is something akin to Duchamp’s famous hiatus from making art to play professional chess.

But stop making art? I hate to break the news to him, but it’s doubtful: He’s in the Whitney Biennial (for the eighth time) this year with an ongoing project. (More on this later.) That doesn’t sound much like taking a break.

Known for his stuffed-animal sculptures and his wry text drawings, his performance art, his videos, his musical activities and his writing, Kelley is arguably one of the most influential living artists, and I’ve been wanting to feature him in Artillery for some time now.

Mike Kelley, Kandor 14, 2011, photo by Fredrik Nilsen, courtesy of Mike Kelley and Gagosian Gallery. Kelley finally agreed to an interview, but only reluctantly. Last issue, our gossip columnist got carried away, and Kelley was not happy with what he took to be gratuitous character assassination. But he honored his word and met with me anyway, and I couldn’t help but be impressed by his integrity.

Kelley invited me to meet him at his office, which is actually his former studio/home, located in Highland Park on the eastside of Los Angeles. It still has the feel of a home—it actually is a house—as you enter at the back through an alley. I opened the wooden screen door to a bright spotless kitchen with shiny green tiles. Assistants were buzzing from one room to another.

Kelley greeted me as he was hastily finishing a piece of toast, which may have served as his breakfast. Casually dressed, with short-cropped graying hair, his intense blue eyes seldom caught mine. He was gracious though, and asked me if I wanted a cup of tea as he led me to the front living room, where the curtains remained drawn. There were two modern L-shaped couches and a coffee table in the middle with one lone ashtray that looked like it hadn’t seen a cigarette in a long time. There was a large Lari Pittman on one wall, on another leaned a tall pink John McCracken, and the adjacent wall had an army-green James Hayward frosting painting hanging near the front door. He told me Hayward was an old friend to whom he would be forever indebted to for recommending him for his first teaching job in Minneapolis. This ultimately led to his professorial career of over 30 years in Southern California, where he has developed a following among students who, in turn, have perpetuated his influence in the contemporary art world.

DETROIT

Mike Kelley was raised Catholic and attended Catholic School— any Kelley aficionado knows this, as Catholicism is frequently addressed in his work. So I decided to start from the beginning. When I asked him if he ever believed in Heaven and Hell, he responded deliberately, in his deep, gravelly Detroit accent, “No. I never believed in anything.” He seemed sad when he said that, with a faraway look in his eyes. Even as a child, he said he never bought into the Catholic Church: “No. I never believed in it at all. I was stuck in it. It was pounded into me, but I wasn’t indoctrinated. I suffered because I felt that something was wrong with me. I thought I should believe, and I just couldn’t understand why I didn’t.”

Aha! There’s the Catholic guilt!

But even in the first grade, Kelley told me, he remembers thinking that religion “was a load of shit.” I envisioned a tiny kid saying “This is a load of shit!”

He grew up in a working class suburb of Detroit. His father was the head of maintenance in the local public school system, his mother a cook at the Ford Motor Company cafeteria. Kelley first knew he wanted to be an artist at age 13. He went directly from high school to the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, then to CalArts. This trajectory suggested to me that he might have come from a supportive family that embraced his becoming an artist. He laughed for a long time, as if in slow motion, even a little maniacally. Then he stopped abruptly and corrected me. “No, my family did not support me in my interest in the arts. My parents were both really against it. My father basically disowned me.”

Kelley described his getaway plan back then. “Because otherwise I was going to go crazy. I was going to die. I actually had a nervous breakdown. I had no option, I had to leave my town. I would have been working in a local auto parts store for the rest of my life.” He paused, with those faraway eyes again, and added as an important afterthought: “I chose art, not to become successful, because you couldn’t make a living from being an artist at that time. It was a profession I chose specifically in order to be a failure.” This is a poignant statement, considering the nature of the art world today. Artists in the past truly were rebels and iconoclasts, not career-driven puppets.

