Your cart is currently empty!

Byline: Ida Safari

-

M+B: : Nathaniel Mary Quinn

Somewhere between the complex compositions of Cubism and Francis Bacon’s distorted imagery lies Nathaniel Mary Quinn’s distinct approach to portraiture. On view at M+B gallery, Quinn’s newest series looks to music as narrator. Aptly titled “Soundtrack,” the exhibition couples each multimedia work with a song that best underscores the artist’s nuanced mode of expression through disfigured portraiture. Fueled by personal experiences and universal emotions, Quinn’s semi-abstracted figures result in a signature aesthetic that hovers between painting and collage.

Nathaniel Mary Quinn, “Soundtrack.” Installation view. M+B Gallery, Los Angeles. Courtesy of the artist and M+B. Photos by Jeff McLane. Quinn’s deft handling of materials—predominantly paints and pastels—is evident in Duckworth (all works 2018). Here, Kendrick Lamar’s song pairs with Quinn’s brushstrokes and markings, which are simultaneously methodical and gestural. A painted assemblage of a man with a beak, the portrait resists an absolute interpretation by way of disfiguration. Instead, the work is layered in textures, hues, and meanings. This results in a richly fractured image that is both visually esoteric and familiar in its ability to conjure emotions.

Nathaniel Mary Quinn, What About The Way You Love Me? (2018). Oil paint, paint stick, oil pastel, gouache on canvas. 14 x 11 inches. M+B Gallery, Los Angeles. Courtesy of the artist and M+B. Photos by Jeff McLane. Similarly, works like What About The Way You Love Me? and Movin’ Down The Line function as metaphorical amalgams for the human condition, both on a personal level for the artist and collectively. The former draws its name from Al Green’s Simply Beautiful. Thick, expressive sweeps of color form the fractured imagery of a young man donning glasses, a collared shirt, and a lavender bowtie. The latter pushes abstraction even further with a deconstructed figure that combines multiple planes to form remnants of a portrait. Realistic depictions of space and dimensionality are blurred, as objects—a lampshade and foliage—linger along the edges of the frame.

Nathaniel Mary Quinn, Movin’ Down The Line (2018). Black charcoal, gouache, soft pastel, oil pastel, acrylic gold leaf on Coventry Vellum paper. 38 x 38 inches. M+B Gallery, Los Angeles. Courtesy of the artist and M+B. Photos by Jeff McLane. With abstraction often comes obscurity; regardless, Quinn’s work maintains the ability to elicit a visceral reaction to the universal truths of human experience in all of its complexities.

Nathaniel Mary Quinn, “Soundtrack,” May 19 – June 23, 2018, at M+B, 612 N. Almont Drive, Los Angeles, CA 90069. www.mbart.com

-

Ruben Ochoa

Ruben Ochoa’s “SAMPLED y SURVEYED” illustrates the artist’s penchant for transforming basic construction materials into structural installations charged with meaning. Primarily working in wood, metals and concrete, Ochoa’s referential works function as tools with which we can consider issues of social class and identity, while highlighting the artist’s interest in urban space. Despite their Minimalist appearance, Ochoa’s sculptures are contextually laden; primarily concerned with architectural and urban spaces’ ability to dictate our experiences, and, secondarily, those experiences as articulated from the perspective of a Latin American artist.

Deconstructing the exhibition’s title as a departure point, Ochoa alludes to his heritage and dual identity as a first-generation Mexican-American immigrant with the inclusion of “y” rather than “and.” To “sample” is to test and explore, as the exhibition intends to examine the natural and built environments by way of construction materials. Likewise, to “survey,” typically a function of topographic analysis, is to verify your own parameters and the parameters of those who surround you. This denotes Ochoa’s interest in urban space as an invisible social construct with the ability to control, isolate and marginalize.

Works like Economías Apíladas/Stacked Economies (2017) and Ebb and Flow (2017) speak to the social tensions found in the urban environment through their materiality and strategic placement in the gallery. The former—a nine-foot-tall stacked tower of wood pallets and pieces of oriented strand board—creates an instant confrontation between spectator and structure, as its commanding presence receives the visitor upon their arrival. The latter, dissonantly suspended over the viewer, is comprised of wood pallets and warped strands of rebar. Further activating the space, Ochoa drilled holes into the concrete floor, positioning the rebar within it and allowing Ebb and Flow to fuse with the interior.

Ruben Ochoa, Economías Apíladas/Stacked Economies (2017), photo by Joshua White While both pieces are meant to command and challenge the way visitors navigate through space, Ochoa’s choice of materials become carriers of socio-economic meaning. Wood pallets, used in both Economías Apíladas and Ebb and Flow, become signifiers to the laboring class. Contributing to and quite literally shaping society while simultaneously disregarded, here, the laboring class gets a voice by way of the materials they predominantly work with.

Homage continues to be paid to the working class throughout the exhibition, as rods of rusty rebar are covered in graphite and hammered onto paper, representative of manual labor in both form and process in Steel Life, Roman Numeral Five (2010). Likewise, in Sometimes walls occur (2009), a thick layer of concrete is troweled on paper. Void of any visible mounting device or nails, the piece lies flat against the wall, yet again suggestive of the laborer’s invisible hand.

Ochoa’s sensitive approach to and handling of basic construction materials exposes the deep-rooted ideologies within the built environment and reveals the need for a reevaluation of how closely we examine our day-to-day surroundings. Pallets, concrete, tie wire and rebar are no longer only resources associated with construction; rather, they have the power to shape our social interactions and signify the intangible.

