Your cart is currently empty!

Byline: Kathryn Poindexter

-

Jesse Stecklow

What does it mean for the life of an artwork when it can be experienced in dramatically different contexts, as a constellation rather than a point on a map? What happens when the legibility of a work is radically challenged by a shift in viewing conditions; do those terms become part of the work itself? Such are the questions posed by Jesse Stecklow’s exhibition “Staging Ground,” wherein autonomous works take on a double-life and exist independently as well as part of an encompassing installation.

The cultivated discomfort that this project incites stems from a socially-determined practice that challenges notions of singular authorship and the myth of the hermetic work of art; at the same time it retains some of these conventions, albeit entering them into a new visual syntax.

Upon entering the exhibition, which is dimly lit solely by fluctuating lighting elements interwoven throughout, one can feel their sensory organs becoming slowly recalibrated. The dark ambience and minimal visual stimuli heighten perception of the ticking and whirring sounds that punctuate the space.

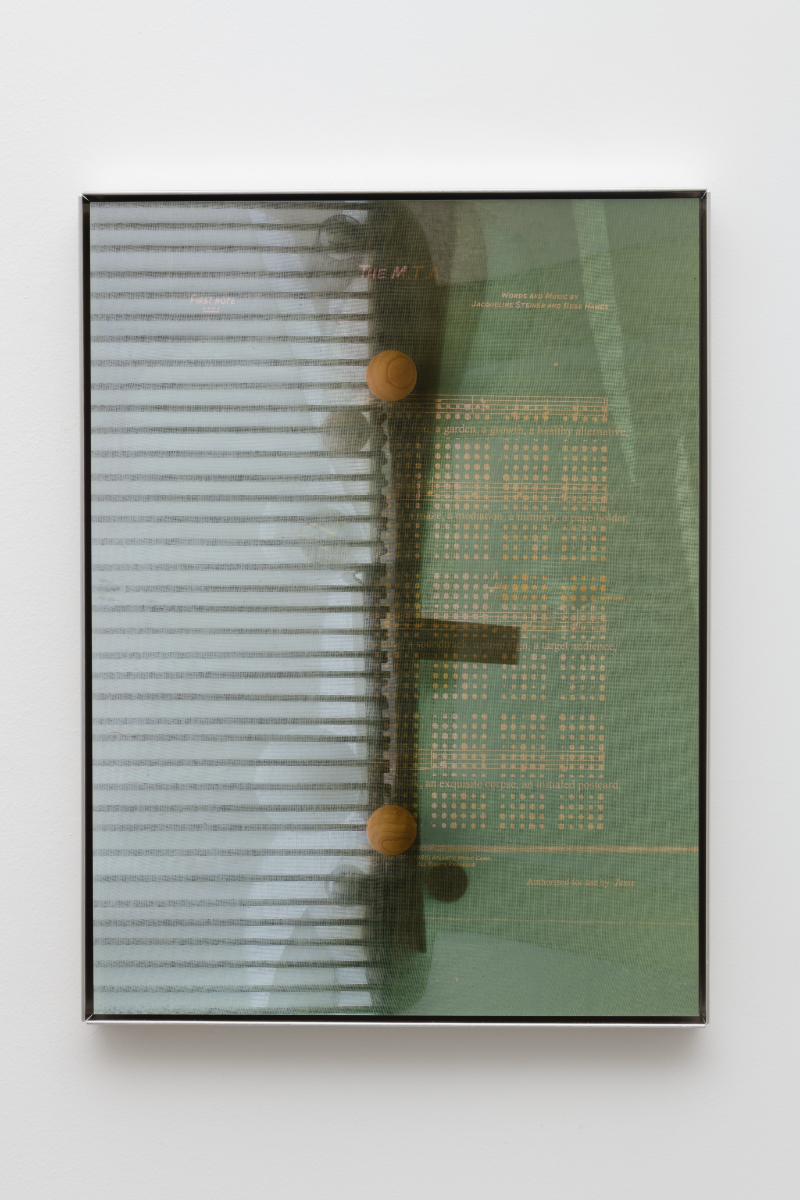

Jesse Stecklow, Staging Grounds Installation, courtesy M+B Gallery. Polished aluminum sheeting structures awash in and refracting alternating warm and cool lights dominate the exhibition and provide a sort of armature for more intimate spaces and encounters throughout. Outcroppings, perches, stages and maquettes set within this meandering structure house smaller works. Rounding the corner to the reverse side of the aluminum structure dividing the first room, one is met with a number of misplaced-looking parts and what pass as Minimalist and Dada-inspired assemblages. It takes a moment of orientation to notice the small framed inkjet print, Untitled (Parents’ Photo) (2015), lying flat on top of the shoulder-height modular ledge protruding from its aluminum armature. Moments such as this that demand that the viewer crane their neck and stoop low to get close to a work, or perambulate among components are frequent.

The composition of Untitled (Parents’ Photo) is made up of drawings of an ear set against circular marks and the image of wheat on a white background. These and other symbols recur throughout the show—ears, circles, ball bearings, aluminum, clocks, lights and found imagery relating to public transit are recapitulated into new forms. Moving in and out of sculptural, photographic, aural and ephemeral forms, it’s nearly impossible to tell where one work begins and another ends, which is very much the point. Kinetic potential, feedback loops, and the politics of public transportation are resounding themes.