In his early days, before Cal- Arts, Kelley delved into what was around him, incorporating his life into his art. “I was interested in hippie anarchist culture—in Detroit and Ann Arbor, that meant the White Panther Party. They put on concerts and poetry readings; they wrote manifestos about how bad capitalism was. I read John Sinclair’s writings, and I said to myself, these people are like me! I’m not crazy!” He explored the avant-garde and was deeply influenced by Dada. “The psychedelic underground was just an extension of the historical avant-garde. And I decided that I should be an artist—either that or a writer. I was particularly inspired by the writings of William Burroughs.

“When I was in high school, a group of students formed a recycling center. There was no organized recycling at that time. Working at that center, I discovered that there was a world of magazines about culture. I ripped articles out of these, and I basically taught myself about contemporary art. When I went to college, I was much more knowledgeable about it than the other students.” Smashing cans and breaking glass… and reading Dada! Mike Kelley learned about contemporary art in a dumpster, basically.

In junior high, Kelley switched from parochial to public school and acquired two art teachers. “One of my high school art teachers was a real macho guy. His paintings looked like Francis Bacon’s. The second art teacher was a closeted gay man; he had to be closeted, I don’t think an openly gay man would have been allowed to teach in the public school system at that time. He taught the craft classes,” which Kelley says he wasn’t into. But he took Kelley to exhibits and “This man was my replacement father. I won a statewide student arts award and had to go to a dinner ceremony in another city. This man went with me instead of my parents. I recall that everyone laughed when I introduced him as my teacher, because you were supposed to have brought your parents.”

It seemed to all come together right there, all the strands of his rambling and transgressive career gathered in the story of his Midwestern upbringing: the Catholic-school trauma, his teenage White Panther experience, and the tutelage of his latent- homosexual high school crafts teacher who took him to art exhibits. Roll this all into one ball, and you have the artist Mike Kelley!

CALARTS

Mike Kelley might not be a household name, like his contemporaries Cindy Sherman, Julian Schnabel and Jeff Koons. It would also be difficult to lump him in with that crowd aesthetically. For one thing, Kelley was doing performance art in the ’70s, which was way more subversive than the fine arts scene at that time. He performed with underground rock musicians. His work was unconventional, unmarketable and uncategorical. Kelley stayed in LA, when his above-mentioned peers went to New York to pursue conventional art careers.

Kelley had and continues to have a name around town—from mentor to comrade—and being from Los Angeles is definitely a factor in Kelley’s sensibility—along with Detroit, always Detroit.

A lot of Kelley’s work draws from personal history, and one as rich as his would seem to provide endless material. He shrugged his shoulders when I remarked upon this but was willing to see where I was going. I asked him if he was from a dysfunctional family.

“All nuclear families are dysfunctional,” he replied. “That’s my belief.” Then he paused. “My family wasn’t dysfunctional in the sense I was beaten or abused, but my mother was a complete control freak. She wanted to control everybody’s life, and it caused a lot of psychic damage. I’d say that my mother was a phallic mother, and my father was just in the background.”

Kelley was the baby of four children in a family of six and describes himself as “the troublemaker. In my family, art was considered to be what communists and homosexuals did.”

So your family didn’t understand you at all? “No, no. I was a Martian.” Kelley repeats this with a combination of nonchalance and conviction. “A Martian, a commie and a fag.”

I pointed out that that sounded pretty damn dysfunctional, maybe even abusive. He neither agreed nor disagreed.

So Kelley got the hell outta Dodge as soon as he could. He went straight to Ann Arbor “because that’s where all the freaks were. When I decided to go to graduate school, the only two schools I applied to were CalArts and the Art Institute of Chicago.”

Kelley decided on CalArts mainly because Alan Kaprow was on the faculty. “But when I got there, he was gone,” he said. “CalArts was really focused on New York. Students went to New York City as soon as they graduated; instead, I was driving into Los Angeles and checking it out and discovering a really interesting art scene. I met artists my age, especially coming out of Otis, people like Bruce Yonemoto and Jeffrey Vallance. I met Chris Burden, Alexis Smith and artists of that generation as well.”

