Your cart is currently empty!

Byline: Leanna Robinson

-

Ry Rocklen Zooms In On Food

The Food Group, an ongoing project by Ry Rocklen, is a comical exploration into the relationship between mankind and food. Human subjects (friends of Rocklen’s, mostly) dress up in life-sized food costumes à la Fruit of the Loom that are either rented or fabricated by Rocklen. The costumed subjects are then scanned and replicated by a 3D printer in miniature, food-sized form. The result is a collection of work that is part kitsch, part comedy, part camp, and draws viewers in to see just what exactly is going on.

Tyler, 2017, dye-sublimated gypsum, Corian, stainless steel, magnets; photo by Daniel Spizzirri. The miniature sculptures are rooted in Surrealism as Rocklen plays with the idea of scale. We are used to seeing humans in silly food costumes. What makes the project novel is the manipulation of scale. When the subjects are inside of the costumes, the food is out of proportion and too large, while when the subject is shrunken down, the food is the correct size while the subject is not. “I’ve always had this dream of making something big and bringing it back to scale,” Rocklen says in a phone conversation. In his works, the subjects are “taken for a ride.” Last October, Rocklen debuted “Food Group” at Team gallery in New York; the series will be the focus of an upcoming major exhibition in Los Angeles in 2019.

Honor and Corrina, 2017, dye-sublimated gypsum, Corian, stainless steel, magnets; photo by Daniel Spizzirri. When asked about the psychological nature of the project, Rocklen points to a few common emotions. Because these foods are familiar, there’s an intrinsic delight and nostalgia on viewing them, because who doesn’t like pizza? On the other hand , “there’s a kind of humiliation that’s going on with the costumes,” he says, and who wouldn’t feel at least a little embarrassed walking around and being immortalized as a sculpture in a giant hamburger costume.

Ry, 2017, dye-sublimated gypsum, Corian, stainless steel, magnets; photo by Daniel Spizzirri. Rocklen succeeds in bringing in pathos with his humor, something often missing in artistic works. “I kind of have the clown card, I have a kind of wry sense of humor,” he says, which isn’t surprising one bit, as it’s indeed his first name.

-

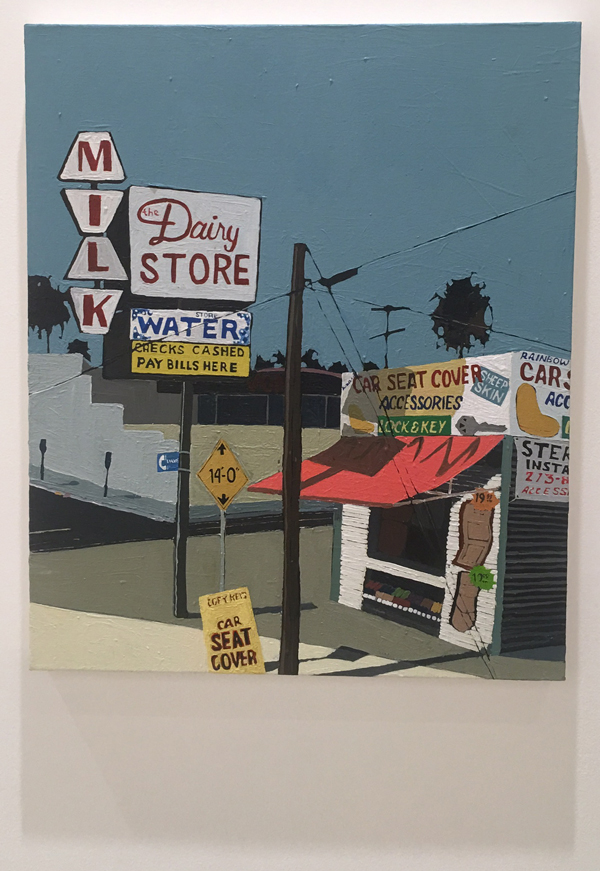

Lauren Halsey

The aesthetics and content of we still here, there (2018), Lauren Halsey’s current installation at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, are deeply rooted in Afrofuturism—a cultural philosophy that merges magical realism, science fiction and technoculture to critique the present day and historical dilemmas of black people. Typically, Afrofuturistic work features depictions of African roots, specifically Egyptian, which Halsey does through her shrines of African leaders and African rugs that line the entire installation. Other details, such as the music playing in the background and the aforementioned voiceovers are direct odes to Afrofuturistic trailblazer, Sun Ra.

MOCA featuring a work entrenched in Afrofuturism comes at a particularly timely moment, as the movement has been flung into the mainstream thanks to the music and fashion of celebrities like Beyonce, Rihanna and FKA Twigs, along with the blockbuster hit, Black Panther. Significantly, a number of other contemporary artists have begun to explore this territory as well. Historically, there is a dilemma between the reality that Afrofuturism envisions and the oppressive reality that exists.

Installation view of Lauren Halsey: we still here, there (2018) at MOCA Grand Avenue, courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, photo by Zak Kelley. Halsey succeeds at the difficult task of addressing frequently discussed issues in a way that is novel and fresh. Gentrification has been front and center in discussions about historically black neighborhoods like Inglewood and South Central. From rising housing costs, to new developments to the upcoming Metro Crenshaw/LAX line set to open in 2019, the concern to preserve neighborhoods’ cultural identities and fight back against erasure is a battle cry for many. Halsey translates this sentiment into an artistic vision that is bright, colorful, full of life and zeal, and has a deep sense of both pride and play.

Halsey’s attention to detail gives the exhibition a particularly human feeling. Notable examples include a display of oils with absurd names like “Obama” that are ubiquitous in corner stores and botanicas, a book titled “A Dib of Dis a Dab of Dat”, and signs that read “TOGETHER WE CAN” and “NUBIAN”. Hair is celebrated at multiple points in the installation, with signs advertising braiding services. In a time when banning dreadlocks is still not considered discriminatory—black men and women are forced to cut off dreadlocks and dreads despite cultural and religious reasoning, and black students are punished for having natural hair—Halsey’s detail to celebrate black women’s hairstyles (much like Solange in “Don’t Touch My Hair”) is both notable and of the moment.

Halsey has succeeded in creating a vision of her neighborhood that provides a window into how she sees it. It’s beautiful, colorful, full of detail and nuance, and celebratory of black culture. For a place that is often perceived as dangerous, dirty and needing to be “cleaned up” and gentrified, Halsey presents South Central as a paradise, and one can’t help but want to stay awhile in the world that she’s created.

-

A Bountiful Garden Party

The annual garden party fundraiser for SASSAS (Society for the Activation of Social Space through Art and Sound) had most things one would expect in a swanky fundraiser. The event took place in the private residence of Mary Blodgett and Carlton Calvin in the painfully luxurious neighborhood of San Marino. The residence, which was really more of a compound, was complete with an oddly shaped pool, private tennis courts and three or more miscellaneous buildings that seemed to house studio equipment among other curiosities.

SheKhan with Kelly Coats and Kathleen Kim

Pegasus Warning The live impressive performances took place outside; I was especially enchanted with experimental R&B artist Pegasus Warning. Artists Renée Petropoulos, Kaz Oshiro, Carolyn Castaño, Warren Neidich and Scott Benzel were in attendance, along with gallerist Charlie James. While SASSAS Director Cindy Bernard was unable to attend due to a family obligation, board members Michael Ned Holte and Devin Tsuno greeted guests in her absence.

