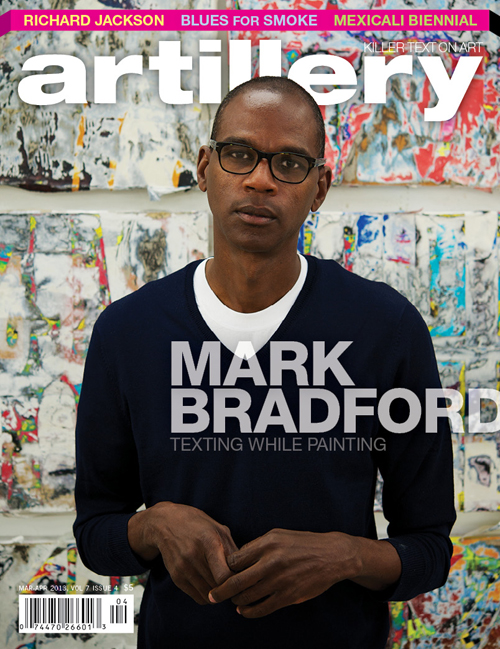

From the shaded parking lot, a stark beam of light shines through the loosely shut double doors of a nondescript white brick building. It is late morning, and the sun is already beginning to assert its presence as I approach the now-defunct Regen Projects gallery. It...