-

Hauser & Wirth, Los Angeles: : Monika Sosnowska

Alluding to the postmodern architecture of her Polish homeland, Monika Sosnowska’s first solo show at Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles is comprised of six structural installations, which despite their rigid physicality and mass, are warped with drama, yet seem constructed without beginning or end. Working in steel and concrete, Sosnowska both highlights and challenges the concept of architectural space, creating an environment that disorients by way of vaguely recognizable architectural motifs.

‘Monika Sosnowska’ installation view. © Monika Sosnowska. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Mario de Lopez. Sosnowska seems to have adopted Minimalism’s penchant for industrial materials, yet her work separates itself through ambiguity, as opposed to the meticulous arrangement of forms typical of Minimalism. Evident in Handrail (2016) and Stairs (2016), which are self-referential by title, Sosnowska’s handling of the materials—black steel and red PVC pipe—result in warped, theatric forms. Handrail (2016) loops at varying heights, ridding itself of functionality; similarly, in Stairs (2016), practicality is replaced by a slightly spiraled, horizontally-positioned steel structure. Stripped to their foundational skeletons, these architectural elements stimulate perceptions with fragments just recognizable enough to establish a connection.

‘Monika Sosnowska’ installation view. © Monika Sosnowska. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Mario de Lopez. Dwarfing the viewer with its scale, Façade (2016) makes reference to the urban landscape of Warsaw. A tangled network of steel, Façade (2016) appears fragile, despite the solidity of the material itself. This dichotomy between that which is enduring and at the same time malleable, lies at the crux of the artist’s work. Sosnowska’s structural assemblages challenge the impression of utilitarian materials equaling permanence, support, and stability. In a clear sense, the artist’s newest body of work reflects the fragile human experience—resilient and adaptable, though in the end, not entirely invincible.

‘Monika Sosnowska’ installation view. © Monika Sosnowska. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Mario de Lopez. Monika Sosnowska, July 1 – September 17, 2017 at Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles, 901 East 3rd Street, Los Angeles, CA 90013, www.hauserwirth.com.

-

Edward Cella: : Vernacular Environments, Part 1

Exploring the dialectic relationship between environments—both built and natural—and the figures that occupy those spaces, “Vernacular Environments, Part 1” brings to light the complexities and temporality of the vernacular. A film of Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970) serves as the show’s departure point, illustrating the construction of Smithson’s earthwork as a conditional art relying on time and space for its existence, continually vanishing and resurfacing as the tide rises and falls.

Robert Smithson, Spiral Jetty (1970). Color Film. Courtesy of Edward Cella Art + Architecture. In the main gallery, the visitor is received by Stephen Berens’ photo series “All days are nights” (2013) that upon first glance, seems to be nothing more than a collection of hazy snapshots taken from one vantage point. While that is true, each work is also a multilayered photograph of varying times and days of the same landscape, evidenced in the elusive overlapping of trees, clouds, and buildings. This subtle layering of images in Berens’ series shows the ephemeral nature of time, both in how we understand the concept of impermanence and the impact of time on the landscape itself.

Stephen Berens, July 31, 2005, Afternoon, July 19, 2005 Morning, August 8, 2005, Morning, July 29, 2005, Late Afternoon (2013). Dye-based inkjet print, 24 x 34 in. (61 x 86.4 cm). From the series All days are nights (2013-2014). Courtesy of the artist and Edward Cella Art + Architecture. Adjacent to Berens’ photographs is Clarissa Tossin’s multimedia Monument to Sacolândia (2010), which takes a more critical approach. Comprised of an architectural model made of empty concrete bags, a video of the model placed in an artificial lake, and postcards of a still image from the video, the triad functions as representation and commentary on the president’s palace in Brazil’s new planned capital city, Brasília. Tossin combines elements from natural and man-made environments to address the myth and superficiality of a utopian vernacular. The artist’s upbringing in the capital city has shaped her relationship with architecture, adding an alternative and international perspective to the exhibition.

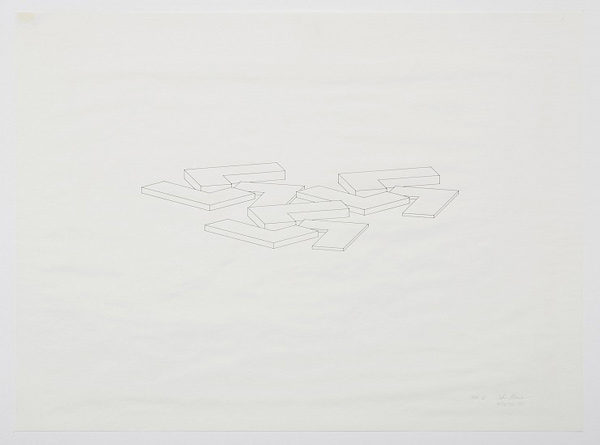

Clarissa Tossin, Monument to Sacolândia (2010). Single channel HD video, cement bag architectural model, postcards. Courtesy of the artist and Edward Cella Art + Architecture. While some pieces accentuated the natural environment, others focused on the fabricated environment, including John Mason’s Hudson River Series (1978). A collection of 10 geometric and modular contour drawings of bricks with small-scale bricks arranged underneath, Mason’s self-evident forms—slightly reminiscent of Sol LeWitt’s minimalist sculptures— confirm the wide range of what exactly encompasses the vernacular. United by the interplay of man and environment, “Vernacular Environments, Part 1” suggests the manifold ways in which the artist can engage with and respond to their surroundings.

John Mason, Hudson River Series (1978). Graphite on vellum, 18 x 24 in. (45.7 x 61 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Edward Cella Art + Architecture. “Vernacular Environments, Part 1,” May 20 – July 15, 2017 at Edward Cella Art + Architecture, 2754 S. La Cienega Blvd Los Angeles, CA 90034, edwardcella.com.