Todd Gray The art involved in the auction wasn’t particularly rousing, but that may be because of the way it was hung. It’s often difficult to appreciate artworks in group shows, especially when they are just sitting on a table or propped up against a wall, wrapped in cellophane. Most of the pieces riffed on music and retro album covers which made for fun and amusing eye-candy. Highlights starting at incredibly low prices were by Dave Muller, Todd Gray, Amanda Ross-Ho and Kio Griffith, to name a few. Paddle 8 was the online auctioning house, where organizers had iPads so attendees could bid on the spot, although bidding remained open for 10 days after the fundraiser, which ends tomorrow (June 22)…paddle8.com/auction/sassas/

The only aspect that was a sore thumb in the whole scene was the catering. In a posh fundraiser such as this, I expected waiters with trays of hors d’oeuvres, nice wine and some kind of delicious surprises. Instead, I was greeted with King Taco as I walked up and saw the unmistakable logo on the truck outside. Look, tacos are fine, but at least hire a local business, get a taco truck that has fresh meats and tamales. The super sweet margaritas that complimented the fast food tasted just fine, albeit no wine. Tickets for this event were $100 and promised “bountiful food and drinks,” so it seems like SASSAS and I have a very different view of “bountiful.” Other than that, what a delightful Sunday afternoon garden party, and the cookies were delicious, and the auction is still up for bountiful artworks to purchase!

Photos by Felix Salazar; www.felixsalazar.com

Benefit Auction SASSAS ends June 22, 2108. Go to paddle8.com/auction/sassas/

-

Vision Valley, An Effortless Cool Factor

I was going to make fun of The Pit’s group show “Vision Valley” at the Brand Library for being a “biennial,” since everything is a biennial these days, until I actually read the press release (whoops) and realized that they were making fun of this exact thing themselves. According to organizers of this exhibition, The Pit’s directors Adam D. Miller and Devon Oder, this will be the first and only Glendale, California biennial.

Gallerygoers with peep show That’s an unfortunate fact actually, since the show of 30 or so artists was rather impressive, especially given that almost all of them work or live in or around Glendale, or the San Fernando Valley as it were. Jokes aside, the group show including stalwarts such as Lari Pittman, Roy Dowell, Kerry Tribe and uh, old-school photographer Edward Weston (apparently owning a studio in Glendale in 1910) had an element missing from many art shows—the element of play. From a brilliant video peep show by Olivia Mole, to kitsch sculptures encapsulated in glass by Mungo Thomson, much of the artists seemed to sidestep the art-world downfall of stuffiness, thus making their artworks have an effortless “cool” factor.

Kathleen Ryan, Hollow Song, 2015 The opening itself had all of the aspects of a great party, that is, except for the bar attendant serving thimble-sized servings of wine. Look, I get it. People love to drink at these things, and we all know nobody is actually buying the art. Still, I think the Brand can find it in their budget somewhere to serve more than 2-ounce pours of a wine beverage (full disclosure, this writer moonlights as a bartender).

Mike Mollett pondering glass sculptures by Mungo Thomson. As the DJ spun classic hip hits like a Tribe’s Low End Theory, we ran into the retired art-world doyenne, Rosamund Felsen, which rumor says might open a gallery. We also ran into Mike Mollett, who dished about the closure of DTLA gallery CB1 with a possible pending lawsuit. Finally the conversation drifted to Mike Kelley, as it always does (see my Top 10 things you overhear at LA Galleries list), and we passed Connie Samaras on our way out. Scribe Andrew Berardini made an appearance, and I would have stuck around longer had the wine and cheese been flowing, but like the biennial, there’s only enough for one round.

-

OP-ED: In the Age of #MeToo

The wave of women coming forward with accounts of sexual harassment and assault has swept the art world like the Santa Ana winds in a California brush fire, and all I have to say is “Finally.” Historically, women have served as objects of sexual desire within the context of art, and a blind eye has been turned to their exploitation by powerful men. Still, just because women are coming forth with their stories doesn’t mean that the art community has been particularly receptive. An anticlimactically lackluster response has led me to question: Is the art world sweeping #meetoo under the rug?

Knight Landesman When Knight Landesman, former publisher and current co-owner of Artforum, was accused of sexual harassment this past October by staffer Amanda Schmitt (among others), an open letter titled “We Are Not Surprised” was published on the internet and signed by over 1,800 people. The open letter called for the resignation of Landesman, which was fulfilled in that he was fired from his publishing position. As to his removal from co-owner, there has been no progress. And as a shareholder he continues to benefit from Artforum’s new “intersectional feminist” point of view.

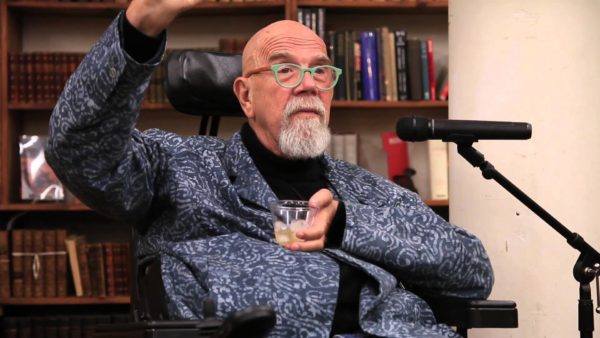

This scandal was bookended by accusations against portrait painter Chuck Close, when he was accused of sexually harassing two women. In response to the accusations, Close gave a half-hearted response, saying “I am truly sorry, I didn’t mean to. I acknowledge having a dirty mouth, but we’re all adults.” While some museums have chosen to postpone exhibitions by Close in solidarity with his accusers, others, such as MoMA and the Met, continue to show his work.

Chuck Close This question of whether or not to show Close’s work at museums begs the greater question that many people in the art world seem to be grappling with, which is how do we separate the artist from their art, and should we do so at all. In historical terms, if we were to remove all works by men who exploited, harassed and assaulted women, most of our museums would be half-empty, and there most certainly wouldn’t be any Picassos on view. (Picasso allegedly physically abused women, beat them into unconsciousness, burned them with cigarettes, and leveraged his power to sexually take advantage of models.)

On one hand, it would be interesting to imagine every museum removing all instances of sexism and works by sexual abusers in their halls. It’s a revolutionary idea—and if these institutions removed all of these works, it would provide space for minorities and women that have been denied for so long. Imagine: every piece of art by an abuser in a museum replaced by a work created by a woman artist. While this solution may be considered radical, it is no less radical than continuing to honor work by abusive men.

Giovanni da Bologna, Rape of the Sabine Women, 1583. On the other hand, many curators and artists believe that the work should remain intact despite the artist’s wrongdoings. Something I hear often, even by forward-thinking women in the art world, is the fear of creating an environment in which artists are scared of saying something that is offensive and where everyone must behave according to some prevailing cultural code. While I agree that censorship has typically acted against, not in favor of, the creation of art, the “free speech” of some, oftentimes means the silence of others. Take, for instance, established male artists who think it is appropriate to tell emerging female artists that they are “pretty little painters,” or gallery owners who tell female artists that they can “work their way in… if you know what I mean,” or male professors who tell female students “you should paint nude self-portraits because that’s the most interesting thing you could create”—all of these, by the way, have happened to myself and close friends. When men wield their power under the guise of “free speech” and “talking like adults” it often leads to an inadvertent censorship of female artist.

If museums and galleries insist on carrying artists who have historically been abusers, like Picasso and Close, there must at least be a caveat to contextualize their work. Sexually suggestive works of underage “muses,” nude paintings of women by known abusers, and works evoking a lack of sexual consent should not be exhibited without accompanying descriptions of their painter’s and society’s wrongdoings. Still, this feels like an inadequate reaction. As long as owners and curators of museums and galleries remain largely male, there should—and will—continue to be a fight for not only more female representation, but also for radical art and action for the rights of women.