The Los Angeles art scene was much younger then, and more intimate. “There were very, very few galleries and no contemporary art museum. But there were alternative spaces, and as soon as I graduated, I became involved with LACE. I was on the committees for many years programming shows and events.”

STUFFED ANIMALS

My first real encounter with Kelley’s work was at Rosamund Felsen gallery on La Brea back in the late ’80s. The piece was a tattered worn blanket with grimy stuffed animals placed in the corners. Above it were black-and-white snapshots of people smearing chocolate (one hoped), on the same blanket, using the stuffed animal as props.

I had never seen anything like it before and it made a huge impression on me. I assumed Kelley was thumbing his nose at the art world, but he rejected that theory. He told me it was the first series of work that made money for him. “I realized it was simply the subject matter. It wasn’t my intention that I hooked into this weird thing about hearth and home. People are so invested in their childhood.”

Kelley was a little perplexed by this back then, because that’s really not what the work was about. “I didn’t make that work for that reason. It surprised me. And that’s what led me to go on to do this work about life-repressed memory syndrome.”

A lot of Kelley’s work invokes psychotherapy, so I had to ask if he’s been in therapy. “I’ve been in therapy, off and on, most of my life. I also studied psychology in school and I read deeply on the subject. I’ve always been very interested in it.”

When I asked if he thought therapy was a scam, he answered without a beat, “Yes. But it’s a scam you need at the time.”

GAGOSIAN

Kelley’s work today sells for as much as a million dollars in auctions. I congratulated him on this apparent mark of success. “I don’t follow auctions, ” Kelley responded. “The galleries do that, I don’t want to know how much my work goes for.”

Granted, Kelley never sees any of that money if it changes hands in secondary market auctions, but the mere fact of the sale should boost the price of one’s current artwork, shouldn’t it? He responded dutifully, “It could, or could not. It might up the value of that particular period of my work. I have works that sell for tremendous amounts of money, and others that I can’t sell at all. I’m not necessarily going to capitalize on an inflated auction sale, that’s what I’m telling you.”

It seemed strange to me that, for such an abrasively uncommercial artist, success had found him. “Now that you’re with Larry Gagosian, you must feel like you’ve made it to the top,” I said.

“That’s a long story,” Kelley replied. “Mark Francis, who works at the Gagosian gallery in London, is a fan of my work. He invited me to mount a show there. This was when I was working on ‘Day Is Done’ [a feature film installation]. I had decided to leave Metro Pictures in New York, after showing there for over 20 years. I was locked into the gallery pecking order, and I realized I was never going to do better in New York if I didn’t switch galleries. At some point I said to Mark, ‘Day Is Done’ is a big show, on the scale of a museum show, it’s a waste to present it in London. I want to show it in the New York gallery. Surprisingly, they agreed to this. It was a real gamble. But luckily it worked out. The show was very successful and radically changed my reception in New York.”

Kelley showed with top LA galleries early on. He started with Mizuno Gallery, Rosamund Felsen, then Patrick Painter. Then Gagosian.

Larry Gagosian is known for his empire of 11 international galleries and a strict business approach to art, therefore it wasn’t surprising to hear Kelley say, “Gagosian Gallery, unlike other galleries I have shown with, is not very familial. I knew most of the artists at Metro Pictures personally. Gagosian is run in a much more businesslike way. Artists come and go.”

Mike Kelley in his outside studio in Highland Park, December 2011, photo by Tyler Hubby ONE MONTH LATER

When we went to shoot photos of Kelley, he seemed much more upbeat. He even brought along the striped shirt I suggested, similar to the one he wore in a youthful photograph included in Dirty, the Sonic Youth album he designed. That’s when he sprang his Detroit project on me, something he’s been working on for several years.

I reminded him that he said he was going to stop making art.He just mumbled something, then stared into the camera.

