There she is, as if alive. She is haunting and haunted; a Hollywood Miss Havisham in her crumbling mansion. She was once a real person, a somebody, a fond recollection. But now gone gray in her decaying cinema—with seating just for one—she resurrects herself nightly in black and white. She is still big, she tells herself, it’s the movies that have become small. In her day, Norman Desmond hit bullseyes in the fat part of the target, she played to the mainstream and she was the main attraction. Yet, while Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard portrayed a faded star of the Hollywood firmament there existed a parallel cinema industry directed at a much smaller audience, also in black and white but with the accent on the black.

The history of Black Cinema, or “race films” as they were called, has been rightfully excavated by film historians but these movies, made between 1910 and 1950 with all Black casts, though not always Black directors (Edward Ulmer, of Detour fame, directed Moon over Harlem), remain primarily social history instead of cultural artifacts. In Fade to Black, his affecting and illuminating installation, Gary Simmons has extended his current Black cinema resurrection practice and elevated it to a yet richer and discerning expression. It is a fragmented and shuddering film still and title sequence, and it is as haunting as any motion picture classic, at once enduring and ephemeral.

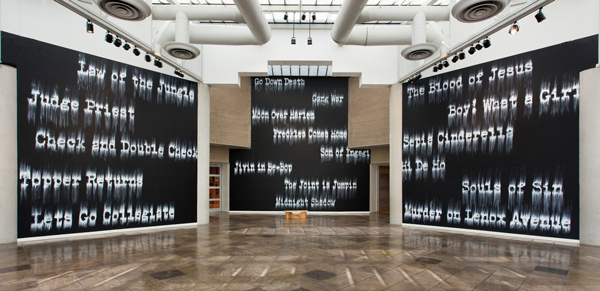

Gary Simmons: Fade to Black at the California African American Museum. Photo: Brian Forrest

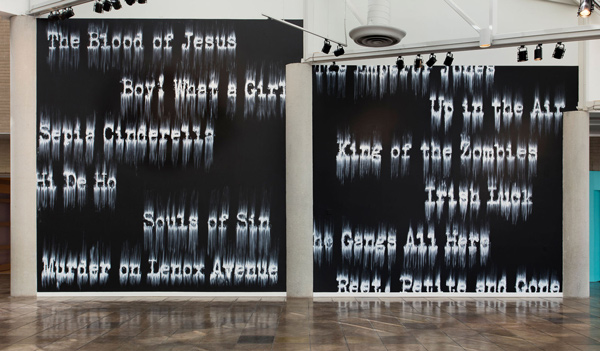

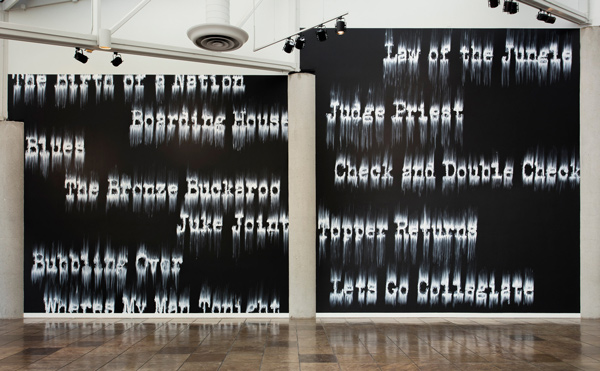

Its installation is of epic scale, a makeshift cinemascope of five vast blackboards, suggesting lessons to be learned. Positioned in the cavernous foyer of the museum the panels recede deeply toward the center much like cinema architecture itself. Each of these oversized slates contains numerous titles of “race films” but the text is shifted from side to side as if the film projector’s gate and shutter are out of sync. Some of these films featured legendary performers who later and occasionally featured in mainstream Hollywood productions—Cab Calloway, Lena Horn—but for the most part these films and performers have been shunted to a segregated back lot of movie history. The panels, two stories tall, are near matte black and contain luminous white text in courier font, a favorite typeface for screenplays. They have been hand-smeared by the artist and appear liquid, as if in the process of being washed away. Represented here are films nearly lost in a history that constituted a definitely separate, certainly unequal, but absolutely essential entertainment for African Americans who could finally recognize themselves—segregated as they usually were from the actors on screen and the privileged patrons allowed to enter the cinema on the ground floor—as the hero, the villain, and the romantic interest: Bronze Buckaroo, a horse opera with a singing cowboy; Murder on Lennox Avenue, a respected man is falsely accused; Sepia Cinderella, unrequited love is requited.

Gary Simmons: Fade to Black at the California African American Museum. Photo: Brian Forrest

The recent successes of Moonlight, Get Out, and Black Panther, with substantial Black casts and Black directors, show that lessons have indeed been learned. Yet, while African-American moviegoers were outnumbered on Black Panther’s opening weekend, 63 to 37%, they attended at a rate three times that of their representative population. Instructive certainly, but also evidence that a racial empathy gap remains in White audiences’ appreciation of Black films. It may be an acquired taste, but it is essential learning.

Gary Simmons: Fade to Black at the California African American Museum. Photo: Brian Forrest

Or, as Boss Jim Gettys warned Charles Foster Kane, “You’re going to need more than one lesson. And you’re going to get more than one lesson.”

Gary Simmons, “Fade to Black,” July 12 – December 31, 2018, at the California African American Museum, 600 State Drive, Exposition Park, Los Angeles, CA 90037, caamuseum.org

0 Comments