Your cart is currently empty!

Byline: Marieke Treilhard

-

Empathy Through Technology: Re-examining Vulnerability

The provocation of vulnerability has long been a mainstay of impactful art. Video and film media, given their reliance on the staging of exposure and emotional confrontation, are no exception. An exhibition at Young Projects in Los Angeles curated by NextArt explores these very themes, looking at the ways in which technology can interpolate human vulnerability and probe the complex interstitial spaces of mediated human encounters. “Vulnerability: The Space Between” features both contemporary and historical works that paradoxically re-sensitize affect through facsimile, performance, surveillance, virtual reality, film, and installation. In an era of increasing detachment and impoverished cultural empathy, the exhibition reminds us of the fragility and pain of the human condition and the healing and redemptive potential of its acknowledgment.

Kate Hollenbach, phonelovesyoutoo (31 days of cellphone recordings) (2016). Courtesy the artist. The exhibition opens with a series of recent and historical performance-based works from the 1970s on, including works by Marina Abramovic, Bas Jan Ader, Chris Burden, Sophie Calle, Valie Export, Regina José Galindo, and Yoko Ono, among others. One of the earliest incarnations of video was as documentation of the more ephemeral medium of performance.Both monologic and interactive examples set the stage for this exploration of corporeal and emotional vulnerability. In Blind Spot (Punto Ciego), a performance piece by Galindo from 2010, the artist stands naked on a pedestal in a gallery and allows blind tourists, unprepared for the nature of their encounter, to touch and explore her body unhindered by resistance or self-protection. This physical act of touch, innocent in its unknowingness and yet explicitly dangerous in its lack of prophylactic barrier speaks volumes to the simultaneous freedom and bondage of contact.

Similarly, the legendary and often imitated performance by Yoko Ono, Cut Piece (1964), shows the artist sitting on a stage in ”her best suit” with a pair of scissors ominously set in front of her. The audience is told they may approach and cut a small piece of the fabric clothing her, taking it with them. The imminence of potential danger is apparent, but the supremely vulnerable act of submitting to the will of the other and trusting in their adherence to an unspoken social contract of mutual care is palpable.

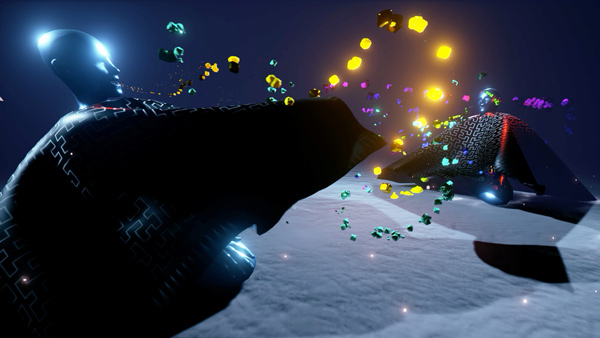

VVVR by Plus Four (2017), a Virtual Reality Experience for two people. Courtesy of the artist and Young Projects. Other works in the exhibition, such as Coming Out Simulator (2014) by Nicky Case, attempt to create a facsimile of self-disclosure and confession. As a kind of interactive game, the viewer is given the chance to navigate a moment in the artist’s personal history, simulating the conversation in which he comes out to his mother as gay. This personal revelation captures a feeling of communicative despair in which self-exposure becomes painful and negating because of the hurtful reaction elicited by the other.

VVVR by Plus Four (2017), a Virtual Reality Experience for two people. Screen grab. Courtesy of the artist and Young Projects. Another piece in the show, VVVR (2017) by Plus Four (Ray McClure and Casey McGonagle), offers a positive counterpoint to communicative risk, as an interactive virtual reality in which two must participate and ”connect” virtually by donning Oculus headsets and finding common ground in an immaterial context. Their voices and emissions activate the exchange within a virtual void, becoming ecstatic visualizations of speech and sound within a vaguely utopian, though tenantless, space.

