The early 20th-century’s turn towards modernism in painting was a decisive shift in interest away from artistic representation of acts of witnessing. Abstract art—which now seems to dominate many visual demesnes including the decorative and graphic design, and sets the agenda for contemporary painting practice—is about a different kind of personal account, one not dependent on history or observed phenomenon, but on the artist’s facility to invent, to interpret, to play, and to condition our expectations.

Still, narrative painting persists. Several well-known contemporary artists use narrative devices in their work: Chris Ofili, Angela Dufresne, John Currin, Lari Pittman and William Kentridge all come to mind. This essay will examine the continuing significance of narrative through the work of three painters with distinctly compelling idioms: Jane Corrigan, Nicole Eisenman and Raqib Shaw.

Jane Corrigan’s work in her first solo show at Kerry Schuss (September through October 2014) represents perhaps the most pared down version of painting narrative: the portrait with precipitating action occurring offscreen. In the paintings Hurt Girl (red) and Hurt (red yellow blue) (2014), an adolescent female clutches her knee with a look of worry, panic and incomprehension on her face. The brushwork is done in sweeping, loose strokes; everything looks blown by the wind, in tumult. Underneath the girl’s hand pulling her knee to her chest, a red stain leaks out. We are not shown how the injury occurred, though we are given clues: she’s an athlete, a soccer player who now realizes that her body, an instrument of speed and fine, dextrous control is also vulnerable. Corrigan conveys the experience of adolescent girls using their bodies exultantly and encountering the important milestone when their bodies hurt and/or bleed.

The viewer will assume the painter is acting as witness, and this assumption gives the painting its emotional force. The narrative could be fiction, but its figurative style, and the quotidian nature of the incident suggests this happens to girls everywhere, perhaps to the narrator in the past. The witness now acts as chronicler, whose pivotal gesture, being made outside the picture frame, is her own hand indexically “pointing” to herself as witness via her painterly point of view. Witnessing is a crucial part of this narrative, because being an eyewitness empowers the narrator to inform us.

Deft storytelling works this way, knotting together details from a single incident to compose a larger account. In making this painting, Corrigan collapses exposition, argumentation, description and character development into a single frame. We are given all the information at once in a simultaneous dispatch of layered meanings. This condensed nature of her content is matched by the economy of her technique. Corrigan employs an alla prima method, painting into previous layers that are still wet, working quickly and expertly to build up an image. Using this method, Corrigan gestures towards Renaissance and Baroque heroic portraiture as rendered by Velázquez, Hals, and van Eyck, but makes her subjects contemporarily relevant.

- Nicole Eisenman, Sunday Night Dinner, 2009, Courtesy the artist and Koenig & Clinton, New York, Collection of Arlene Shechet, New York

Alternatively, Nicole Eisenman puts back in the frame what Corrigan leaves out. In her satirical and painterly allegories, she peers quizzically at our absurdity. In Commerce Feeds Creativity (2004), Creativity is a naked woman painfully trussed up with a rope that crushes her breasts while a malevolent character stares her down, force-feeding her some sort of gruel which she has dribbled on herself, futilely trying to resist taking in more. It is a metaphor for the desperate, tyrannized life of many artists, but one not delivered seriously. Commerce and Creativity are farcical characters, comically drawn. We are supposed to laugh at the tragedy.

Similarly, in Sloppy Bar Room Kiss (2011), the interaction between the protagonists is so abject—two heads with eyes closed, lying horizontal on a table surface have wormed towards each other to attach as if feeding—that the viewer will likely laugh, being released from the traditional decorum that often rules visual depictions of the desire for sex or intimacy. Much has been said about the humor in Eisenman’s work, and this aspect is obvious in these paintings.

- Nicole Eisenman, Sloppy Bar Room Kiss, 2011, Courtesy of Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, photo by Robert Wedemeyer

However, Eisenman’s protean painterly stylization is what makes her astounding as a storyteller. She uses distinct painting techniques to indicate differences in her characters, and differences between them. In Sunday Night Dinner (2009), for example, each character is rendered independently: some in impasto, others in a layered, pictorial style, still others in a thin, washy transparency. Eisenman varies the skin tone shading, the brushwork, the angle of depiction, the lighting, and the internal coherence of each face, giving two people pig snouts, one cartoonish, two-tone highlights, and the character closest to the foreground a wavy,

expressionistic form. She dips into her expansive toolbox of painting styles to inform us of the distinct energies between people. In Sunday Night Dinner, indifference or scorn, keen interest and bliss are all on display. One person is intrigued by the naked woman, while another disdains her, and someone else gives affection to a character who seems likely to never return it.