The checklist accompanying the show mystifies but also offers clues. The medium information for Untitled (6:35, 18:35) (2014) lists “clock parts, packaging, carbograph 5 air samplers,” indicating that this sculpture is actively collecting airborne “data” from the exhibition space. The collection and mediation of data, processed both within and outside of art-specific contexts, is a driving property of Stecklow’s practice, and one that perpetually provides material for future transmogrifications. The authorial interplay between the artistic auteur and the network ensures that this work will never remain stuck within the confines of an established set of conventions, but also provides the maintenance of vital kernels of humanism along the way.

-

Allison Miller

Allison Miller’s oeuvre is firmly and unequivocally rooted in the painting tradition, and yet is built upon a conviction, evident in her output over the past decade or so, to explore every inch of the possibilities, conditions and inherited clichés of painting. It operates more as a dynamic, undulating continuum than a machine on a trajectory. Equally adept at inventing strategies and systems as she is at destroying and subverting them, her work’s success largely depends on the interplay and balance of the two.

In Jaw (2016), for example, Miller plays on clichéd pictorial conventions as well as “doodling,” a form of “non art” art. A blue zigzag framing device resembling a caricature of an actual frame edges the painting, while symmetrical yet imperfect curlicues sit in the top corners, suggesting the rehashed tropes of pictorialism seen in children’s art. A horizon rests tacitly in the background as if to connote landscape. Bursting forth from these motifs comes an army of vertical stripes, which at times intermingle with the other elements but generally tear through the composition with a flattening effect. Miller often juxtaposes inherited tropes with unexpected elements that disrupt our conditioned visual modes.

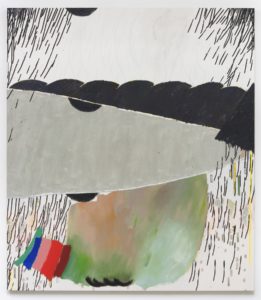

Allison Miller, Door, 2015, ©Allison Miller, courtesy of the Artist and The Pit Gallery, Los Angeles, photo by Jeff Mclane. The title of her current exhibition, “Screen Jaw Door Arch Prism Corner Bed,” is a combination of the titles from all seven works in the show. Bed (2016), a diptych and her largest work to date, occupies the entirety of “The Pit II,” the smaller room adjoined to the main gallery. Like many of Miller’s works, its syntax consists of both purposeful structural marks and those that appear more haptic and improvised. Here, more than with the other works, is a clearer delineation of the succession of the acts that contributed to the creation of the work, and more negative space left around the marks. Perhaps the traces of how the artist created this work in time contributes to its relative lack of strength in comparison to the others.