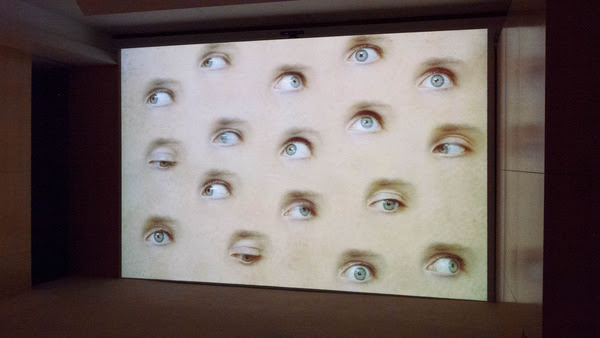

Luxloop, If The Walls Had Eyes (2014), an interactive projection, installation view. Courtesy the artists. Other works in the exhibition flirt with themes of surveillance and omniscience such as If The Walls Had Eyes (2014) by Luxloop (Ivaylo Getov & Mandy Mandelstein), a digital installation of blinking human eyes that watch and follow the movements of the viewer as they move within the range of their ”gaze,” and Lauren (2016) by Lauren McCarthy an ”Alexa” like device capable of human empathy who surveils the home of participants while intuiting their needs with an anticipatory thoughtfulness.

Lauren McCarthy, Lauren (2017), web-grab. Performance, interactive website and installation. Courtesy the artist. Among the works in the exhibition, I Love You And That Makes Me God (2017) by Fawn Rogers resonates deeply, tapping into something darker and far more unsettling in the vein of a confessional. This immersive installation requires that the viewer enter a secluded, darkened space at the back of the gallery. Cornered by two screens in which nearly 60 individuals are video-taped repeating a phrase that simultaneously feels like admission, threat, and mantra, we are left feeling vulnerable ourselves, accosted at times, and seduced at others. As each subject repeats ”I love you and that makes me god” with varying degrees of honesty, artifice, disingenuousness, sympathy, and even aggression, the full spectrum of human vulnerability seems to unfold before our eyes, both in the delivery and in our receipt of its offering.

Mandy Mandelstein, Touch (2013), an interactive installation for two people. Courtesy the artist. True vulnerability is an admission. Whether it be the need for love, the search for meaning, the acknowledged imperfection of self, the persistent feeling of worthlessness, or the fear of loss, it is all in one way or another dependent on the existence, recognition, approval, or disavowal of the other. Rogers captures the problematic coexistence of these impulses in her piece, not to mention the flawed social contract of reciprocity that is to hold everything in place—but often fails to protect or return. ”I love you and that makes me god”—the phrase itself is repellant in its threat of subjugation, but inexplicably coercive in its implied promise of affection.

Much in the same way that Abramovic’s viewers would burst into tears when confronted with empty stillness, so too are Rogers’ viewers overwhelmed by the rhetorical offering of love and its fractious condition of power. Standing alone with this loaded installation, undeniably staged to feel confrontational and imperative, something pathological is happening in our moment of repeated exposure. Each subject’s delivery, as captured by Rogers, is different, and thus each individual’s experience of the mantra is singular, making the potential for mixed meaning and ambivalent reception endless. Love and our need for it become something potentially redemptive, harmful, extravagant, and conditional, as variegated as the word itself is reductive.

“Vulnerability: The Space in Between” offers a disarming experience of admission and disclosure. Alone in the darkened gallery space, surrounded by technologically mediated experiences, we are brought strangely closer to an empathic encounter than were we out in the realm of the real.

“Vulnerability: The Space in Between,” October 5 – December 29, 2017 at Young Projects Gallery, 8687 Melrose Ave. #B230, West Hollywood CA 90069. www.youngprojectsgallery.com

-

Marc Horowitz

Humor is often a neglected muse in the production of fine art. Seldom is it thought of as a legitimate field of cultural inquiry or a productive platform for the creation of an aesthetic. Los Angeles-based mixed media artist Marc Horowitz, known for his socially experimental practice and his penchant for pranks, however, begs to differ. His current exhibition, “Interior, Day (A Door Opens),” attests to the symbiotic possibilities of comedy and art. In his first major solo exhibition of painting, sculpture and drawing, Horowitz offers a cleverly staged mash-up of art historical references and popular culture, with the affable lightness, comedic timing and understated depth for which he’s known.