It didn’t seem the right time to talk about the project, so I arranged a phone interview. Two weeks later, I asked him, “What’s this Detroit project Mike?”

“I’ve been working on it for years. I wanted to work with a real structure, so I wanted to try to buy my childhood home,” he told me over the phone.

This is something you forgot to tell me? I scream to myself.

The Detroit project, it turns out, may be Kelley’s magnum opus. To explain it as best I can, Kelley returned to the Detroit suburb of his childhood and tried to buy the house where he grew up, in order to create a site-specific work. But the homeowner wasn’t interested, and after exploring other options, Kelley settled for replicating his home (after a fashion).

The structure will be built on the grounds of the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit. It will be a replica of his home but with a forbidden extension; a basement, two stories deep, each level mimicking the floor plan above, evoking dungeon labyrinths.

All these elements are still on the drawing board. What Kelley has completed so far is a façade of his house—a sort of detachable face, about the size of a mobile home, that can be placed on and off a truck. (The façade is not simply a flat wall, but a three dimensional unit that fits onto the main structure.) The piece is called Mobile Homestead, and two expeditions have already taken place, starting from MOCAD and ending at the Kelley home in Westland, which resulted in two documentary films which will debut at the Whitney Biennial this year.

This had all started as a project that Kelley wanted to do for personal reasons, not for public exhibition. But when Artangel, a London-based arts-funding organization, offered to sponsor the project, along with MOCAD, Kelley made some revisions and compromises and basically found himself doing public art, foregoing the original game plan.

The Detroit project is almost too fraught with psychology and dysfunction. The basements, the tunnels, the mazes—way too Freudian, even for me. But there it is.

Kelley continues to talk about this project as a public piece that was never meant to be public. Kelley left Detroit, but did he really leave it behind? He says the stuffed animals had nothing to do with childhood. (Really?) He says he needs to stop making art for a while, but now he’s working on a huge project that could be one of his most important pieces to date.

I think Kelley’s intended hiatus was just wishful thinking. His work is about personal history, his childhood, his hometown, psychology and dysfunction—things that could easily feel like an emotional burden. But as Kelley told me, being a conceptual artist is about ideas—and how does one shut those down?

The Stedelijk Museum is organizing “MIKE KELLEY: Themes and Variations from 35 Years,” scheduled to open at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam in December 2012. After Amsterdam the show is expected to travel to: Centre Pompidou, Paris; MOCA, LA; and MoMA PS1, New York.

See Mike Kelley’s work in the Whitney Biennial 2012 opening March 1, 2012. www.whitney.org

Find Artillery: Killer Text on Art at your local bookstores or newsstands nationwide. You’ll find Artillery at Barnes & Noble bookstores too. Or Subscribe online.

-

SOAP DISH

The mid-afternoon New York City traffic is uncharacteristically brisk on my way to interview performance artist Kalup Linzy. I arrive in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, half an hour early, with my photographer. Linzy greets us at his unmarked live-in work-space basement studio wearing a shiny dark gray satin shirt, white boxer shorts with orange and brown hibiscus flowers and a pair of rubber flip-flops.

Welcoming us in, he exclaims, “I know I told you 2 p.m., because The Bold and the Beautiful goes off at 2 o’clock.” Linzy pauses, “I mean, I can make exceptions.”I am grateful, because this man is serious about his soaps. His most acclaimed work is a series of self-made soap opera videos, some of which are All My Churen, Da Young and da Mess and the ongoing serial “Conversations Wit de Churen.” They are equal parts gender-bending satire, daytime high drama and genuine heartfelt homage.

Kalup Linzy, “Keys to Our Heart,” 2008, still from digital video Before excusing himself, Linzy announces that he’s going to make some popcorn because he has the munchies. He returns with a bag of microwave popcorn, wearing a brunette shoulder-length fuchsia-tipped wig. We want to take photos outside to catch some of the early spring light, but Linzy objects, “I can’t be going out like this; school will be getting out soon. I don’t want that kind of attention. You know how some high school boys can be.” He pauses, then adds, “But of course I’ll beat their ass!” The threat is difficult to believe. There is an easy grace about him: his newly added tresses framing his deep soulful eyes, his wide soft smile caressing the scruff of his beard.