Miller’s works seem to operate most successfully when the surfaces convey a certain visual democracy, achieved at least in part by the obscuring of chronology—something she does exceptionally well in Corner (2016). It’s quite difficult to say whether she began with the foreground or background of Corner, all parts feel simultaneous. Yet ironically, this simultaneity encourages a more extended temporal experience of the work. Flat areas of disharmonious colors butt up against scatterings of more tightly-controlled line motifs. The work is simple in its basic visual vocabulary and composition but seduces the viewer with its deliciously unconventional use of color. Another highlight of the show is Door (2015), a composition split crassly into thirds. Here, gorgeously rich blacks meet fractured lines—the color palette of the Fauvists—and soft, bloated shapes reminiscent of the work of Philip Guston. These works are underpinned by their ability to let viewers vicariously live in the simultaneous pleasure and provisional quality of their creation. One gets the sense that they are, in the end, as a much of a surprise to Miller as to the viewer.

-

Grice Bench:

Don’t call me when you are rich or famous. Call me only if you are in the gutter.

Nods to the philosophical and an absurdist humor set the tone of this eclectic group show that is never short on substance. An homage of sorts to a late UC Berkeley professor, “Don’t call me when you are rich or famous. Call me only if you are in the gutter.” is a mix of emerging and mid-career artists, and although painting dominates, there are also satisfying forays into sculpture, installation, film, and photography. Mostly comprised of American artists based in California and New York, the show also includes a smattering of works by German artists Corinna Schnitt and Bendix Harms and Canada-born Jagdeep Raina.

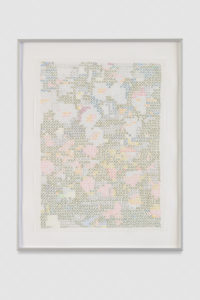

Elizabeth Ferry, Die on Pedestal (2016), courtesy of the the artist and Grice Bench. Photo by Joshua White. Here, the irreverent and playful are built on smart, often philosophical underpinnings. Elizabeth Ferry’s Die on Pedestal (2016) consists of an oversized, crudely fashioned die atop a raw wood pedestal, bearing the letters “EFIG” on the side amid glitter sparkle. The work’s playful form butts up against the suggestion of an effigy, and takes it further with the obvious double entendre of the title. Situated in relation to philosopher Immanuel Kant’s musings on wallpaper and the pedagogical value of decorative arts sits Corinna Schnitt’s Drawing 1 (2015), a small colored pencil drawing of a decorative floral motif, using only x’s as its structural syntax, as if transcribing a cross-stitch or upholstery textile. Nick Herman’s Imperial (Green) (2015), a canvas plastered in tiled remnants from an Imperial-brand commercial product, is also a nod toward Kant’s wallpaper, but does so with a decidedly pop slant.

Corinna Schnitt, Drawing 1 (2015), courtesy of the the artist and Grice Bench. Photo by Joshua White. Luis Flores’ installation Fuck It, I Guess I’m Gonna Die (2016) is a (perhaps too) literal, part-modernized take on “Buridan’s Ass”, a philosophical paradox that illustrates problems inherent to free will. Here, a clothed woolen figure donning a donkey mask stands ineffectually between two bales of hay on the floor, unable to pursue either due to the inability to make a rational decision in a situation where the incentives are equal.