-

Diane Rosenstein Gallery: : Jesse Edwards, Matthew Sweesy

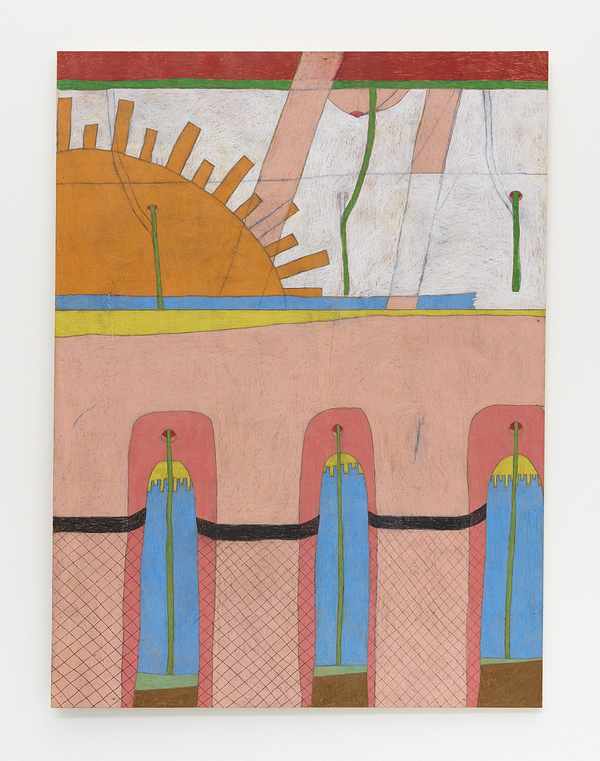

Matthew Sweesy’s “Nocturnes” and Jesse Edwards’ “Hot Town,” currently at Diane Rosenstein Gallery, are exercises in nostalgia. The two artists, while working in different mediums and styles, have a strikingly optimistic quality. Whether it’s the pop culture references in Edwards’ paintings, or the childlike explorations in Sweesy’s, the exhibitions have a je ne sais quoi that may remind viewers of simpler times.

Matthew Sweesy, Red Rose (2017). Colored pencil on panel, 48 x 36

inches, courtesy Diane Rosenstein Gallery.Sweesy’s bright, graphic drawings are the variety that would have art-naysayers complaining, “My kid could do that,” which in part seems to be his intention. The compositions are of typical refrigerator fodder—trees, a half-sun, horizons. Upon closer inspection, however, the works unfold into pseudo-psychedelic landscapes that blend eroticism with innocence.

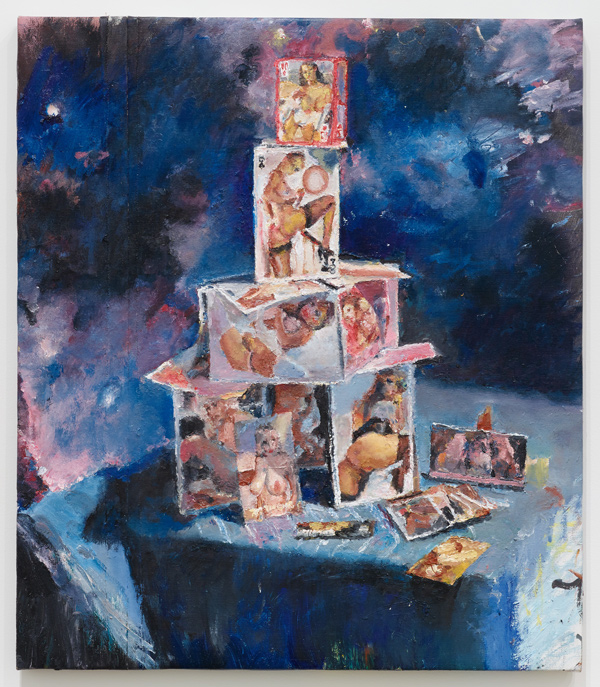

Matthew Sweesy, “Nocturnes.” Installation view, courtesy of Diane Rosenstein Gallery. Edwards’ still life paintings, which, though steeped in representational techniques, maintain a deeply subjective point of view, transforming basic items—a baseball glove, flags, melons—into statements on current affairs and the human condition. For instance, a painting depicting the flags of Mexico, the U.S., Israel, and Palestine in the same room could lead one to infer a political message, though what exactly the message entails is uncertain. The installation of Edwards’ work throughout the exhibition adds a counterpoint, and is particularly exciting with the groupings of paintings alongside sculptures of vintage television sets.

Jesse Edwards, Card House Galactica (2018). Oil on linen, 30 x 26 inches,

courtesy Diane Rosenstein Gallery.Most emblematic of Edward’s ability to blend representational techniques with contemporary subjects are Card House Galactica (2018) and Untitled (Card House #2) (2016). Each work shows a house of cards, comprised of novelty female nude playing cards—the kind you would find in a gas station bathroom for 25 cents a pack. Edwards’ stacks of tawdry cards could be seen as a metaphor for his work. With his painterly techniques and unique eye for content, he can bring any subject matter from the gutter or basic American household and turn it into something grand and impressive.

Jesse Edwards, “Hot Town,” and Matthew Sweesy, “Nocturnes,” March 17 – April 21, 2018, at Diane Rosenstein, 831 North Highland Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90038. www.dianerosenstein.com

-

The Educated Outsider: John Tottenham

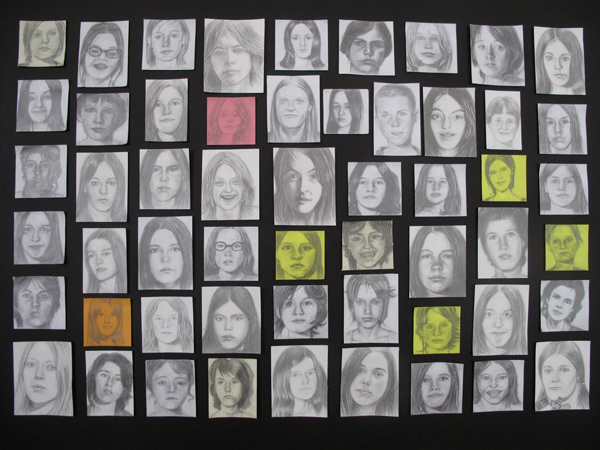

“We’ll play to 700?” John Tottenham asks, but really it’s more of a demand than a question. It’s my second week of trying to combine an interview with him on his drawings of the Manson girls (as he insists, “You don’t have to focus on that series”) and our weekly game of gin rummy. This week there are too many people in the bar and we have to wait half an hour standing around, something that both of us vocally despise.

Each meeting functions like clockwork—we complain if we don’t get our regular waitresses, he whinges over not feeling well for some toothache or heartache, we order identical drinks, and he goes to the bar to fetch a handful of paper napkins, one of which is used for scorekeeping. The rest of the napkins John uses to hastily draw portraits of women’s faces; half-distracted as he watches me shuffle cards or listens to me gripe about some insufficient lover.

John Tottenham, The Undesirables, 2014, 65 pencil drawings on paper, 32 x 43 in. (detail) John’s bar-napkin sketches remind me of his portraits of the teenage girls involved in the Manson murders. He insists that the Manson portraits are markedly different, as they took much more work, and involve more erasing than actual drawing. It’s not the technique that’s similar though, but the way he so effortlessly captures the likeness of his subjects.

Another striking feature about both the napkin sketches and the portraits are their subtle and implied sexuality. I ask John if he drew the Manson teenagers because deep down he wanted to fuck them. He answers no, but that maybe he could have. But John admits, “I projected most of my adolescent romantic longing onto them, though there was a lot to go around.”