Kalup Linzy, “Keys to Our Heart,” 2008, still from digital video The wigs, high fashion and glamour that have become a hallmark of Linzy’s work don’t necessarily define his real world. “I’m not transgender; it’s not a lifestyle for me. I just use the aesthetic of drag in my work, but I don’t think I’m a drag artist either. I just decided consciously that whenever I was going to appear that I would be dressed up and performing because I think of myself as a guy who is pretty boring,” he says laughing. “I mean, that’s what the work is, but I didn’t necessarily want to be my characters from the videos. People are annoyed that it isn’t real, but I’m like ‘whatever — get ready!’ As people misunderstand, they’ll research my work more. There are many layers to a man putting on a dress. We’re all drag queens and drag kings, anybody who’s performing to create an identity.”

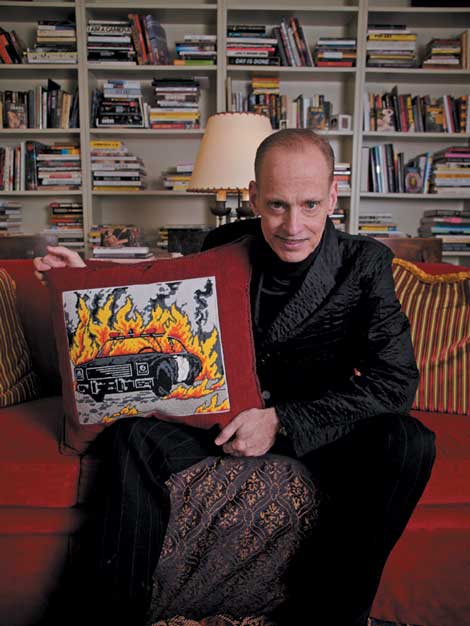

Linzy’s identity seems delightfully complex. He counts his influences as everything from daytime dramas, old black-and-white Hollywood movies, the romanticism of the Harlem Renaissance to Def Comedy Jam and the sitcoms of his childhood. He draws artistic inspiration from Andy Warhol, John Waters, Glenn Ligon and Lyle Ashton Harris. Munching on a handful of popcorn, Linzy muses, “When I was in college I had this Black Male Body book. I remember that exact moment I saw Lyle Ashton Harris, in like a tutu. I connected that to John Waters in my mind, and that sort of began to give me the freedom to do my work.”

Despite Linzy’s rather grand ascension into the art-world elite, he seems fairly unaffected by it. “I feel like the world is my art community anywhere I go. You hang out with the people that you’re around and working with and let the energy come and go. It’s like a fleeting experience. But I really do feel like the world is my home.” One of the “elite” that Linzy has been hanging out with recently is actor James Franco. They met in 2009 when Linzy was performing at a party for Art Basel Miami Beach. Last year, Franco asked Linzy to join him on General Hospital during his stint playing a deranged artist/serial killer, Robert “Franco” Frank. In an art-imitates-life twist, Linzy played Franco’s musical collaborator singer and performance artist, Kalup Ishmael.

This was a “full-circle moment” for Linzy: “I grew up wanting to be on a soap opera. I grew up wanting to be a filmmaker, a director and wanting to sing. I incorporate all this stuff into my art. So when somebody comes along like James Franco and says, ‘You wanna be on General Hospital?’, of course I’m going to say yes. The whole point of me doing the videos is because I didn’t think a soap opera could ever happen to someone like me. I didn’t believe it at first, but then I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, this is really happening!’” Linzy is grinning. “It was a big event in my life! I had to rethink, because it really wasn’t supposed to happen in a million years. Especially because I had decided to be openly gay and not give a shit and instead just express it through my work. But it gave me the confidence to do more and follow more of my dreams.”

