Liberty Cabbage. Freedom Fries. Whenever a reactionary quorum congregates one can be certain no good can come of it. While our senate stages a work stoppage on judicial appointments, and a viable presidential candidate—best known for his government shutdown...

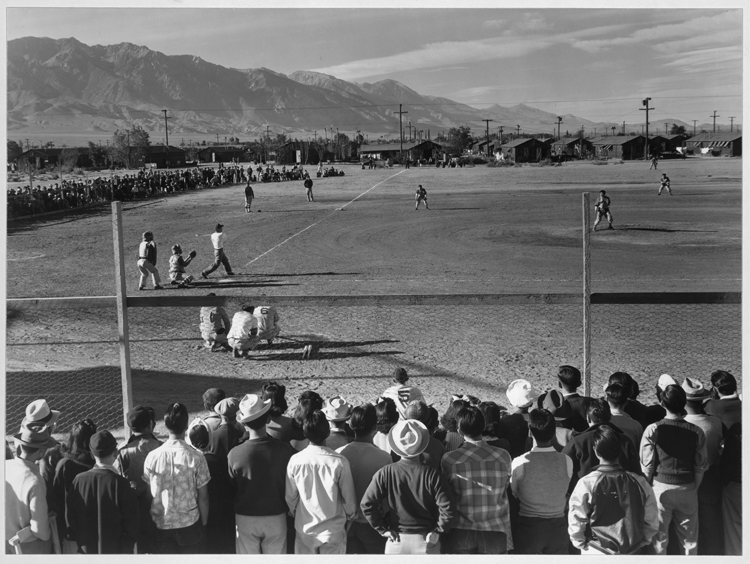

TWO VIEWS: PHOTOGRAPHS BY ANSEL ADAMS AND LEONARD FRANK

read more