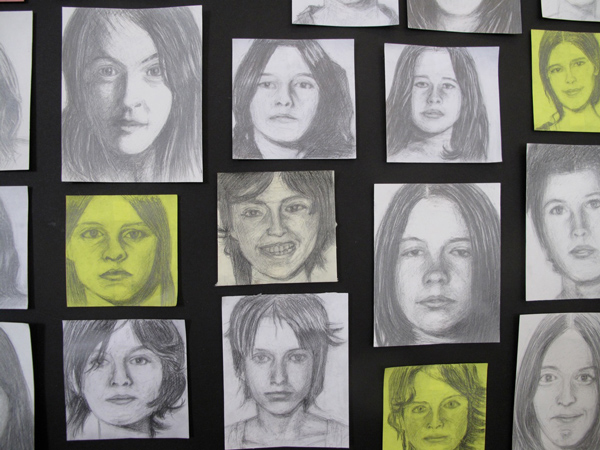

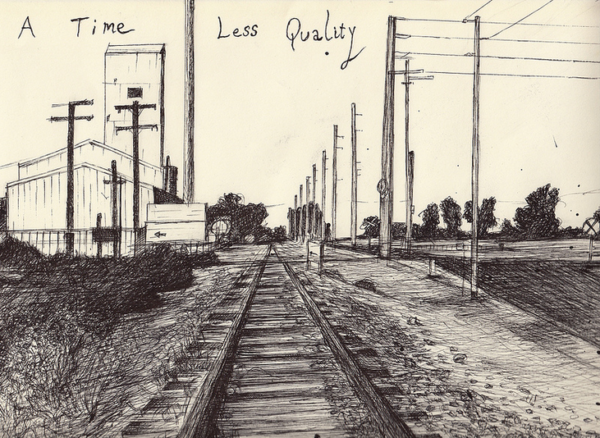

Emptyscapes John doesn’t only do portraiture, he also draws landscapes or as he calls them, “emptyscapes.” They are usually more tightly rendered and illustrated in pen or ink, and depict dilapidated small towns in the west. “I tend to find myself in those types of places,” he says. The compositions are all the same—a landscape of “timeless decay” with a line of text on the bottom. “They began as an afterthought and someone told me to write on them, so I did.” When I ask if he draws the images from memory or photographs, he answers in his quintessential self-deprecating style, “I don’t have imagination, spontaneity, or memory, and what I just said wasn’t spontaneous either.”

If I say something especially clever while playing cards, I know so because John takes out his little black notebook where he keeps his repository of quips and writes it down. That’s where he gets his lapidary one-liners that turn his haunting depictions of the emptiness of small towns into the poignant antithesis of those awful motivational posters you see in a guidance counselor’s office: “Kill off your expectations and settle in.” It only makes sense that John’s work includes text, as he is a published poet and author of such melancholic titles as The Inertia Variations and Antiepithalamia & Other Poems of Regret and Resentment.

Emptyscapes I beat him in the next hand, 80 to minus 40, and he admits that he doesn’t feel like a real artist. We are on our second drink, but it’s a screwdriver not a greyhound because the bar ran out of grapefruit juice. “I am an academic primitive, an educated outsider, I went to the worst art school in England and the only thing I learned is to drink, do drugs, and have sex.” He is disappointed when I tell him that his experience is typical.

John Tottenham is a purist. He tells me he is constantly torn between art and writing, and that he would rather spend his efforts on work that he feels to be filling a void than work that is not singular or adding anything to the conversation. He’s the same in art as in writing, as in gin rummy as in everything else. He reminds me, “Better than sex, gin rummy. You said that once. It says less about the quality of the sex life than the quality of play.”

-

Wendell Gladstone

“Fever Pitch,” Wendell Gladstone’s new collection of paintings, achieves that elusive characteristic in which the longer you look, the more you see. It may be the bright, cotton candy-colored palette that draws you in, but it’s the details that keep you looking. At the heart of “Fever Pitch” is the movement and dance of lovers. Bodies intertwine and embrace, clinging to each other in the throes of passion—though many of the women in the paintings seem to be losing themselves in euphoria more than the men. It leads me to question, are these works exploring the female orgasm?

In Solid Gold, Daddy Long Legs (2017), a nude woman bends over backwards as her breast and mouth explode like bottles of champagne—cork included to ensure the metaphor is clear. Meanwhile, in You Can Go Home Again (2017), a woman closes her eyes in bliss as a man’s hand sensually enters her mouth; she appears lost in ecstasy as her shoe slips off her foot.

Gladstone’s images of falling women being held up by unmoving, stoic men seem firmly rooted in male fantasy. The women seem to lack agency, and appear more like passive objects than active participants. Because Gladstone’s work is so rooted in the subconscious, it may be that the heteronormative, classic power structure of strong objective male, weak subjective female is less representative of the artist’s views, and is more an indication of thought patterns of our society as a whole.

Wendell Gladstone, You Can Go Home Again, (2017), courtesy of the artist and Shulamit Nazarian, Los Angeles. Then, there is the more sinister narrative afoot in the paintings. In both of the aforementioned works (along with others in the show), there are often one or multiple onlookers with menacing expressions. These (always male) voyeurs cast an uneasy shadow and impart a sense of dread that creates dynamism within the otherwise dreamy and pleasant paintings. This contributes to the fantasy aspect as well, as this added element often creates a scene where a woman lost in ecstasy is surrounded by a group of male onlookers.

These symbolic allegories breathe life and interest into the paintings, and they are facilitated by Gladwell’s meticulous touch. For instance, he uses clear medium mixed with thin tints of paint to create a stained glass effect that he layers over parts of the compositions. On the bottom section of many of the paintings, smaller bodies intertwine, move, and dance. Much like the stained glass effect, these figures are rooted in technique. Gladstone creates them by building up thick layers of paint, and then carving them out with an X-Acto knife. Using this carving technique throughout his paintings, Gladstone builds up depth that is greatly contrasted by the smooth surfaces of his airbrushed figures.

Gladstone’s work has historically suffered from trying to do too much in too little space. In this collection the artist has focused on slowing down and telling a story. He has honed his techniques and by using them consistently has achieved a calculated show that, though most likely divisive, is a display of an artist has finally caught his stride.Los Angeles

-

Zevitas Marcus: : Josh Jefferson

Is a collage comprised of assembled painted canvases a collage, a painting, or assemblage art? Does the semantics even matter? “Jabberwocky,” Josh Jefferson’s exhibition at Zevitas Marcus, plays with these boundaries. Jefferson created the collages (the gallery has labeled the works as ‘collages,’ so I’ll call them the same) by layering hand-painted pieces of cut out canvas. The canvas pieces of varying shapes and sizes sit on top of each other to create unique forms and compositions.

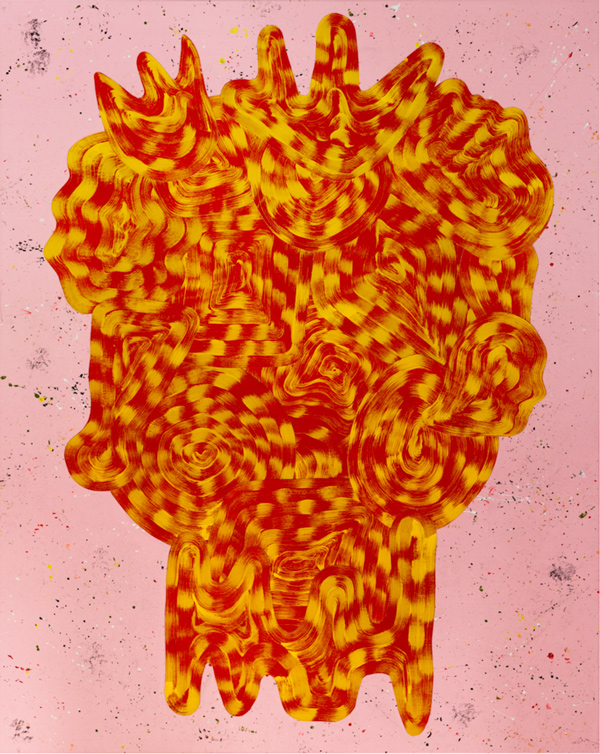

Josh Jefferson, Mrs. Nibbs (2017), courtesy of the artist and Zevitas Marcus. Jefferson’s paintings move—or at least appear to. A color theory lover’s dream, “Jabberwocky” explores abstraction through repetitive markings and topsy-turvy patterns. Each of the forms is unequivocally organic, in keeping with Jefferson’s color palette—particularly the earth-toned yellow in many of the works. And while the collages are comprised of repetitive markings, the imagery within the exhibition also has repeated imagery. Mrs. Nibbs (all works 2017) and Red Roses have strikingly similar compositions while Moon Man and The Walking Man are clearly abstract representations of figures with similar compositions as well.