With an art practice driven by social experiments, made in the spirit of waggish relational aesthetics, Horowitz has relied heavily on social media and web-based platforms. “The National Dinner Tour” (2004) was spurred by a cheeky intervention made while working on the commercial production of a Crate & Barrel catalog. The artist wrote his name and number on a dry-erase board featured in a home-office product shoot, and upon distribution of the catalog, the intervention undetected, Horowitz received more than 30,000 calls. He spent the subsequent year on a nationwide tour making dinner plans with strangers. In another notable project funded by Creative Time entitled “The Advice of Strangers” (2011), Horowitz crowd-sourced everyday decision making for an entire year of his personal life; everything from what he should wear to what he should eat, he offered up to public scrutiny and popular opinion. By co-opting commercial marketing strategies, Horowitz has cleverly reasserted a disobediently human quotient into an otherwise impersonal and quantified approach to social information.

Marc Horrowitz, (Shouting): Hey! Where are you all? You’ve got visitors!, 2015, courtesy of Mark Horowitz studio and Depart Foundation. Unique in his resistance to cynicism and his desire to connect, his work conveys playful irreverence; it is a candid offering activated by self-conscious social poetics. Horowitz also enjoys drawing attention to the very act of viewing; even his titles reveal the inner-workings of this near cinematic sensibility: Ding. The Elevator Opens (all works 2015) and The Camera Moves Close Until Her Ear Fills The Frame, are cases in point. And Horowitz wants his viewers to become a part of the staging. A master of the mise-en-scène, Horowitz arranges objects, people, references, encounters, but preserves enough room for accident and aberration, allowing the end-result to emerge in the spirit of contingency. Unexpected outcomes and spontaneous results, though marshaled by clever positioning and gestures, allows viewers to lose their balance long enough to see something new.

“Interior Day (A Door Opens),” represents a return to painting for the artist after 15 years of working in more ephemeral and experimental media. The exhibition is polished and thoughtful, but just like Horowitz, doesn’t take itself too seriously. The paintings are gestural, funny and complex; the sculptures combine classic statuary with junky bobbles worthy of an Olympic-level hoarder—and protruding phallic noses, somehow a constant reminder that the comedian is lurking somewhere in the wings. A cardboard cutout gondolier frames a phenomenal large-format painting in a back room, and a campy, giant oversized bunch of plaster grapes surprises you around a corner. At every turn there is something unexpected, just enough to create the productive space of imbalance in which Horowitz thrives.

Show ends Jan. 30. 2016

-

All-Female Cast

This September, LA gallerist Anat Ebgi launched an unheard of exhibition program committed to featuring only female artists for an entire year: a concerted effort to correct a persistent imbalance in the art world. According to Ebgi, “The exhibition program will serve as a template for the future of our gallery, as we take on more women artists who have a completely unique and uncanny use of material and gesture in their work. This idiosyncrasy with material and form is something that really drives me to work with, and discover, new female artists.” Ebgi goes on to point out that the percentage of women artists on commercial gallery rosters throughout the United States tends to linger at an iniquitous 30%, a bias she is challenging head-on.

Anat Ebgi, photo by Michael Underwood. In 2012, Ebgi opened her eponymous gallery on La Cienega Boulevard in Culver City, expanding her program and space to accommodate more ambitious projects. Last March her gallery was included at The Armory Show for the first time, exhibiting elegantly constructed material “paintings” by Luke Diiorio. Her roster is carefully curated, beautifully concise and features emerging and mid-career artists like Amie Dicke, Elias Hansen, Nicholas Pilato, Sigrid Sandström and Margo Wolowiec. Ebgi’s interest in process, materiality and the unavoidable inheritance of history is clear.

