We tend to prize a certain class of “master” drawing above and beyond the no less essential sketches or more mechanical work; and we could probably put most if not all of the drawings in “Bridget Riley Drawings: From the Artist’s Studio”—a compact but gorgeous wunderkammer of work that traces Riley’s artistic evolution from “looking by drawing,” through academic exercises and early inspirations, to the perceptual, intellectual and artistic breakthroughs that became foundational—into that category. But there is nothing here that doesn’t touch on some crucial discovery, observation or epiphany that turned a critical key in her development.

Bridget Riley became famous during the 1960s as her work in morphing geometric abstraction became further elaborated (and pigmented) and swept up into the Op Art movement that included notably, Julian Stanczak, Richard Anuszkiewicz and Victor Vasarely. But there was always a distinct difference in Riley’s rigorous focus on edge, contour and the movement of abstracted point, line and curve—also the eye itself.

An admirer of Seurat, whose own dense tonal studies in charcoal and Conté crayon undoubtedly influenced her, she found her way back to him through landscape studies in the late 1950s, though her point -illism is looser, with a focus on massed elements more than specific figurative incident. There are some fine examples of this in the show. But the real breakthrough moment comes through as a quasi-

schematic sketch in pencil and black Conté crayon—really four essential zones: white, black, descending black horizontals like dashes, and eddying broken curved lines ascending in three directions toward the solid black field in the upper-right corner. It’s her sketched souvenir of a coastline drive with her sister: Recollections of Scotland (2) (1959)—as ephemeral as it comes—yet everything is here.