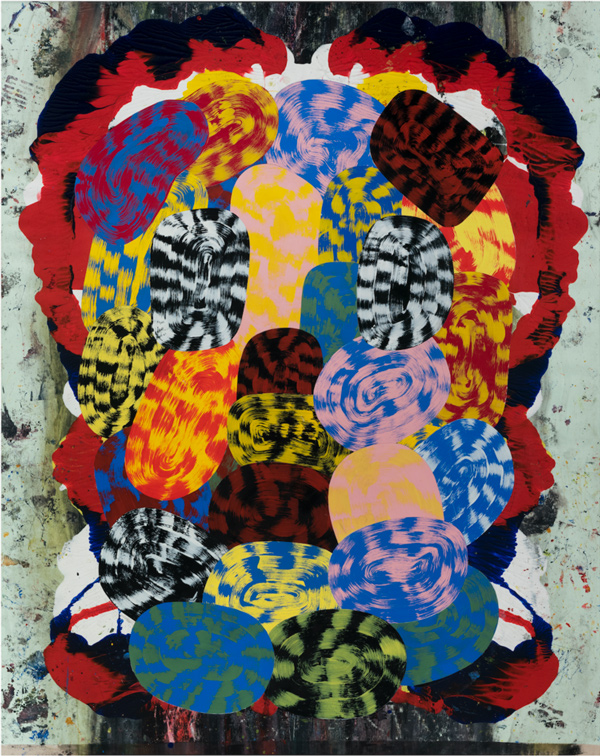

Josh Jefferson, Red Roses (2017), courtesy of the artist and Zevitas Marcus. On the note the aforementioned pieces, it becomes obvious that Jefferson has thrown viewers a bone in revealing (or suggesting) what the abstract forms are. A personal favorite is Reclining Nude With Lollipop. I’m not sure if I would have seen a nude figure or a lollipop, but because Jefferson suggested it I can’t help but put the pieces together to form that image in my head.

Josh Jefferson, Reclining Nude with Lollipop (2017), courtesy of the artist and Zevitas Marcus. With all of these moving parts, “Jabberwocky” is as playful as the title suggests. While the works seem to be created by experimentation rather than clear intention, they are nonetheless as effective in the end. One can’t help but revel in the fun.

Josh Jefferson, Jerry Bear (2017), courtesy of the artist and Zevitas Marcus. Josh Jefferson, “Jabberwocky,” January 6 – February 24, 2018, at Zevitas Marcus, 2754 S La Cienega Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90034. zevitasmarcus.com

-

Culture Coverup: L.A. Chicana/o Murals under Siege

Just as there is a certain metaphysical link between acknowledging one’s existence and looking in the mirror, there exists a similar link between the acknowledgement of a culture’s experienced reality and its representation in media.

When a cultural group lacks representation, the variety of their experiences is suppressed. At times, then, they are fueled to create an artistic response outside of the conventional hegemony. Chicano artists throughout the movement of the 1960s and beyond are known for doing just that through public artworks. What are the implications, then, when those self-created representations are erased?

¡Murales Rebeldes! L.A. Chicana/o Murals under Siege at LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes documents the life, and inevitable death (or purgatory in one case) of eight murals created by Mexican-American artists throughout LA. The exhibition is different from any I had ever been to, most notably because none of the works actually exist anymore. What is on display is a re-assemblage of parts that remained of the murals, including photographs, preliminary sketches, paintings and pieces of rubble. These scraps are relied on to give the viewer an idea of what the murals were like when they were on public view.

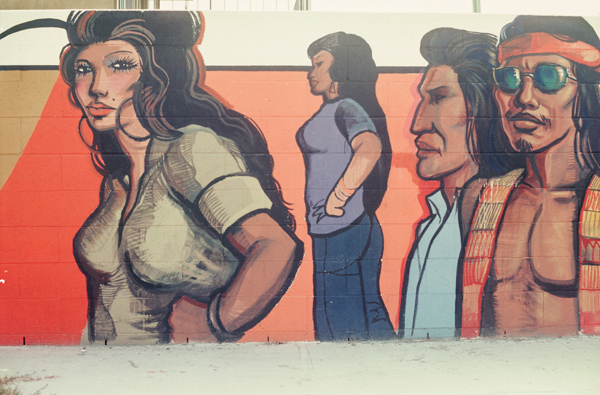

details from Sergio O’Cadiz’ Moctezuma, Fountain Valley Mural, 1974–76; destroyed 2001; Calle Zaragoza, Colonia Juarez, Fountain Valley. The archival care given to the remaining fragments greatly contrasts with the flippant actions of their destroyers. Viewers have the chance to catch a rare glimpse into the ghosts of these past murals. Many of the pieces, such as reference photos of people within the finished works, humanize and give context to the murals.

Censorship is a major thread present throughout the exhibition. Many of the murals were commissioned and approved by institutions, only to be deemed too controversial after their completion. It seemed that institutions and the public at large felt discomfort when viewing the uncomfortable reality of Chicano life and history. Sergio O’Cadiz Moctezuma’s Fountain Valley Mural (1974) was initially censored before it was inevitably destroyed. The mural, which consisted of various Chicano portraits, depicted what appears to be a young Chicano man being dragged away by police officers. The violent section was spray-painted white to block sensitive viewers from having to face what was, and is to this day, a fairly common scene.

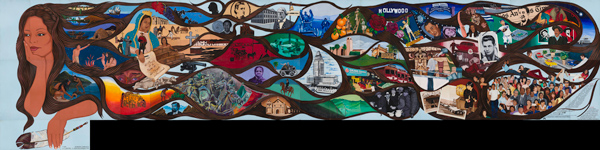

Barbara Carrasco, L.A. History: A Mexican Perspective, 1981, censored 1981, Intended site: 330 South Broadway, Los Angeles. Barbara Carrasco’s L.A. History: A Mexican Perspective (1982) was similarly deemed unfit for public view after being commissioned by Los Angeles’ Community Redevelopment Agency for the city’s bicentennial celebration. The work depicted the Zoot Suit Riots, the whitewashing of a mural by Mexican artist David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Dodger Stadium, which displaced thousands of Mexican-American landowners and families in the Chavez Ravine. The bicentennial decided to not allow Carrasco’s work due to these historical depictions. Carrasco, with the support of historians and community groups, petitioned to show the mural during the 1984 Olympic Games in LA, but the proposal was rejected.

One of the examples of whitewashing that I found most painful to stomach was that of Roberto Esteban Chavez’ The Path to Knowledge and the False University (1974) at East Los Angeles College (ELAC). The sprawling, brilliantly colored mural was painted along the side of the Rosco C. Ingalls auditorium. Above the mural was a plea to bring Chicano studies to the college. Five years later, the college president claimed the removal occurred because the auditorium needed repairs. Mysteriously, the only wall touched was Chavez’, leading to the widespread belief that the whitewashing was merely an attempt to discourage the Chicano movement at ELAC. Chavez later created The Execution (1982), a film which depicts a man being electrocuted and Chavez playing the part of the college administrator destroying a mural.

East Los Streetscapers (David Botello, Wayne Alaniz Healy, George Yepes), detail from Filling Up on Ancient Energies, 1980, destroyed 1988, acrylic on concrete, 1,200 square feet, corner of 4th and Soto Streets, Boyle Heights, Los Angeles.