Jen DeNike, Jori <3, 2015; from upcoming project “If She Hollers.” At 19, in Miami where she had grown up, she moved to a then-nascent arts district (before Wynwood existed as we know it) and was immersed in the burgeoning art scene there, living with artist friends and working as a preparator at the Miami Art Museum. She then relocated to New York City and began curating independently at 21, eventually completing a Master’s degree in Curatorial Studies at Bard. Upon graduating in 2008, an economically inauspicious time to say the least, Ebgi took a chance on LA. She soon opened her first space with partner Annie Wharton in November of that year in Chinatown. “The Company,”—the gallery’s name intended as a tongue-in-cheek reference to the ongoing financial collapse—was an ambitious undertaking given the moment, but it worked and set something in motion.

Jen DeNike, Boxer, 2015; from upcoming project “If She Hollers.” By this time, the young gallerist had already begun to do what she does best: establishing long-lasting, supportive and creatively fruitful relationships with artists, and had secured a following from her independent work as a curator in New York. This symbiotic growth of gallery and artist—the success of which is the true test of a dealer—speaks volumes to Ebgi’s efficacy as an old-school gallerist with vanguard tricks. As a case in point, Jen DeNike—a complex artist working in photography, performance and video to blur the boundaries between the choreographed and the observed—has been with Ebgi since the beginning, even figuring prominently as a subject of her Master’s thesis.

A solo exhibition of new works by Jen DeNike will open in November featuring new installations and videos that explore issues of gender, race and identity through familiar pop-cultural references and appropriated cinematic roles. Other female artists scheduled for 2016 include Margo Wolowiec, Samanatha Thomas, Amie Dicke and Sigrid Sandström. “The art world is a deeply unequal place for women,” says Ebgi, “I always remind myself of this… We decided to schedule a year of all-women shows not only to balance out this dynamic, but to also override notions of the male-centric nature of artistic production. [Galleries] are spaces to foster a community of artists, relevant ideas and narratives. I strive to do that.”

Images courtesy of Anat Ebgi gallery

Jen DeNike: “If She Hollers”

November 14 – December 19, 2015

ANAT EBGI

2660 S LA CIENEGA BLVD,

LOS ANGELES, CA 90034 -

Straight From Cuba

“Straight from Cuba” at Lois Lambert Gallery, is an unexpectedly compelling exhibition. To subsist as a contemporary artist in present-day Cuba is no small feat. With little to no resources at their disposal in the way of art materials and economic support, and political censorship to impede free expression at every turn, artists in Cuba must be driven by something far more powerful than a desire for notoriety or commercial ambition. The three Cuban artists featured in this exhibition display a passion that exceeds reason and it’s difficult not to idealize the kind of creative compulsion that weathers persistent discouragement with an inspiring resilience.

Showcasing the work of Alan Manuel Gonzalez, Luis Rodriguez NOA and Darwin Estacio Martinez, “Straight from Cuba” presents three very distinct aesthetic visions united by the difficulty of a shared cultural and political legacy. All three artists are exhibiting in Los Angeles for the very first time, an opportunity that would have been unthinkable pre-2013, the year in which the exit permit system was abolished. The system, in effect for some 50 years, prohibited its citizens from traveling freely beyond Cuba. With an ambivalent view of their country’s future—despite recently improved diplomatic relations with the United States and the relaxation of isolationist embargoes—all remain skeptical of Cuba’s ability to slacken the hyper-politicization that has quarantined it culturally for so many decades.

