In a series of evocatively posed large photographic diptychs entitled Thoamada II, Vuth Lyno expands common frameworks of sexuality, family and memory.

This work is an outgrowth of an earlier series of photographic and audio portraits of individual MSM (men who have sex with men) entitled Thoamada (2011). That work was comprised of a suspended circle of nine large-scale color photographic portraits and audio material. Here Vuth questions the line between private and public, inner and outer—the same faces appear inside and outside the circle, but your relationship to them differs. The portraits and stories derive from an intensive workshop with a professional facilitator and nine men who have sex with men (MSM) and exchanged personal stories over two days with the aim to build intimate public dialogue about, and among, LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender) communities.

In both collaborative series, subjects represent their lives as thoamada—normal, everyday, commonplace. These Khmer LGBT communities have diverse voices. Vuth asks us—individually and collectively— to reconsider the bounds of love. In an interview excerpt, Vuth shares his approach.

Artillery: What was your process working with your subjects?

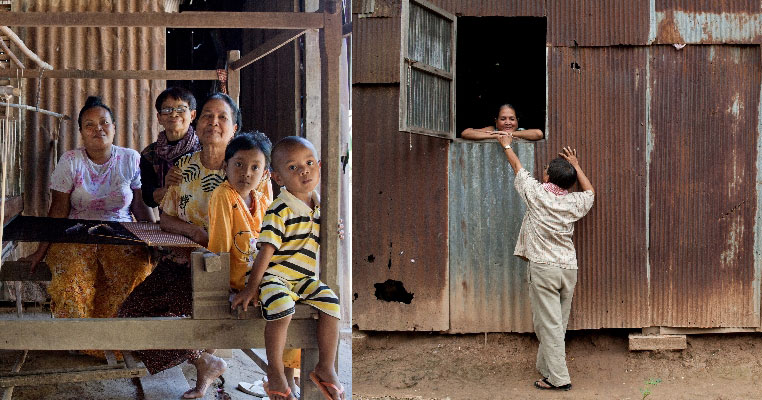

Vuth Lyno: I interviewed people together with their families, inviting them to share their stories and journey. After the conversation, I asked them to pose for two different photographs. One was a simple family portrait inside their house. They decided on their dress and pose.

For the second photograph, I asked them to collectively choose a memory to re-enact, improvised with their belongings and surroundings. I proposed that they select one of their most memorable moments in life as an individual or as a family. We re-created that scene together. Some chose a story they shared in the earlier interview, some chose another memory. Together we worked out clothing, and prepared a backdrop around the house to match the scene they remembered. Then they performed that moment and I took the photo.

How did you find your subjects?

Some of the participants I met before during Cambodia Pride over the last few years. Some were introduced to me through Cambodian LGBT networks. A few are my friends or were introduced to me through friends.

Who are the intended audiences for these images?

I wish to connect mainly to Cambodians. I want them to see these family portraits as common, like any other: they are all thoamada.

The image on the left is a narrative recollection, something that may or may not relate to the subject’s sexuality, but I find it very significant—it reflects a part of how they define themselves and a part of the journey in shaping their family.

How does Thoamada II shift “traditional ideas of what makes a family”?

My experiences with all the participants were extremely rewarding and I have learned so much. Each family determines their own definition of family, notions of gender roles and family structure, and ideas of what leads to a good family. There were families with two mothers, there were lesbian families with one as a father and another as a mother, there was a family with a gay son who also had a transgender sibling, there was a family with an ex-soldier mother and a lesbian daughter. All these challenge stereotypes a great deal.

Are there any significant interactions, stories, or memories you’d like to share?

Each family shared a fascinating story. At times, some participants got very emotional, and me too. For example, in one family, Pisey remembered that when she was little she was always waiting for her soldier mother to come home, while the mother was in the battlefield. Today, she tells her mother that it’s now her turn to conquer—not on a battlefield with the enemy—but in advocating for rights for Cambodian LGBT people.

How has Khmer LGBT visibility and acceptance changed? What are current obstacles?

I noticed that Khmer LGBT visibility has increased dramatically over the past five years. The work by volunteer-based groups such as the Rainbow of Community Kampuchea (RoCK), which organizes Cambodia’s annual Pride, has been playing a critical role. Many Khmer lesbians, transgenders and gays throughout the country now have opportunities to meet, build networks, organize and voice their concerns in public forums.

Nevertheless, there are many different levels of obstacles ranging from family rejection, community discrimination to social neglect. Other roadblocks include negative attitudes toward

LGBTs and poor legal protection. Despite the generally tolerant culture, and that young people tend to be more open and accepting than older people, Cambodia is still a conservative society. People seek acceptance and fear society’s rejection. But society starts with families. Change must start from acceptance at the family level.

You are an artist and organizer with strong ties to Cambodia as well as many other international communities through your creative activities. How do you identify as an activist, and as an artist?

I see myself more as an artist, except my art practice so far tends to engage community in talking about social issues and promoting collective voices. I like challenging the boundaries of art—its form, who can make it, and what it can do in a real world full of social injustice. I also enjoy the collaborative process because I can learn so much from people I work with. I love human stories.

What does family and community mean to you?

Family is whom I come home to. Community is whom I work with. Both together make me feel a strong sense of belonging and purpose.

What constitutes family? What are the ties that bind us, then and now? Yes, this love is thoamada.