Healy, Botello, and Yepes (left to right) complete Filling Up on Ancient Energies, 1980

Courtesy of East Los StreetscapersNot all of these works were destroyed for political reasons, however. East Los Streetscapers’ Filling Up on Ancient Energies (1980), which depicted such colorful, apolitical images as dinosaurs and classic cars, was destroyed by Shell Oil through what can only be described as apathy. The company later lost a lawsuit to the Streetscapers, and laws were passed to bring murals under California’s protection. While the muralists created a victory for future artists, it’s impossible to ignore how much more history the community would have if the mural was still intact.

While the censorship, destruction and abandonment of these murals happened decades ago, it plays into a larger narrative about public expression of Chicano artists and the censorship and silencing of a culture. To this day, Chicano muralists are creating new murals in areas like Boyle Heights, where the community is actively fighting against gentrification, which, it can be argued, is one of the most powerful agents of censorship.

Roberto Chavez, The Path to Knowledge and the False University, 1974–1975, whitewashed 1979, East Los Angeles College, Monterey Park While Chicano activists rally against developers to keep their roots in the neighborhood, artists continue the tradition of public art. Adrian Ulloa’s Love Our Mothers (2017) on the side of a Dollar store on Cesar E. Chavez Avenue depicts an indigenous woman with a powerful stare; perhaps she is Mother Earth, surrounded by butterflies, hummingbirds and nature. Nearby is Nani Chacon’s ¡RESISTE! (2017), in which two women touch hands in front of the earth and huge red lettering that says “RESIST.” One of the women wears a red bandana around her face—a piece of clothing emblematic of recent protests both in Boyle Heights and across the country.

While a select few murals of Chicano artists at LA Plaza are commemorated and others along a strip in Boyle Heights continue to be created, there are still many across Los Angeles that continue to vanish from lack of upkeep. In a time when public awareness of Chicano struggles—whether over displacement, police brutality or class struggle—has all but disappeared, public art continues to have a vital place in the streets and not just in the history books.

¡Murales Rebeldes! L.A. Chicana/o Murals under Siege

LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes. Runs thru March 19, 2018 -

CAAM: : Black Radical Women

Rallying against overwhelmingly white, male perspectives in art history, “We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85” at the California African American Museum (CAAM) is not to be missed. The exhibition highlights the stylistically varied work of over 30 artists and re-centers the focus to a group that has historically been marginalized and left out of both the mainstream and feminist dialogues during those decades. Groups such as the Harlem Renaissance, Spiral, and the Black Arts Movement are represented, and given the commentary provided by CAAM, the exhibition provides newly illuminating historical context and background for these diverse movements and the artists represented.

Betye Saar (American, born 1926). Liberation of Aunt Jemima:

Cocktail, 1973. Mixed-media assemblage, 12 x 18 in. (30.5 x

45.7 cm). Private collection. © Betye Saar, courtesy the artist

and Roberts & Tilton, Culver City, California. (Photo: Jonathan

Dorado, Brooklyn Museum)Many of the artworks are distinctly political, conveying the urgency of calls-to-action—the work of Betye Saar in particular has this effect. Saar’s pieces contrast racist images of people of color with iconography of the Black Power movement to create striking symbolism. The Liberation of Aunt Jemima: Cocktail (1973) features a bottle with a “mammy” figure on the front that has been turned into a Molotov cocktail. Her film, Colored Spade (1971) uses similar pairings, meshing derogatory images with depictions of black power.

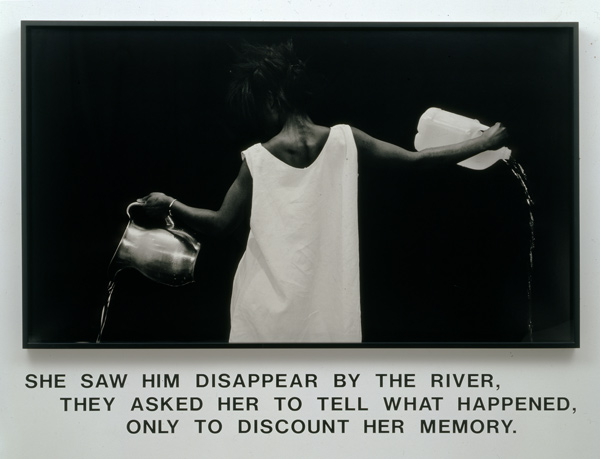

Carrie Mae Weems (American, born 1953). Mirror Mirror, 1987–

88. Silver print, 24 ¾ x 20 ¾ in. (62.9 x 52.7 cm). Courtesy of

the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. © Carrie Mae

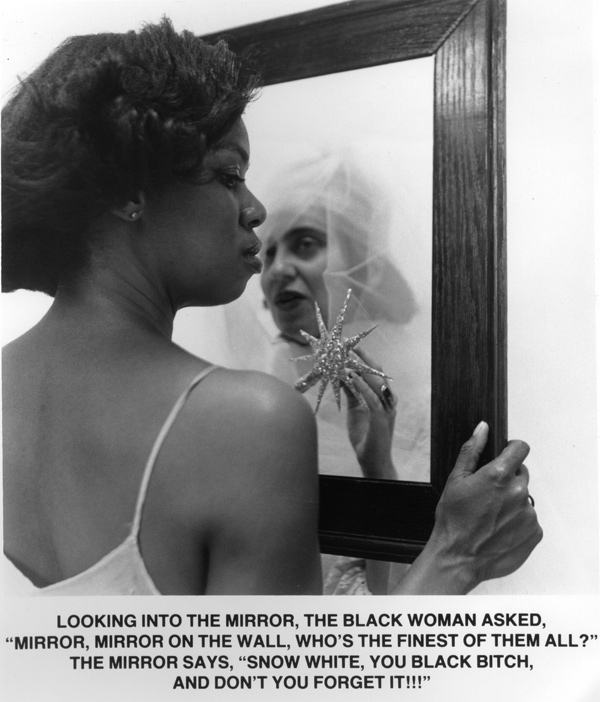

WeemsPhotographers Lorna Simpson and Carrie Mae Weems combine photos with words to create sardonically witty and moving images. Simpson’s Waterbearer (1986) depicts a young black male pouring out two jugs of water, with the words “SHE SAW HIM DISAPPEAR BY THE RIVER, THEY ASKED HER TO TELL WHAT HAPPENED, ONLY TO DISCOUNT HER MEMORY”. The piece is regrettably reminiscent of photos and reports of the murders and disappearances of young black males today, in which testimonies and footage often still lead to a not guilty verdict.

Faith Ringgold (American, b. 1930). Early Works #25: Self-

Portrait, 1965. Oil on canvas, 50 x 40 in. (127 x 101.6 cm).

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Elizabeth A. Sackler, 2013.96. ©

1965 Faith Ringgold. (Photo: Sarah DeSantis, Brooklyn

Museum)The works are not all overtly political, however, with artists like Virginia Jaramillo whose abstract expressionist paintings are on display. Other artists like Emma Amos and Faith Ringgold paint self portraits in their respective styles that do not appear particularly radical, until one realizes that to be a black woman artist, and to paint one as well, is in and of itself a radical act.

The show at CAAM refuses to be put into a tidy box. The works are sprawling, multi-disciplinary, and diverse, and most importantly demonstrate how the fixed state of art history is disputable.

“We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965 – 85,” October 13, 2017 – January 14, 2018 at California African American Museum, 600 State Drive, Exposition Park, Los Angeles, CA 90037, caamuseum.org

-

Lousy Lighting and Not Well-Hung

Clearly I am both not from LA and do not run in VIP circles because I had never heard of the Soho House prior to my invite to see photographer Kourtney Roy’s new collection of works on display there. I mistakenly assumed it was just a cheeky name for a gallery, so was quite surprised when I was invited up to a penthouse club at the top of a high-rise building in West Hollywood.

