In Brandon Landers’ debut solo exhibition at M+B, the Bakersfield-based, LA-born and raised artist delivers a collection of expressionistic and loosely narrative paintings that draw from his experiences growing up in South Central Los Angeles, yet the works retain an ambiguity that liberates them from a being a direct autobiographical recounting, leaving them open for interpretive possibilities.

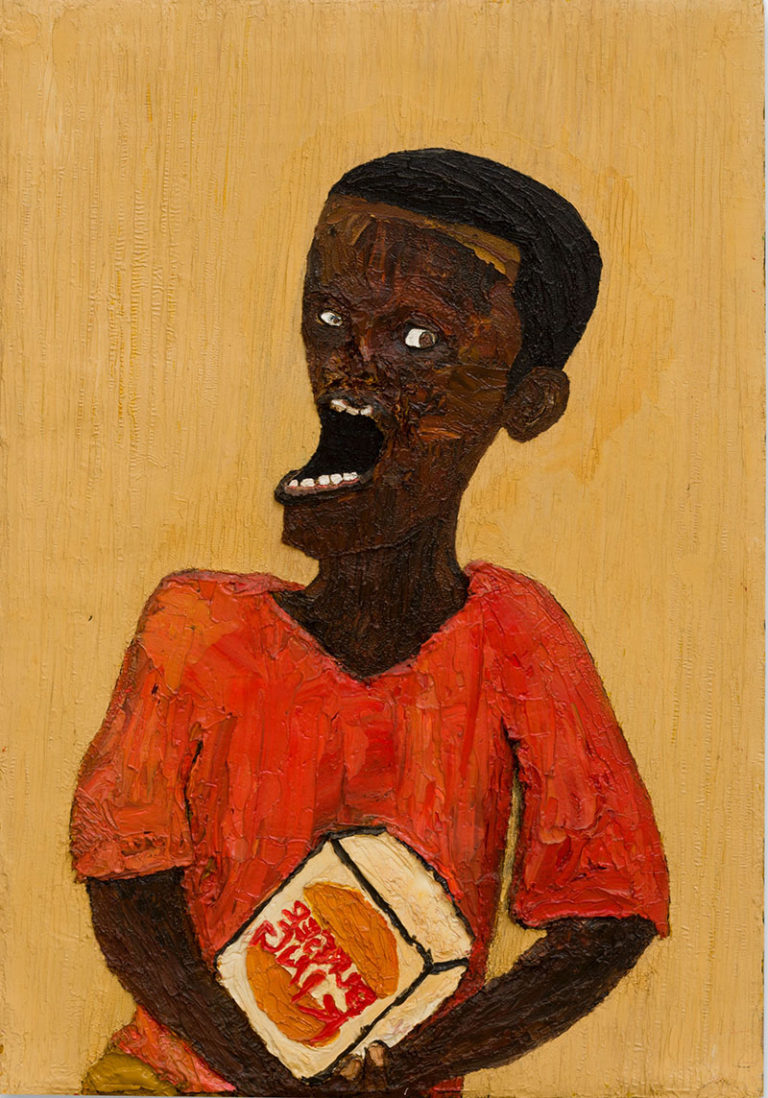

Landers works intuitively, strictly with a palette knife, which gives his paintings richly textural surfaces; he frequently scrapes—sometimes to the nub of the canvas—to reveal layers of pigment beneath, resulting in a variegated chromatic effect, in which faces, skin, clothing and grounds take on a complexity that further enlivens them.

His paintings absolutely bristle with energy and exert a remarkable presence, which is perhaps a facet of the vulnerability they signal. Landers constructs scenes with precipitous content and varied and complex relations between figures—both spatial and social. The formal qualities—the impasto, the sensuous, figured surfaces—these effects are compounded by spatial distortions, wherein figuration and facial features convey a certain “wrongness,” giving the impression that things are slightly distorted or out of whack.

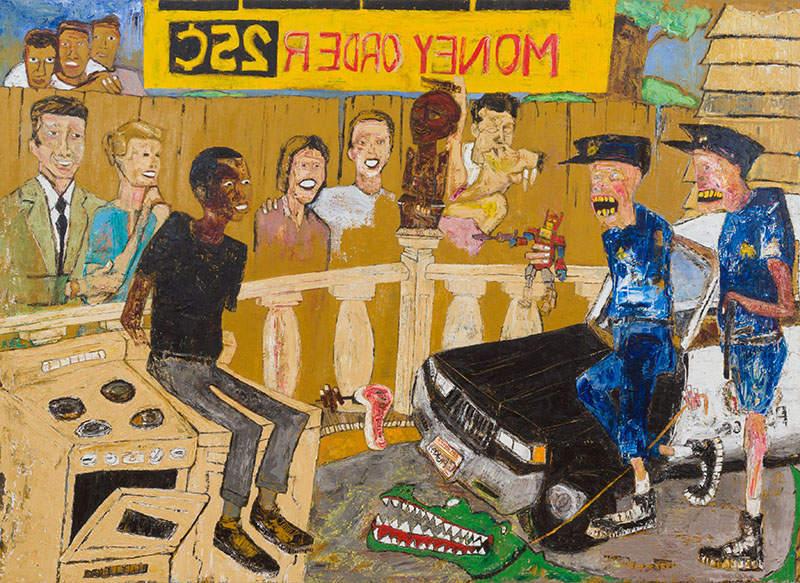

Consider these effects alongside his practice of including text or signage, in which words are consistently reversed as if the viewer perceives the scene in a mirror. These add to the representational distancing of the image from its ostensible source material—which has been distanced and refracted through the artist’s memory and imagination. Aside from the metaphorical mirroring, the formal aspect is that signs and other bits of text become graphic elements, adding chromatic and geometric verve. Compare The Joys (all works 2019) to Facin’ the World: the “Money Order” sign atop The Joys contextualizes the scene while it breaks up the figuration.

Though Landers never asserts an intention to create work that reflects the social or political climate, his deeply personal vision yields results that invariably do. In The Joys, a group of spectators looks on as a pair of boys in blue stop to interrogate a young black man. The composition of the onlookers—all white, save an African statuette, which stands as witness—place this narrative in a larger discussion of police violence against African Americans. The cops are ghoulish, their faces represented by a staccato of knife marks in pigment that conjures the reddish hue of tenderized meat. To me, these evoke images as widely disparate as Llyn Foulkes’ bloody head series from the 1970s, Francis Bacon’s terrifying studies after Velazquez’ Portrait of Pope Innocent X, and even figures from James Ensor’s Christ’s Entry into Brussels.

The pictorial aspects allow for inference about what the scene may mean, both to Landers, and to an observer. The young man’s arms inexplicably trail off and disappear. Are we to take this to mean he is unarmed? A toy transformer, which extends a weapon, is held aloft by three disembodied fingers and points toward the young man. The first cop’s arms, likewise, are not visible. Landers leaves this work and others in this collection, unfinished in places, leaving room for multiple reads.