Darwin Estacio Martinez. Rosado y Verde. 79 x 52 inches. Acrylic on canvas, courtesy of Lois Lambert Gallery. In spite of the political and economic discomfort of the country, there is a deeply sown love, pride and history that binds the inhabitants and tempers the cultural fabric of Cuba. When asked whether there was a defining element that made Cuban artists Cuban, NOA—whose beautifully chaotic work emerges from stream of consciousness replied, “There’s a Cuban ingredient in every Cuban artist, dancer, writer. It’s a clear and deep sense of belonging to our home and our land.” Gonzalez, whose work is more explicitly political, offered, “I have been trying to express a kind of invisible prison. Cuba is beautiful but constrained. We have to express ourselves through metaphor in order to jump over the censorship that binds us. I’m expressing our pains, I want the message to be understood.”

NOA. La Idea Fugativa 2. Mixed Media on Canvas. 31×39.5″, courtesy of Lois Lambert Gallery.

Alan Manuel Gonzalez. Esperando un Nuevo Amanecer. 32×29 in. Acrylic on canvas, courtesy of Lois Lambert Gallery. NOA, a self-described Surrealist, captures the daily bustle and frenetic energy of his hometown, Havana. Creating intuitive works based on the impressions he distills from daily street life, he captures the improvisational nature of the culture. Streets are filled with people and chaos, a dynamic and unrelenting city hum through his dense “drawing paintings.” His poetic observations capture the ambulant energy of city life in Havana, described by the artist as a mix of architectural styles in various states of disrepair, constant cacophony, makeshift solutions for lack of resource, laundry strung from balconies, poverty and laughter. In his words: “We improvise every day. There is poetry in improvisation. You cannot predict things in Cuba, you have to look for solutions. People have to create things from what they have.”

NOA. Havana Jungle. 59 x 59″. Mixed media on canvas, courtesy of Lois Lambert Gallery Gonzalez is a hyperrealist painter. His highly detailed works are of microcosmic worlds and landscapes contained within glass vessels. The imagery of containment is intended to communicate the political entrapment and censorship Gonzalez identifies as the defining plight of Cuban culture. His visual metaphors are direct and poignant, at times painfully so, illustrating the confinement of a Cuba that withholds and denies freedom from its citizens. According to Gonzalez: “There is no journalism in Cuba. The government retains complete control. I don’t want people to be overly optimistic about what’s really happening there. I hope my work will convey the truth of our situation.” Gonzalez’ deliberate choice of a hyperrealist style is intended to illustrate clear and accessible analogies for the viewer. In a touching segue, Gonzalez shared the material ingenuity with which he creates his work. He has used the same acrylic paint cans since 2004, diluting the pigments and extending their use for as long as possible, and re-purposes flour bags as canvas substrates. As an artist in Cuba, material scarcity engenders some ingenious solutions.

Alan Manuel Gonzalez. Everything Has Its Time – Ecclesiastes 3″. 55 x 75 in. Acrylic on canvas, courtesy of Lois Lambert Gallery Finally, Martinez is a graphic painter, also from Havana, who sets up partial narratives and incomplete frames with a cinematic quality. A lover of American painters (and the stylistic debt to Alex Katz is apparent), Martinez’ paintings are about insinuation and suggestion. Citing Oscar Wilde, the artist appeals to the idea of literally conveying mystery through the visible, by creating compelling stories through the partial disclosure of seemingly innocuous and generic details. The paintings are ultimately about the possibility of what remains undisclosed and beyond the frame. Perhaps in keeping with this theme, the figures in his works remain persistently anonymous as their faces are never shown, allowing their identities to remain unspecific. Martinez’ paintings play with the ubiquity of political censorship in Cuba, intentionally withholding contextual details and explicit narratives to encourage the freedom of suggestion and inference. In his words: “Painting is a way of being free. I try to see the things we have, but my paintings communicate the wish of a generation for a higher level of freedom.”

Darwin Estacio Martinez. Azul Profundo. 79 x 51 in. Acrylic on canvas, courtesy of Lois Lambert Gallery. Straight From Cuba: Alan Manuel Gonzalez, Darwin Estacio Martinez, and Luis Rodriguez NOA

May 16 – July 12, 2015

2525 Michigan Ave, E3

Santa Monica, CA 90404