Linzy is reflective when talking about those early years growing up in Clermont, Florida. “When I started making art in my late 20s, I was confronted with things that I had missed or was missing, things I needed to confront and deal with. Like I grew up — my mother didn’t raise me. She was schizophrenic and on drugs for a period of time. I realized I had abandonment issues, but I would not deal with them. Moving to New York made me look that in the face. Just to really look at it and know how it affected things I did. It made me want to be a giver, to feel good about something. There are certain things that I didn’t get, and so I became more inclined when I was making my work to make something just for myself, or people who are like me to identify with and enjoy.”

Upon first impression, Linzy’s work may seem like zany high-camp performance art. It’s challenging to watch his soap opera video series and not get sucked in by the characters. You immediately want to tune in to the next episode and see how it all plays out — a common soap opera strategy. “In comedy, the tragedy happens first, and then the journey back from that is normally humorous, you know, to try to heal it,” Linzy says.

Kalup Linzy, Photo by Cecilia De Bucourt High and low art brazenly crash into each other in Linzy’s work; any notion or division between the two is unimportant to him. While grateful for his success, he is unimpressed by art-world politics. “I remember being at MoMA, and I basically told the audience that I didn’t care what they thought, and I think people probably didn’t appreciate it too much, but I felt like I had to set myself free from these other people’s opinions. All they talked about was these crack addicts in the ’80s, but my mother was one. They talk about being gay, but I am one of them. They talk about being black, but that was me. Everything I felt I was a part of was being marginalized. I had to set myself free from all these opinions to be able to live.” Linzy pauses, becomes quiet and crumples up the popcorn bag. “It’s not the easiest thing. I think it’s important to care, but you have to have some kind of detachment at particular points in order to just survive and not emotionally kill yourself. The work became about my own healing and hopefully other people get something from that. I’ve done a good job with it. I’ve grown, and I’ve learned. It’s okay to let go of things you didn’t get and not dwell on it … and it’s okay to be liked. Everything doesn’t have to be so heavy all the time, you know. Early on I was just doing things so I could be accepted, but now my work is really about accepting myself.”

Linzy gets up and loads a dance mix on his laptop; the music floods the room. Suddenly we’re all up on our feet dancing and laughing. His words echo in my mind: “Everything doesn’t have to be so heavy all the time.” The photo shoot begins. Linzy serves up a powerful supermodel turn to the camera with an “I’ll beat your ass” diva glint in his eye, and suddenly I can plainly see a man in a wig who can take care of business if and when he needs to.

Greg Walloch is a writer and performer in Los Angeles. For more information, visit www.GregWalloch.com.

-

MILF AS MUSE

It is difficult to imagine John Currin’s work adorning walls more modest than those of the uptown Gagosian Gallery in Manhattan. Currin’s subjects have become progressively more well-heeled as his career has advanced. His signature subjects of yore—the ludicrously big-titted women and the frail women in bed and the nymphettes clinging adoringly to wilting bearded aesthetes—are a thing of the distant past; he has now entered a sphere of affluence commensurate with the incomes of the select few who can afford to collect his paintings, which now sell in the million-dollar range. And why shortchange him? He is one of the most interesting painters around, justifiably extolled for his technique. There are other comparably gifted modern masters (Vincent Desiderio, Lisa Yuskavage), but none who ply their exquisitely wrought brushstrokes in the service of perversity quite as cleverly as Currin.

Though they do not comprise the bulk of his oeuvre, it is Currin’s depictions of the sex lives of the rich and complacent—in which porno-derived tropes of the Sapphic variety are transposed to upscale surroundings—that receive the most attention. The most prominent piece at the recent Gagosian show, The Women of Franklin Street, was a celebration of afternoon delight in which three upper-crust MILFs pictured in the throes of self-congratulatory sensuality, pleasure one another in a sumptuously appointed living room. Foliage rustles against a paneled window and an immaculately wrought tea set occupies the foreground. Another work in a similar vein, The Conservatory, features an erotically abandoned nocturnal music practice with plenty of middle-aged spread spilling out of black lace lingerie, and clitoral stimulation tastefully concealed by skillfully rendered folds of drapery. These paintings verge upon the grotesque; they are neither aesthetically inviting to the viewer nor sympathetic to the subject, but they are provocative and they hold one’s eye.

