Your cart is currently empty!

Byline: Carole Nicksin

-

Tomer Aluf

FOR AN ARTIST, FINDING THE ENTRY POINT to a canvas can be the most confounding part of the creative process. Tomer Aluf, a 35-year-old Israeli who has lived in New York City for the past eight years, uses fictional narratives in which he is the protagonist as his doorway. Like an armchair Gauguin, his imaginary expeditions become fodder for his paintings.

“There’s something romantic about being alone in a studio, but in the end, you’re just alone. And you have to find ways to amuse yourself. It’s almost like masturbating, you search for a moment and you try to have fun with it,” says Aluf. Once inside the narrative and the canvas, he’s free to run with it, rebel against it, comment upon it, or whatever he sees fit. “The narrative becomes a structure, a form,” he adds.

The resulting work is semi-abstract, semi-figurative, with portions of the canvas worked out in a very painterly way, and other portions intentionally left unexplored and primitive. The juxtaposition is an expression of Aluf’s struggle with the legacy of great-artists-gone-by, and his questioning of what exactly qualifies a painting as a masterpiece. The raw parts of his canvas are about “not believing you can make a masterpiece because a masterpiece needs to be fully developed,” he says.

Continuing the theme of carving out a place for himself amongst the masters, a recent series is based on the fanciful premise of Aluf touring Morocco with Matisse. “I’m taking a trip with a successful artist who is dead,” says Aluf, a lanky fellow with an easy-going, curious demeanor. “The idea started when I went to the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. I had been painting palm trees on fire, with the pyromaniac masturbating.” But Aluf wasn’t satisfied with the look of his palm trees. “Then, I saw this painting by Matisse of palm trees, and he really knew how to paint a palm tree!” That inspired Aluf to weave a scenario that explores the idea of what it means to be a successful painter, and the idea of learning from a master. “There is something ironic there, too,” he adds.

What Aluf terms as irony comes across more like a sense of playfulness, whether it’s a girl with a strap-on staring at the viewer, or an oddly placed chicken in the midst of what seem to be body parts (executed in a style that’s equal parts Francis Bacon and Philip Guston). His paintings suggest someone who is serious about painting but at the same time does not take himself too seriously.

Aluf spends three to five days a week in the studio, pushing paint for eight to ten hours a stint. “I usually go in [the studio] around 10 a.m., and then it takes two hours to start doing something.” He also teaches art at Rutgers University and runs Soloway, a gallery in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, with three partners. Instead of viewing these endeavors as nuisances that take him away from his studio, he sees all of it as part of establishing a life in the arts.

“You make a painting and it signifies who you are,” he says. “I thought of the gallery as another representation of me. It’s another experience I can have that will add to my life as an artist. When you paint, it’s for you. When you have a gallery, it’s about other people. Even if you don’t love the work, you can still give them a chance. It’s also a great way to meet people.”

Earlier this year, Aluf took off for a real-life adventure: two months in Varanasi, the oldest city in India and by many accounts, the most intense, both in terms of poverty and spirituality. Whether or not the experience will supplant the fictional narratives in his work is unclear. He only recently returned, and is still digesting. “I want to see how it comes out in my work before framing it into words,” he says, adding, “India is crazy, like tripping on acid!”

-

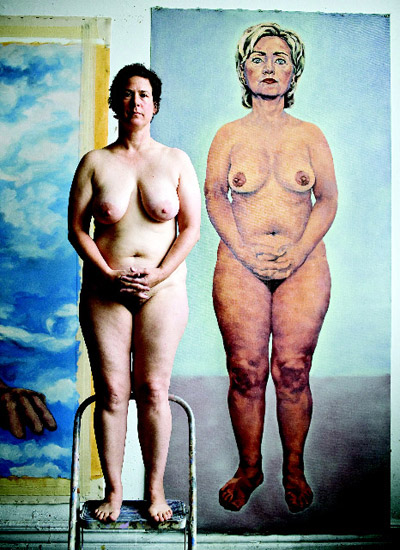

First Lady Love

It all started with a dream. “I was in a small library, and she opened the door. She put her file folders down and pinned me to the wall, kissing me,” recalls painter Sarah Ferguson. “She was so, so forthright. I found it very refreshing.”