For all of the plebians like myself, here’s a rundown of what the Soho House is like. After checking in with the front desk and confirming that my guest and I were on the list, we entered an elevator with tufted plush walls to the penthouse. The entire upstairs looks like your typical restaurant/bar (think Perch in Downtown LA but with a steep membership fee), while the downstairs section has an old desktop computer and printer (amenities!), a pool table, and a large bookshelf with a disappointingly small selection of books—most of them of art. There is also an eclectic mix of art on the walls, almost all of it lowbrow, that is nonetheless well-lit with gallery lighting.

I wander around for about 20 minutes, asking every worker—who will look my way—where the Kourtney Roy art opening is. One tells me “the library” but when I ask another where the library is, she says there is no such thing. After roaming through halls past mysterious locked rooms, I eventually go upstairs for the third time and ask a different waiter where the photography opening is. He points me to a group of maybe 20 people sitting down at tables eating and drinking in a secluded part of the restaurant. It appears that some guests at the reception are eating dinner. When I arrive, I am offered a margarita—while I was lured into the situation at the promise of a champagne reception, I figured a margarita would suffice.

I ask the man working the margarita bar where the actual art is, and he points to the hallway in between the upstairs and downstairs. I look down over the balcony and see about seven of Roy’s artworks, hung without lighting, in the most inconspicuous location of the restaurant. I was, in so many words, perplexed at both the placement of the works, and the bizarre reception. The reason, then, that I chose to describe the tufted elevator instead of the art show—it’s because there was no art show. This, I found unfortunate as a long-time fan of Roy’s work. Her photographs are striking, colorful, whimsical, and have an editorial flare without feeling overly commercial. Unfortunately I was unable to see any of the works properly lit or close-up. It seems that this show was more about hanging out at the Soho House than about the art, which I find to be a let down for the work of a talented artist.

All Images by Kourtney Roy from her “California” series.

-

Radical Women at the Hammer

It’s often said that the victor writes the history, and I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that men, and society in general, have been victorious in writing an exclusionary narrative after ignoring women for centuries. Art history books, museums and other established institutions are undoubtedly lacking in female representation. That is not to mention that the women who have historically been able to “break through” and receive recognition are, more often than not, white. The Radical Women exhibition at the Hammer Museum aims to fill in some small blanks in the massive void that is Chicana and Latina representation in the art history canon.

installation view,

“Body Landscape” theme. Hammer Museum, Los Angeles,

Photo: Brian Forrest.“Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985” is wildly ambitious and impressive. The 120 women exhibited come from vastly different geographies, socioeconomic situations and personal histories. A problem frequently faced by peoples of various ethnic groups is that they are repeatedly represented in only one stereotypical way. Latin American countries with very different political and cultural makeups are mistakenly lumped into one analogous vision of a culture—a vision that is typically incorrect. And so, lazily those in El Norte project what Latin American art is supposed to look like, or is expected to look like, especially Latin American art created by women. The Hammer exhibition helps to establish unique voices that give actual shapes, actual names and actual visuals that exemplify the individuality of women working from 1960 to 1985.

All of the works in the exhibition have, in one way or another, something to do with the theme of the political body. A woman’s body is inherently political. For many people it has been, and is still viewed as an object to be sexualized: raped, plundered and eventually possessed, and turned into art by men. Most women are aware of the way their bodies are viewed by the time they reach puberty. To take proprietary rights over one’s own body and use it as a tool in one’s own art—in the way that many of the women in this show have done—is a revolutionary act.

installation view,

“Social Places” theme. Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, Photo: Brian Forrest.For centuries, women’s bodies have been represented in a limited variety of ways—the virgin, the plump and supple young thing to titillate viewers, the pregnant bearer of life and the respected matriarch, among others. By rejecting these heteronormative, patriarchal representations of women’s bodies, the artists in this exhibition present an alternate reality where women create their own definitions of themselves.

To fill the vacuum of over 20 years of Chicana and Latina art is no small undertaking, and I was taken aback by the sheer magnitude and scope of the work. I visited the exhibition again, and again, and again, and even after scouring the accompanying catalog felt like I still had more depths to plumb. I found this exciting, as the opposite is usually the case. To have the opportunity to dive into so many works by Chicana and Latina artists felt like a history lesson I had been thirsting for, from which I had previously been discouraged owing to the lack of information.

The two exhibition rooms are filled with works of nearly every medium—photography, sculpture, film, painting, drawing and experimental practices. The works are divided into seven themes—The Self-Portrait, Body Landscape, Performing the Body, Mapping the Body, Resistance and Fear, The Power of Words, Social Places and The Erotic. Mapped in this manner, the exhibition offers a natural and visually coherent path for the viewer to go down. Because of this structure, works by artists from different countries, such as Anna Maria Maiolino from Brazil and Margarita Paksa from Argentina, are placed next to each other. It’s important to note that many of the women in the exhibition did not identify as feminists, partly because they saw feminism as being closely linked to the colonialism and classism that they viewed as oppressive bourgeois forces.

Sara Modiano Untitled, 1981, from the series Desaparece una cultura (A culture disappears), 1980–84, The Sara Modiano Foundation for the Arts (this image and above images) It’s difficult to choose particular works to highlight, but there are a few that I can’t help but mention. One in particular is untitled (1981), from the series “Desaparece una cultura (A Culture Disappears)” by Sara Modiano. The series of photographs is remarkably poetic. It shows a time lapse of the ocean’s tide overtaking a red structure that appears similar to indigenous architecture of the area. After a series of photographs, the structure begins to dissolve, until eventually only a red dye stains the ocean. The symbolism of colonialism coming in from the sea to destroy structures, only to leave a sea of blood is obvious once stated; however, it remains poetically subtle upon first viewing of the series.

One work that I can’t believe isn’t in mainstream texts on conceptual art, along with artists like Marcel Duchamp and Piero Manzoni, is Sin Titulo (Untitled, 1970) by Gloria Gómez-Sánchez. The work is simply black text on a square, white background above a white table that reads, “EL ESPACIO DE ESTA EXPOSICION ES EL DE TU MENTE , HAZ DE TU VIDA LA OBRA” (“THE SPACE OF THIS EXHIBITION IS THAT OF YOUR MIND, MAKE YOUR LIFE THE WORK”). The fact that such an obviously exemplary work of conceptual art has been omitted from history is both a shame and a perfect example of why this collection of works is important.

installation view, “Erotic” theme. Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, Photo: Brian Forrest. In that same vein, Sonia Gutiérrez’ Seguiremos diciendo patria (We’ll Keep Saying Homeland, 1972) uses Pop art styling in a pointedly political and meaningful way—an aspect that was missing from much of the aesthetically driven Pop art produced by white males in America during the same period. The painting shows two brightly colored figures, presumably dead, who are hung upside down by their ankles. There is implied violence in the painting, which contrasts with the tightly rendered style.

Other impressive works include the large and impossible to overlook Epidermic Scapes (1977) by Vera Chaves Barcellos. These large, striking photographs resemble both abstract nature scenes and large prints of microscopic organisms.

Judith F. Baca Las Tres Marías (The three Marias), 1976, Smithsonian American Art Museum; Museum purchase made possible by William T. Evans Judith F. Baca’s Los Tres Marías (The Three Marias, 1976) is another standout piece, possibly because it’s so well suited to 2017’s selfie-obsessed culture. I suspect that the Hammer considered this while placing the piece near the entrance of the exhibition, making it one of the first pieces viewers see. The work consists of two painted panels of fashionably badass Latina women, and a mirror panel in the center, which I’m sure the Hammer knows makes for fantastic free advertising when museum-goers inevitably post their own selfies beside the artwork.

As far as radical acts go, I think no pieces are better than Graciela Carnevale’s Acción del encierro (Lock-up Action, 1968). The photographs document an art show of Carnevale’s, at which she demonstrated the tyranny of fascism in Argentina by locking all of those in attendance inside the gallery. The unsuspecting attendants are stuck inside the gallery until eventually someone smashes one of the windows with a rock. The attendees don’t look terribly troubled in the photos; however, I can’t help imagining how the art world’s who’s who in LA would react if a similar stunt had been pulled at the Hammer itself during the show’s opening night.