Women of a certain age have long been Currin’s special province. Women, as he put it in a well-circulated quote that got him into a lot of the right kind of trouble, “caught between the object of desire and the object of loathing.” Women like the graying dowager in The Old Fur, who opens a fur coat to reveal a “well-preserved” body, while taking a wistful sidelong glance. Many of Currin’s women sport these wistful expressions, as if casting a backward melancholy eye at the pleasures of their youth.

It is easy to imagine Currin smiling to himself as he works, tickled by the nervous laughter his subtly incorrect depictions of the cultured classes are likely to induce in the beholder. His stance of sardonic ambiguity makes people a little uneasy, but he never lays it on so thick—the paint or the premise—that one can tell exactly where he’s coming from. He never quite crosses the line into caricature, though he comes close with a painting called Hotpants, which resembles a Norman Rockwell composition. It’s the one work in the show that features men, if you can call them that. A gauzily-painted ponce in tight shorts primps in front of a full-length mirror, while a similarly attired tailor fusses over him. The absurd vanity—and vulnerability—of those whose wealth has inoculated them against reality is often captured by Currin, as in the treacly Dogwood Thieves, wherein two blithe blondes bedizened in sun hats, ribbons and flowers luxuriate in stolen moments, blissfully impervious to worldly concerns.

A different kind of awriness pervades each painting. They are all a little “off’’ in one way or another, enough to make one wonder what’s “going on.” In Flora, a diaphanously-negligéed blonde reclines over a basket of fruit while disappearing into the corner of the painting at an angle that throws the viewer off, while Big Hands appears to be a straightforward portrait of an attractive blonde, until one notices her thick masculine arms and hands. And what’s with the portrait of Constance Towers?

There are an abundance of blondes and strawberry blondes on display, but the brunettes steal the show. Here, with two paintings, Mademoiselle and The Reader, Currin further muddies the issue by playing it straight. With these simple renderings of women lost in seductive abstraction, he arrives at an arresting combination of classical portraiture and pinup art.

These works hark back to the days when portraiture was the domain of the aristocracy. Currin updates the tradition, eroticized and filled with art historical references. Whatever his position, nobody else does what he does, and the results are capable of reawakening one’s sense of wonder at what an artist is able to do by simply applying paint to canvas. Some dissenting voices might argue that such expertise in technique is wasted on frivolous subject matter, but there is no denying the power and originality of the work.

-

A Ketchuppy Good Time

I was urged electronically to go see Dutch theater company Wunderbaum on its last night in LA at the REDCAT with no details other than superlatives (which, however, managed to get a bunch of us on that contact list out). I knew it had something to do with LA artist Paul McCarthy’s work, and the troupe was pegged as “raw” and “political.” They had been developing the work as artists in residence for several weeks at the CalArts venue.

The first two-thirds of the performance set up a reading of emails sent among cast members leading up to the evening’s performance, starting back home in Rotterdam. It seemed to be a legitimate avant-garde theater trope; an excruciating and honest look at the development of a theater piece becoming the drama. There were considerations of audience, collaboration, cultural translation, personal agendas and the illusive Big Idea. Included was the reluctant participation by a naive layperson — an attractive young bookstore owner representing the average, educated Dutch citizen — outraged by the publicly funded, arguably obscene McCarthy statue in a public square in Rotterdam. The offending work, unaffectionately nicknamed Santa Butt Plug, depicts a giant gnome holding a bell in one hand and a large sexual aid reminiscent of a Christmas tree in the other. The earnestness was amusing, and we felt let in on the joke with the “real actors,” and among people who like confrontational art. Angry citizen would come to LA to confront the artist right back.