The woman in the dream was Hillary Clinton. From that day in 2007 forward, the former presidential candidate has been the primary focus of Ferguson’s work. In addition to oil portraits, Ferguson has also created numerous photo collages, some of which can be seen on her website and in a self-published book, Hillary and I. Her obsession with the politician seems one part feminist, three parts erotic.

“Hillary is portrayed in the media as cold and calculated, but I see her as sexual,” states Ferguson unequivocally, and she’s on a mission to get others to recognize Hillary’s sensuous side. “When I read Maureen Dowd, the Hillary she concocted in her head was so different than the one in my head. In a 100 years, people might look back at Dowd’s writing and form an idea of what Hillary was like. With these paintings, I’m trying to document my viewpoint.”

In Ferguson’s East Village studio, Hillarys abound. There’s a close-up of a pissed-off looking Hillary titled “Pink Hillary,” the first of the series. “I love the expression. Those eyes! She’s so sensitive, so prickly!” Ferguson coos. A portrait of Hillary pondering a lizard shows the viewer a softer, more private side of the public figure. Yet another canvas places Ferguson in the foreground, sitting in a chair with a microphone between her legs, while Hill looks on from the background, microphone held horizontally in both hands. Ferguson painted that one shortly after the Democratic Convention. “I’m holding the microphone in my lap, away from my mouth, because my voice has been denied.”

Among these many moods of Hillary, an eight-foot-tall portrait stands out. Hillary’s face is molded in a familiar expression — lips tight, chin slightly raised, her demeanor serious and authoritative. To her detractors, this “don’t fuck with me, fellas” look might epitomize what they dislike about her. The twist here is she’s buck naked, staring you down as if to say, “What are you looking at?” Her aging flesh and sagging breasts are painted in loving detail. “I could have made her more erotic, but this is the beauty of the real. There’s no artifice. She’s stripped bare,” Ferguson explains.

Photo by Rainer Hosch On Christmas Day 2007, she posted an image of Naked Hillary on Flickr.com. “I was so involved in political blogging, and I wanted to talk about things that weren’t being discussed, like the sexism [that Hillary provoked]. Within a week, I had 500 hits.” Things continued at that pace until Flickr tagged the image at the end of February. But Ferguson was happy with the results of her experiment. “The only way to find it was by typing ‘hillary naked’ in the search, so at that moment, there were a lot of people who wanted to see Hillary naked! I really tapped into something.”

Until about six years ago, Ferguson, 43, was pursuing a career as a math professor. But shortly after she was awarded tenure at Wayne State University in Detroit, Ferguson asked for a leave of absence and moved to New York in 2002 to paint full time. She enrolled in an MFA program at the School of Visual Arts in 2006, and graduated this past spring. “Both math and painting are a search for truth, and both are a battle. I would end up with a big pile of scratch paper, trying to figure out a formula, and I must have painted over Naked Hillary five times, trying to get it right.”

Interestingly, Ferguson had one of her biggest breakthroughs working on a 7′ x 8′ canvas entitled Hardball, that depicts Chris Matthews and Keith Olbermann jerking each other off. “Since I don’t care about them like I do Hillary, I was free to make mistakes.” The violet blue tones of the canvas make it clear that the couple is watching television. “Porn?” I ask. “No, they’re watching Hillary!” Ferguson replies. Silly me.

With Hillary’s bid fading into history, Ferguson intends to continue painting her muse. In her most recent work, Ferguson put Hillary’s head on a doll’s body. “It’s a little surreal. There’s some detachment. It’s less personal. A dealer who looked at my previous work said most artists don’t work from complete identification. But I had to go through that living with her, talking to her, having her as an imaginary friend.” Ferguson sees this new Hillary as a universal mother to us all. “She’s looking down and her head is like the size of your mother’s head when you were getting your ass wiped. It’s like she is there to take care and provide and clean things up. And the heavens are there, and the sky. It’s death and rebirth. I think her role as senator will be much larger now,” says Ferguson, with a hopeful, lusty glint in her eye. ■