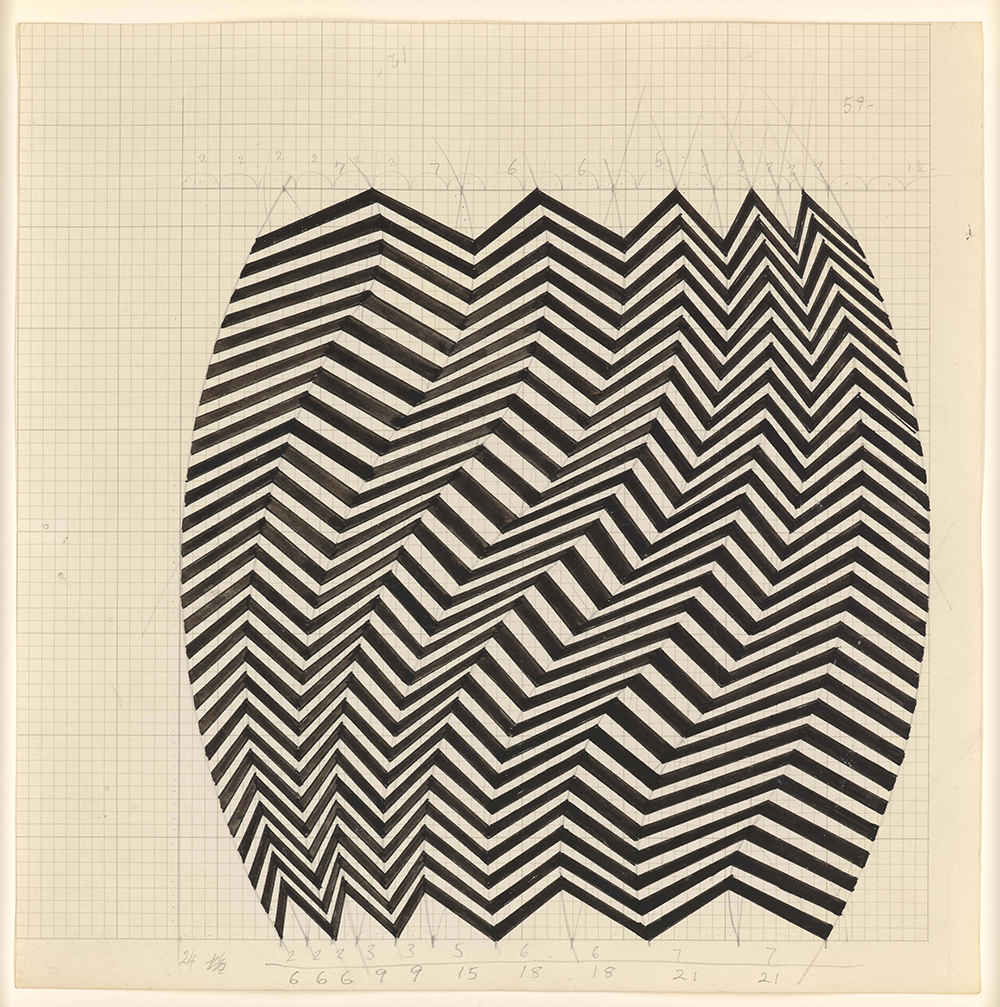

Study for Shuttle, 1964. Gouache on graph paper. Collection of the artist, © Bridget Riley. Courtesy of the Hammer Museum.

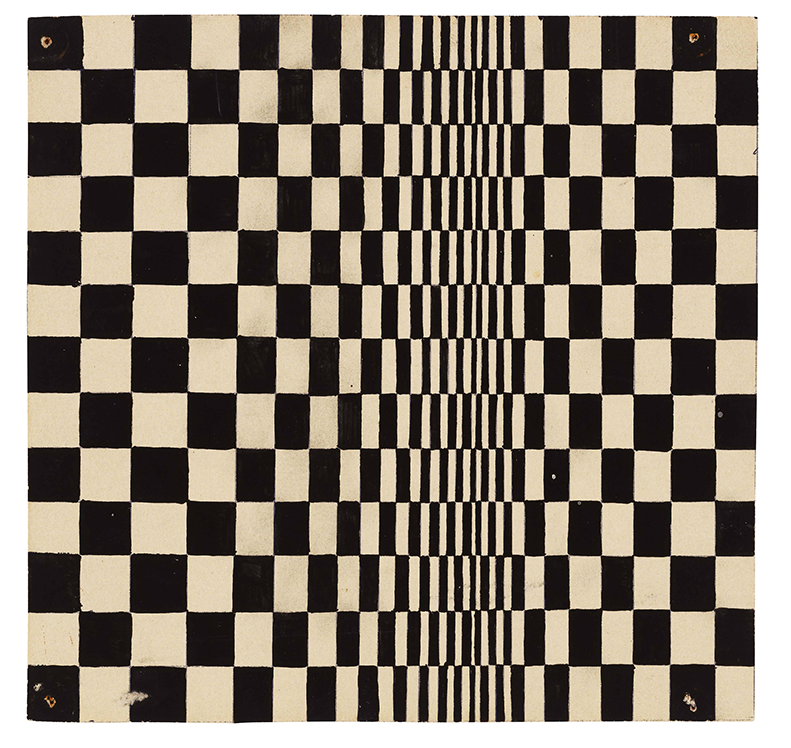

Around this time, Riley’s process becomes one of extreme distillation and refinement. Kiss and her three prismatic Untitled black circle diffractions in pencil and gouache (1961) signal breakthrough moments; and there’s a penumbral ambiguity in their reflections and refractions. It’s a short hop from this post-pointillism to the pulsation of Horizontal Vibration and Hidden Squares (1961), and again she has the patience to break it down to the moving points, as if moving in reverse—from diffracting the wave to the wave itself (e.g., her studies for Off and Shift (1963)). From this point forward, Riley moves steadily beyond optical breakdown to the movement of light itself—with increasing emphasis on tonality and decay—inevitably leading her back towards color.

Waves and stripes eventually push her in new directions (which nevertheless hearken back to her first inspirations and explorations). It’s impossible to look at her mid-1980s stripe series and not think of diffraction media, or the late 1980s and ‘90s works with verticals aggressively crossed by tessellating diagonals and not be reminded of her tonal studies and Seurat-inspired landscapes. Or certainly it is now that the curators of this show (Cynthia Burlingham, Jay A. Clarke, and Rachel Federman) have reminded us just where it all comes from.