On that note, I have to wonder if the women in the exhibit would be considered for a spot in the Hammer, or any other Los Angeles museum, if they were committing such acts and creating these radical works today in response to their respective socioeconomic cultures. Are Latina and Chicana women only invited to appear in shows after their respective time has come and gone, and they are in the safe space of history where they can’t disrupt the current status quo too much?

-

Karen Finley at REDCAT

Karen Finley’s The Expanded Unicorn Gratitude Mystery unfolds similarly to a dream that makes complete logical sense when experiencing it, but is difficult to piece together the linear structure upon waking. The one-woman show lasts for an hour and a half (no intermission) and I was impressed by the endurance and vitality of the sometimes-panting, sometimes-yelling, always passionate Finley.

The performance is divided into four parts where the artist embodies four different identities, each preceded by a video except for the last section.

Photo courtesy of Theo Cote at La Mama Experimental Theater Club. The first video explicitly made fun of the art world and the lack of empirical evidence of art history. The video was definitely subtle ‘art humor’ that the audience was in hysterics over. The following act, part one, was the unicorn—a visual metaphor for complacent white supremacy wrapped up in the individualism, uniqueness and self-centeredness of the art world. While there are props and costumes on stage, most of this act, and the entirety of the performance centered around poetic spoken word.

Karen Finley as Hillary Photo by Hunter Canning The next act was the embodiment of Hilary Clinton, and was what I found to be the strongest part of the performance. Finley sharply observed the BDSM dynamics of the public wanting to ‘punish’ Clinton and have her admit that she was a very bad girl. Finley doesn’t stop there, as she muses over power dynamics, Bill and Hillary’s romantic relationship, and Hillary’s misguided resilience and ‘gratitude’, something that she seems to regard as Hillary’s downfall. During this section of the performance, the audience is enveloped in blue fabric that symbolizes Monica Lewinsky’s blue dress that had Bill Clinton’s semen on. The climax of the section is a literal one, with Finley draped in blue dresses covered in fake semen.

Karen Finley Photo by Hunter Canning In the next part, Finley embodies Donald Trump. Since the president is so easily mocked, I was curious as to how the artist could come up with a new way to analyze him. Finley concluded that Trump is the stereotypical dumb blonde that he seems so keen to objectify, and accompanies this fact with a hilarious slideshow of Trump’s face photoshopped onto the bodies and faces Ivanka, Melania, Marilyn Monroe and other famous women.

Finley as trump as let them eat cake Finally Finley appears in the last section as herself, and reads a poem on war, police brutality and other political grievances. This section was the most raw and poetic of the performance. The poem begins in an absurdist story of a woman (possibly Clinton) who gets off on war, and enjoys having sex with veteran amputees’ ‘stumps’ and ends on musings on death and dying. Finley ended the performance with an American Flag around her shoulders while taking a knee—an obvious nod to the NFL controversy. By confronting the sometimes-ridiculousness of the art world, combined with the explicitly political content of the performance, Finley is using her platform as a performance artist to possibly make change within the art world.

-

Big Art & Big Bras

Any night of openings is success if it begins with free shrimp tacos, and boy did Parrasch Heijnen deliver. The relatively new gallery, tucked away in Boyle Heights near the now-defunct Sears building, surely knows how to win over new fans. Outside the gallery, one of my all-time favorite food trucks Mariscos Jalisco was slinging free tacos and ceviche, while inside the gallery had buckets of free Modelo—yes please! There was a decent crowd out to see Billy Al Bengston’s work, but unfortunately when we arrived he had already skedaddled—he is 83, after all, so standing around all day in a gallery is presumably not his favorite pastime.

Work by Billy Al Bengston

Chiara Giovando and Carmen Argote

Argote installation art Next I stopped by Carmen Argote’s “Pyramids” opening at Panel LA, where gallery manager and curator Chiara Giovando explained that their beautiful space was artist-run with FREE RENT, which is absolutely insane. I would have been terribly happy for their stroke of luck, but I was too green with envy. They also had what looked like top-shelf tequila for free, which I unfortunately did not have the chance to try since I had to run over to Shulamit Nazarin to check out Amir H. Fallah’s “Stranger in Your Home.”

Patrick Frank and Elizabeth East

Gallery Owner Shulamit Nazarian, center.

Mat Gleason

Fellow Chosen Few Motorcycle Club member Grant Redwine with TAM Director/painter Max Presneil The opening was definitely the most ‘see and be seen’ out of the three. One of the first people I spotted was heavy-hitter painter Henry Taylor. Not long after arriving, I ran into artist Theodore Svenningsen, who surprisingly made it across town from Parrasch Heijnen in his old Ford van. I gossip a bit with contrarian Coagula Curatorial owner, Mat Gleason when Andy Moses showed up with wife/artist Kelly Berg. Art text-book writer Patrick Frank with L.A. Louver’s Elizabeth East made an appearance too. Across the room I spot Brenda Williams, Dani Tull and Lester Monzen. Just off their bikes walks in Grant Redwine and Max Presneil.

Jenette Goldstein, Aaron Noble Next to the little bar (where they served particularly good white wine) I run into artist Nadege Monchera Baer, and actress/bra maker, Jenette Goldstein with husband/artist Aaron Noble, who upon surveying my breasts, insists that they now have a store for small-chested women as well called Flattery, which in this case got her nowhere!

-

Rad Art Opening

It’s a little inside scoop that people who frequent art openings often call the Hammer openings “Hammer-ed” openings, and it’s no surprise. Armed with the (possibly) coveted “Director’s” pass, aka VIP, I was able to peruse the party without the distraction of the hoi polloi—a word, mind you, that I learned that night, which can give you some indication on where I stand on the spectrum.

museumgoers gathered around the bar The drink line was excruciatingly long as there was only one bar during the first portion, which is ridiculous—don’t they know how much people love to drink, especially when it’s free? The line ended up being a prime location for people-spotting though, which is where I saw sculptor Charles Long lounging by the balcony, multidisciplinary artist Renée Petropoulos and artist Judie Bamber.

Emiliano Gironella Parra and Jason Vass

Elena Shtromberg I’ll just go ahead and list some more A-listers to induce fully fledged FOMO for those who didn’t make it to the opening. In attendance were art scenester photographer Marlene Picard, photographer of throngs of women, Kim Schoenstadt, Lita Albuquerque, DTLA gallerists Eva Chimento and Jason Voss with artist Emiliano Gironella Parra, always-perfectly coiffed hair Mary Kelly, art historian Elena Shtromberg, Artillery contributor Scarlet Cheng and LA Times art writer Carolina Miranda, along with loads of other artists and art-world folk.

Carole Caroompas, Allison Stewart The food was not much to write home about, but I suppose I’ll write about it anyways. I was able to claw my way into getting two measly morsels—half a cheese ball and one empanada. Thank God we ran into Carole Caroompas with Allison Stewart (who graciously lent me a cigarette).

Inside Hammer

Crowds in the galleries About an hour or so after arrival, doors were opened up to the public at 8pm, and I have to say that’s when the real party started. Hoards of people poured up the stairs to get into the two large gallery spaces to see the show. The Hammer was so overwhelmed by the amount of people that security was forced to shut the door and make people wait to enter. Although, when asked, security said they didn’t actually know what exactly capacity was, I’m pretty sure the space could not hold the entire mass of people that stretched all the way down the stairs.

Jungle Fire After deciding to go downstairs and check out the fantastically-energetic band Jungle Fire, I yet again pass video artist Bruce Yonemoto who spent what seemed like the entirety of his night wandering around the Hammer grounds looking for “one of the only other Asian people here.” I really hope he found them.

Photos by Leanna Robinson