Paul all the time, photo Wunderbaum. The email exchanges were so sniping and authentic that I dare say most of the audience was somehow merry to believe that these were actual transcripts. They wove the verisimilar with actual events, such as an L.A. Weekly theater critic Stephen Leigh Morris interview (the preview article for the play based on the interview assumed the topic of challenging Paul McCarthy was legitimate) and approaches to the artist himself. The troupe meanwhile was encountering an arts funding crisis in Los Angeles and the U.S. far more severe and intractable than the one they were in danger of losing perks from back home in a country that would support this type of somber self-indulgence. So when in the final act the whole cast (including, of course, the ingénue) exploded in an homage/parody of a Paul McCarthy-themed food and bodily fluids orgy, suddenly the whole absurd carnival was revealed hilariously. Obviously, now, the first part, with unwitting audience and media participation in the farce was a brilliantly choreographed and written play.

In the lobby afterwards, when one of the troupe’s actors was having a drink next to me at the bar, I hesitated to ask about details of the set-up, wanting to remain in the not-quite-sure what the real story was. My response was similar to the exhilaration of another favorite spectacle this year, the Banksy film Exit Through the Gift Shop. The experience of being caught up in the play of levels of narration was somehow both classical and cutting edge. These two had the cathartic effect of challenging perceptions, having my seat unsteadied by the machinations of clever manipulators, while considering notions of the arts’ role in society, and having a bloody (ketchuppy) good time.

-

Burning Man of Love

Though the annual festival known as Burning Man has received the occasional serious sniff from the art world, my overall anecdotal accounting of the festival rep in what one might call the high-end international art world has been one of mild disgust and pity. In general, art worlders like nothing better than to sneer at the post-hippie amateurs, as urbane Parisian aristocrats might sneer at their feudal country cousins right before both lost their heads. It’s easy to dismiss Burning Man (as opposed to documenta with its lower-case, self-serious Mittel-European pretensions or the Venice Biennale — which more often than not is a cavalcade of vaguely nationalistic bureaucratic cock-ups) as there’s no hierarchy of taste enforced, the works of art trotted out prefer experience over critical reflection and are largely uncommodifiable (exempting of course the costs of your ticket, transit, and survival, also payable in Kassel). Artistic participation in Burning Man looks bad on CVs and will hardly convince a trophy-hunting billionaire (or his Bard-educated advisor) to invest. The whole thing could, however, be considered by some lights to be a “kind of carnivalesque folk ritual” or at least some version thereof.

Michael Smith went to Burning Man as Baby Ikki, one of the artist’s long-running performance persona (constituting an 18-month-old as played by Smith, now almost 60, wearing a knit bonnet and white Crocs). Collaborator Mike Kelley stayed away. After the fact, Kelley and Smith edited the many hours of footage down to a movie that plays on six screens within the installation of their exhibition, called (mockingly? earnestly? both?) “A Voyage of Growth and Discovery.” This iteration took place at Kelley’s monumental studio in the Farley Building in Eagle Rock, following an inaugural showing last year at the Sculpture Center in New York.

Production stills photographed by

Malcolm Stuart. Courtesy of West of Rome

Public Art, image courtesy of West of Rome

Public Art, photography by Fredrik NilsenThough much of Kelley’s work draws from the psycho-spirituality of thrift store finds, the work in the installation looked all too easily cadged from the real Burning Man: a metal geodesic half-dome with stuffed animals (once a Kelley standby) sewn to its carpet, a jungle gym, a metal rocket with some plastic flags, a semi-abandoned VW van with a throne in the back made of more plush toys (though this time much dirtier) and a mock Burning Man made of metal junk depicting a reaching Baby Ikki. Though the visual language seems wholly appropriated from the Mad Max dystopia/Utopia of Black Rock City, they also oddly reminded me of proper works (buyable from your local Gagosian outlet) by the significant international artist known as Mike Kelley, creating in my mind some kind of Venn diagram of high and low, a strategy oft employed by Kelley thoughout his career.