Roger White, Untitled (2016), courtesy of the the artist and Grice Bench. Photo by Joshua White. A noteworthy highlight of the show is the work of Roger White, which includes a watercolor portrait of philosopher F.P. Ramsey (2016), a small oil painting of Donald Trump’s coif on a display stand in Trophy (2016), and Untitled (2016), a quotidian yet exquisitely-rendered bathroom still life pictured through the reflection of a mirror. Even without knowledge of the philosophical referents, much appreciation can be found in the formal sophistication, humor, and smart sensibility of the works in “Don’t call me…”

“Don’t call me when you are rich or famous. Call me only if you are in the gutter”, July 9-August 27, 2016, at Grice Bench, 915 Mateo Street, 210, Los Angeles, California, 90021, www.gricebench.com

-

China Art Objects:

Rachelle Sawatsky

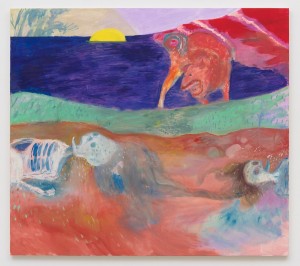

Rachelle Sawatsky’s new work in “Reincarnation Clash” (all works 2016) advances her work’s established threads of off-kilter humor paired with an experimental formal sensibility. The show consists of abstract wall-hanging ceramic works; figurative paintings on canvas; and a poem, offered as a takeaway. Beguiling and complex, and reading as if inspired by a dream or an acid trip, the poem sets a tone of playfulness wedded with introspection. One can’t help but feel disappointment in the manifestation of the show’s visual components and their relationships; the artworks don’t quite live up to the engrossing smack of the poem with which the show shares its name, and which delivers charming lines like this one: She discovers that there is no pilot/beyond the metal door and wins an award.

Rachelle Sawatsky, Interior (2016), courtesy of the artist and China Art Objects. The most enjoyable aspect of Sawatsky’s works on canvas is her adept fauvist palette and wonderfully gauche style of mark-making. At their strongest, these works evoke both the painterly pleasure and creepiness of Ensor and the naivety of Rousseau. Less satisfying are the overall compositions, which at times fall too heavily toward illustration and feel a bit sophomoric compared to her earlier works on paper, which succeed because of their rough quality and tantalizingly bizarre subject matter. One gets the general sense that the new paintings are a little too controlled, overworked, and “finished.” They conjure the psychedelic, dreamlike quality of her poem, but Sawatsky’s work operates best when the subject matter is left more ambiguous than literal.

Rachelle Sawatsky, The Animal Lover’s Guide to Tragedy/The Emotional Person’s Guide to Plot (2016), courtesy of the artist and China Art Objects. The surfaces of Sawatsky’s wall-hanging ceramics are doused and mottled with screen print ink, ceramic glaze, and watercolor. Irregularly shaped, drenched in diaphanous veils of hard-edged color and hints of patterning, these works operate in a quieter mode, but aren’t given sufficient psychic space to fully articulate themselves.

Rachelle Sawatsky, Untitled (2016), courtesy of the artist and China Art Objects.

Rachelle Sawatsky, Untitled (2016), courtesy of the artist and China Art Objects. They come off more as punctuation for the larger works than part of the show itself. Sawatsky is an accomplished colorist, poet, humorist, and draftsman, but her strength seems to lie in works that lend themselves to a less polished format than many of those in “Reincarnation Clash.”

Rachelle Sawatsky, Untitled (2016), courtesy of the artist and China Art Objects.

Rachelle Sawatsky, Untitled (2016), courtesy of the artist and China Art Objects. Rachelle Sawatsky, “Reincarnation Clash,” May 21-July 9, 2016 at China Art Objects, 6086 Comey Avenue, Los Angeles, CA, 90034. www.chinaartobjects.com.

