The desire to make drawings move goes back centuries. A 5000-year-old bowl found in Iran contains a sequence of images of a goat jumping up to a tree that could appear to be an early animation if the bowl was spun quickly enough. A 3000-year-old lamp found in China had a band that spun because of the heat of the lamp, causing the animals portrayed on the spinning lampshade to appear to move. Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man drawing implies movement from multiple angles. A book from 1634 describes a device with spinning pictures that appear to move. By the 1800s the history of animated drawings becomes more precise.

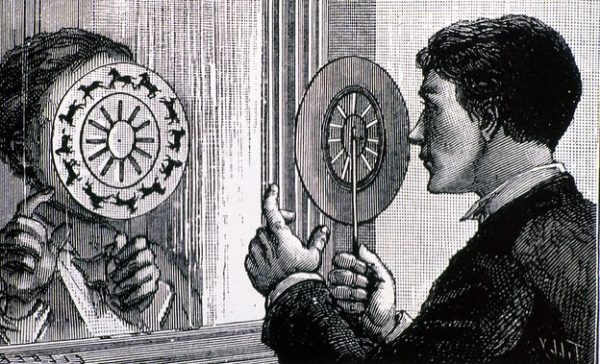

Phenakistoscope, Netherlands, c 1850

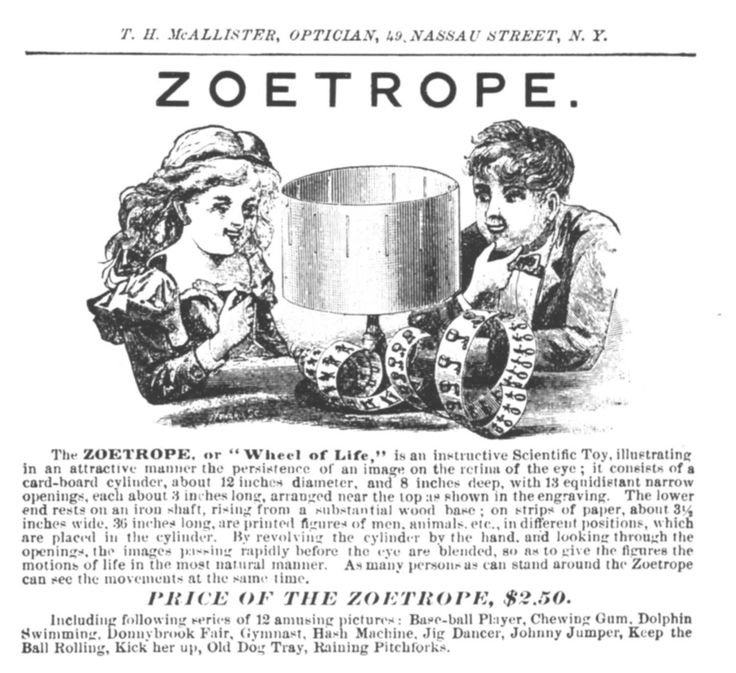

In 1833 the Phenakistiscope animation disc first appeared in a pamphlet. Between 1833 and 1865 a series of prototype zoetropes (a cylinder with slots through which the viewer sees drawing sequences printed on the inside of the cylinder, which appear to move as it spins) appeared on the scene and began using photos to create the illusion of movement. By the time the first animated short (in the sense that we now know animated films) appeared in 1906, audiences had already seen projected moving images in the form of magic lanterns. These first appeared in the early 1600s and began their life in entertainment as devices meant to scare people. By the mid-1600s ways were found to make the projected images move.

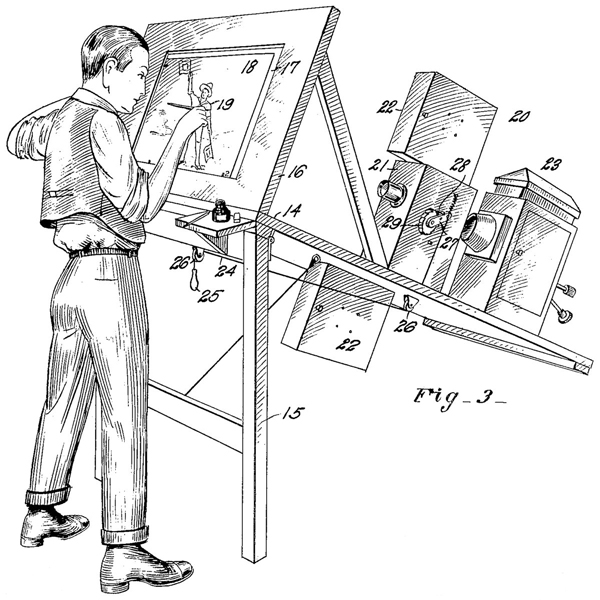

Rotoscope patent drawing

By 1914 animated cartoons began to appear in commercial theaters, but they still looked stilted and jerky. An inventor named Max Fleischer patented a new invention to fix this in 1915. His invention projected a photographic film on a glass surface one frame at a time, so that the animators could trace the photos for more naturalistic motion in animated characters. To show off his new invention, he conceived a series called “Out of the Inkwell.” (Fleischer’s studio is best known for pre-code vixen Betty Boop.) In these shorts he would let animated characters out of an inkwell and interact with them.

Zoetrope ad

The appetite for live action and drawings in the same frame made these very popular. His studio would continue to produce versions of these for the following 50 years. In the 1920s Walt Disney produced his own live action–animation hybrid with the Alice comedies. Given the global powerhouse that it is has become, it can be hard to imagine that Fleischer’s studio was once a rival to the Disney brand. (Fleischer’s early box office hits included animated versions of Superman and Popeye that still look dazzling.) By 1934 Fleischer’s patent on the Rotoscope expired, and the Disney studio was able to use it for their hit movie Snow White. Along the way, rotoscoping allowed us to watch Gene Kelly dance with Jerry the mouse, and Dick Van Dyke with cartoon penguins. More recently, Richard Linklater used a recent invention called “interpolated rotoscoping” which flattened out photographic images to look like drawings: drawings that move.

0 Comments