- Nicole Eisenman, Commerce Feeds Creativity, 2004, Courtesy the artist and Koenig & Clinton, New York, Private Collection, New York

Eisenman brings to the forefront the idea that having more than one body within the picture frame, you have drama, just as more than one body in a room evokes politics. In fact, in her work you have both. In each painting where she has a body meet another body, we feel an expectant frisson, because in that meeting we have politics, psychology, sex or domination—all the fraught issues that must be negotiated because we are not alone. Narrative in visual art can do this subtly and well: make us alive to the possibilities of human interaction. Looking at her work one is sensitized to the semiotics of facial expression, the energy of gesture, the possibilities of meeting.

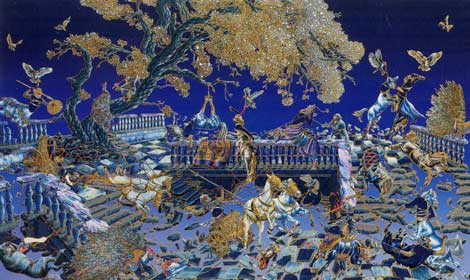

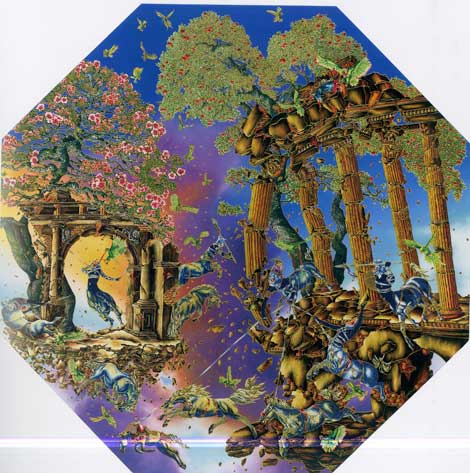

Raqib Shaw, in contrast, brings us to narrative on a much grander scale. His stories are rapturous. They are versions of the legends we tell each other about our creation, our evolution, our wars and conquests, revolutions and ruptures. Shaw renders these epics in a scale and intricate, colorful stylization commensurate with their magnificence. However, for Shaw magnificence is a function of historical and cultural distance—his references are to Persian and Indian antiquity, Japanese Shinobi sketches, Northern Renaissance painting—the further away they are in time and geographic space the more they are shrouded in myth, and therefore the more their resurrection in lush, glittery, dramatic painting seems like a revelation.

In his “Paradise Lost” series, his paintings depicting war between hybrid beast creatures are astonishing in their almost delirious detail—and in their dramatic exposition. There are seascapes festooned with rhinestones, glitter and enamel, featuring underwater conflicts between marine chimera. There are monkeys with wings, anthropoid bodies with the heads of tigers, centaurs with the hindquarters of zebras, peacocks and lizards with fantastically long tongues. These characters ride chariots, throw spears, fly wondrous gold nets, shoot arrows from bows and attempt to garrote each other with long golden chains. All this menagerie is painted in saturated hues that span the chroma spectrum: blossoming reds, flourishing greens and coruscating golds never allow the eye to rest. All the while, the martial action occurs against a backdrop of crumbling, pillared edifices falling into the obscurity of lost history. In Shaw’s work everything is in flux, and it’s all caught in the moment of toppling into the sea. The drama of falling action immediately preceding denouement keeps us transfixed.

The paintings’ central conceit is creating worlds like that of the Mahabharata, which revolves around conquest, struggles for dominance. There are several possible emotional responses to this, and rather than horror or sadness, Shaw chooses marvel. He fills his worlds with supernatural creatures and demigods more fantastically endowed than we are, their mystical status emphasized by the stupendously painted surfaces of starkly reflective enamel inlaid with vibrantly colored stones glinting like jewels. This work is overwrought in its reverence, verging on camp. The emotional response these paintings seek to engender in the viewer is awe, undergirded by the painter’s gesture of pointing beyond himself, into the sky, where beings above or beyond us battle out their inscrutable agendas.

Humanity’s great fictive epics and origination narratives have produced wonder and dread in us. But these attitudes do not train our critical faculties to make sense of our own struggles. Shaw operates in a fictive imagination that trades our bodies for metaphors and ideals we will never have, but continue to desire. Still, his narratives, like those of Eisenman and Corrigan, begin to be meaningful when they inform us of our tendencies, our habits, our confidential matters that have collective importance. Narrative is an old form, but in the hands of these painters has contemporary resonance. In Eisenman’s paintings, sensitivity to the politics of difference is celebrated through the nuance of technique, rather than ignored, or made into polemical slogans. She brings playful articulation and political awareness together organically. And as the youngest artist among them, Corrigan updates the tradition of figurative painting, imbuing urgency to an awareness of female bodies in active form—running, doing, becoming—and compelling the act of painterly witness to again become crucial to the medium.