-

M + B:

Whitney Hubbs

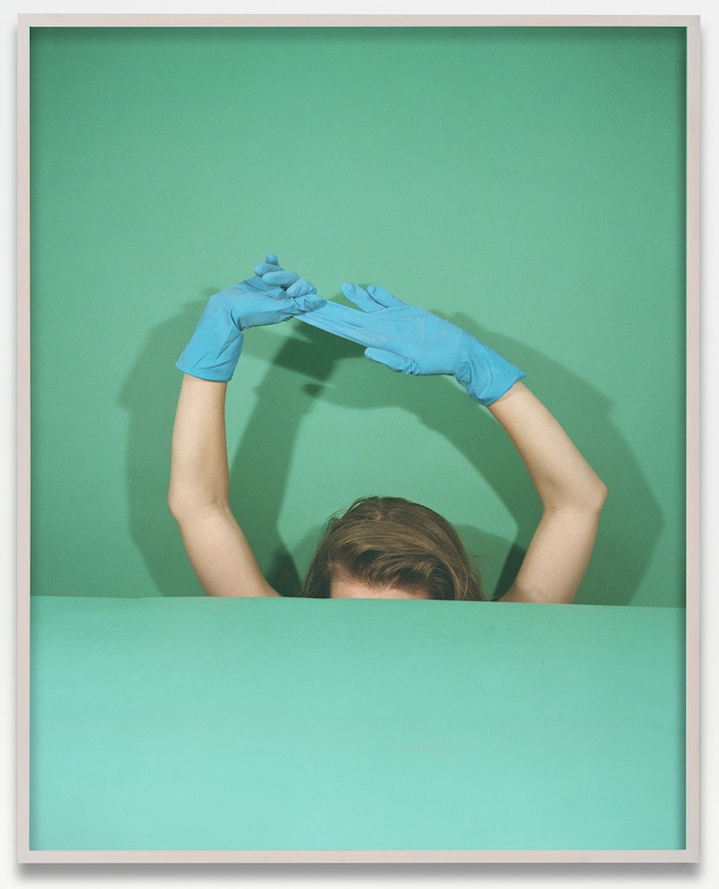

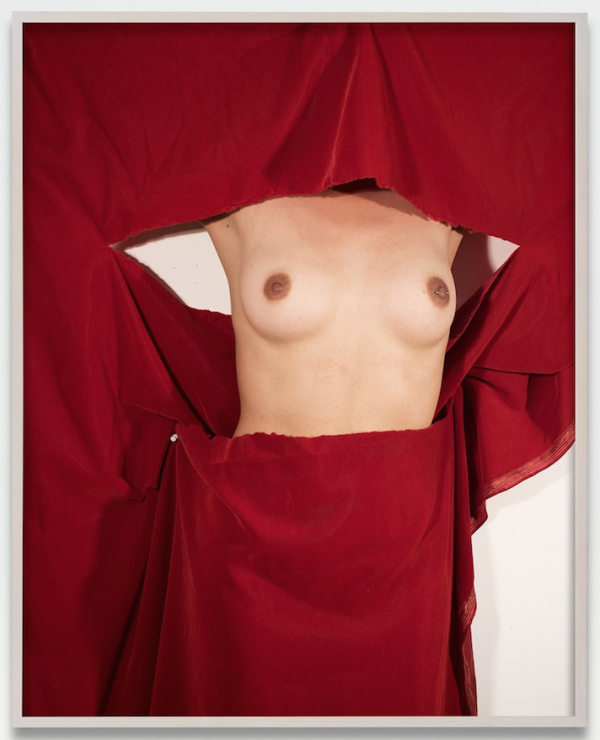

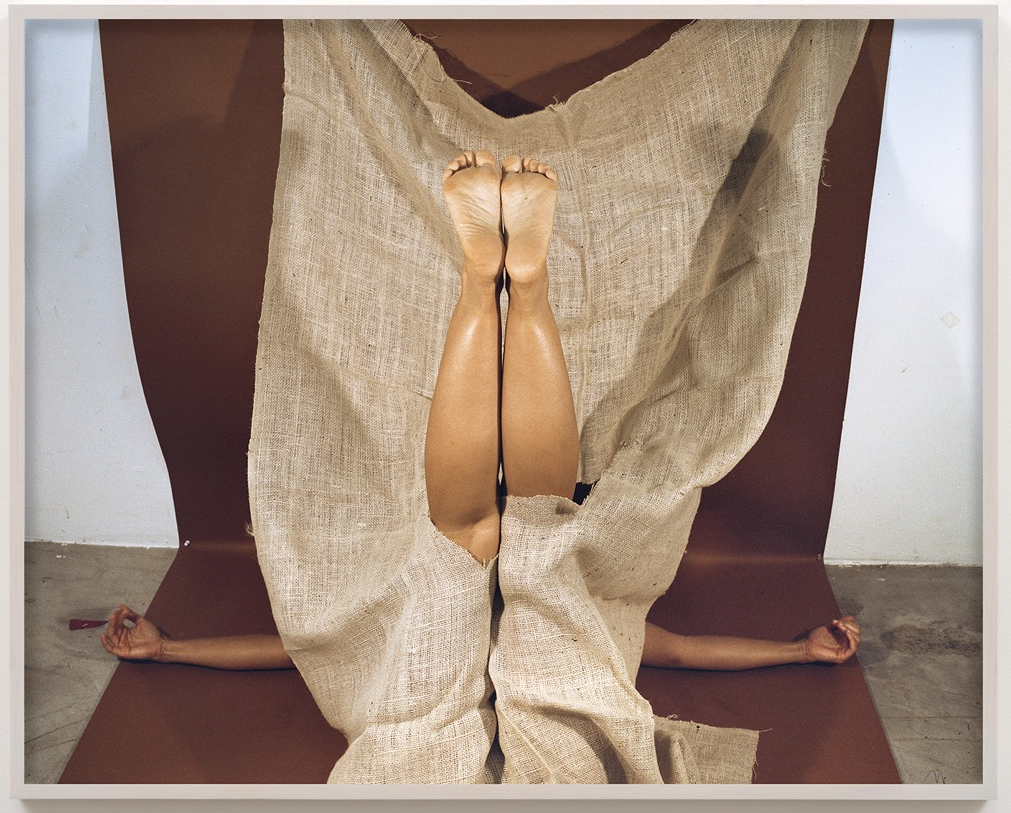

Whitney Hubbs’s “Body Doubles” presents the artist’s first attempts at color photography after a decade of working in black and white. Eleven midsize photographs feature anonymous women intermingling with provisional sets and props. These cropped and fractured limbs and torsos are, decidedly, the subjects of Hubbs’s compositions; subjects that endure both abstraction and obscurity.

Whitney Hubbs

Woman no. 2, 2016In Woman no. 12 (Self-Portrait) (2016), a very intentional red herring, we meet the vacant, trance-like stare of Hubbs herself, overexposed in a frontal, waist-up shot; the image lingers as a near-apparition. Holding her arms stolidly at ninety degree angles, her limbs become a secondary frame. This nearly-monochrome, colorless work stands in opposition to the others in the show, all of which exercise an assertive use of color that manifests in drapery, colored paper backgrounds, and improvised props. The works engage in a discourse on the pervasive relationships between women’s bodies and directorial imperatives, and on how women choose to represent themselves and each other in modes of empowerment.

Whitney Hubbs

Woman no. 5, 2016To pose is to perform the body. Some of Hubbs’s photographs conjure tropes specific to historical representations of the female nude (passively reclined, seductively baring legs and breasts). Others show the body, closely cropped or from afar, in mid-action—seemingly (one wonders at the authenticity of the “action”). An ambiguity which begs the question: is this decisive moment the artist/camera’s, the models’, or a combination of both? In the new works, Hubbs places notions of play and theatricality at the helm, but exchanges them for the mystery and magic achieved in her black-and-white works. While the new formal strategies may place her in dialogue with other contemporary L.A. photographers like Heather Rasmussen or Anthony Lepore, it comes at the price of the special brand of otherworldliness and well-honed tonal mastery achieved in her colorless works.

Images courtesy the artist and M + B gallery

Whitney Hubbs: Body Doubles runs from March 19-May 7 at M+B gallery (612 North Almont Drive, Los Angeles, 90069).