Richard Hell swaggers up the side-walk, as if in a private movie that is being played out for the pleasure of others, as if he is being watched—which he is.

Full of himself. Happy: yes, I suppose that’s another word for it.

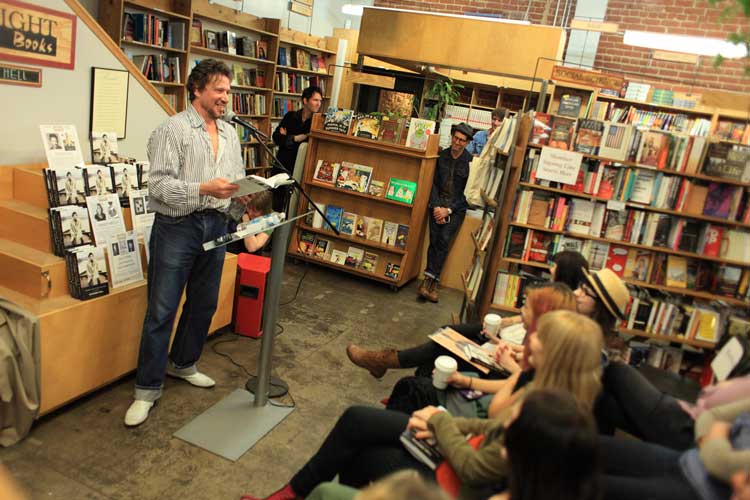

And why wouldn’t he be happy? He is about to read from his new book to a room full of people who love him: who love his work, that is—which is apparently the same thing.

And what could be more pleasant than being rewarded by the love of strangers for telling the story of one’s life and times in a memoir—I Dreamed I Was A Very Clean Tramp—that is published by a major imprint, and for which, presumably, one has received a substantial advance and is subsequently flown around the country to read from to adoring crowds.

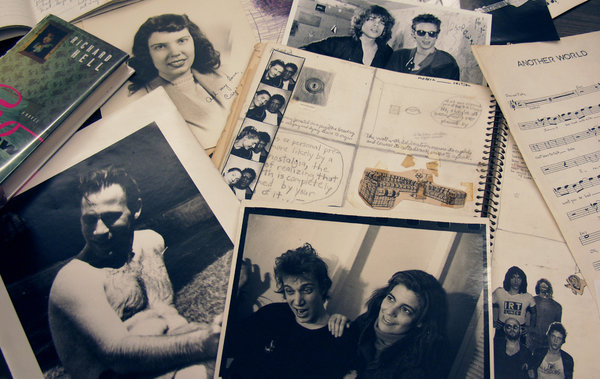

The memoir—a survivor’s tale, naturally—covers his years as one of the founding fathers of the New York punk scene: a cultural moment of such importance that anybody capable of stringing a sentence together who was even remotely “there at the time” has subsequently been inspired to commit their impressions to print; and such is the hunger—from the perspective of this sated but deprived era—for any artifact from those irresistibly heady days, that such firsthand accounts are able to ceaselessly proliferate. And why try to resist? Vital new sounds and attitudes were being forged, undiluted by virtual realities and commercial constraints. Now reality is a graveyard and those hardbitten days seem like a dream, their bones picked clean and sold back in tasteful packages to subsequent less culturally fortunate generations.

For a long time Hell’s undisputable musical and sartorial contributions seemed underrated, but nothing in the rock ’n’ roll firmament is underrated anymore, least of all anything from the mid-to-late ’70s CBGBs era. Not only was he in the right place at the right time, but he shaped that time and place, and consequently, other times and places. His position in the pantheon is secure and his memories carry weight.

Like most rock musicians, Hell’s best remembered work was produced during a brief burst of glory, and much of his later literary work (for example, this memoir, and two semi-autobiographical novels, Go Now and Godlike) are set during the halcyon ’70s. Misperceptions are corrected here, and balances redressed. Such matters as why Hell got kicked out of both Television and the Heartbreakers (see Please Kill Me, From the Velvets to the Voidoids, etc.) are finally settled at the source. Hell also ensures that his former best friend and musical partner Tom Verlaine goes down in history as a difficult asshole, although he compensates with a coda, set in the present day, in which he admits to feeling a certain sympathetic warmth towards his old friend after encountering him on the street and being struck by how cruelly the ravages of time have dealt with him, describing in perhaps overgenerous detail the former beauty’s “misshapen, larded, worn flesh.”

As in many rock memoirs, the action ends when the drugging stops. The by-now-exhausted trajectory of addiction is examined yet again: a period of time and energy that, if one is lucky and famous enough, one can feed off the memories and credibility of for the rest of one’s career. As a survivor of “the chemical life,” one can be canonized for having survived massive pleasure. It is hard not to look back upon such a raw, reckless and historically relevant youth and not feel a certain affection for who one was at the time—and Hell doesn’t appear to encounter many obstacles in that area.

As he approaches the bookstore I offer a friendly and respectful nod of recognition. He must know that somebody standing on the sidewalk outside a venue that he is about to read at is going to recognize him; there doesn’t seem to be much point in pretending to ignore him: that would be silly, especially when he is carrying himself in such a cocksure manner, as if expecting recognition.

Our eyes meet, and he looks straight through me. Never mind that we met briefly many years ago: I don’t expect him to remember that occasion (although I do remember it, in detail: an encounter with a celebrity is always indelibly impressed upon the mind of the other party) but he could at least return the welcoming smile of a friendly stranger, an obvious admirer of his work. But he just swaggers onwards, exuding an almost offensive and perhaps enviable degree of self-possession, as he enters a room that is poised to rapturously receive him.

The overconfidence crumbles once the reading begins; he sounds old and unsteady. Not that it matters to an audience who are eager to reward him for any material evidence of an otherwise mythical existence. His querulous complaints about the microphone are met with reverential laughter, as is an observation he’s quick to make about the evil, satanic atmosphere of Los Angeles: a remark that would be considered the absolute height of ignorance and condescension were it made by an Angeleno author to a New York audience.

The place was packed. I was obliged to stand behind a shelf and peer through a narrow gap between books at his left shoulder. I was now inclined towards not getting much out of the experience and left after 10 minutes.

The dilemma of liking somebody but not liking their work is all too often encountered and can make for awkward social situations. Less often one encounters the dilemma of liking somebody’s work but not liking the person who produced it, which can also create difficulties. Ultimately, however, it is usually not that one dislikes the person but that one dislikes their attitude towards one.

I should perhaps mention that these observations are based only on a cursory scanning of the book. Despite having sworn off rock bios, I was sorely tempted to read it, but his attitude saved me the trouble. I shouldn’t take it personally, of course. I’m just jealous. I envy the foundation of rock ’n’ roll notoriety that has subsequently given him freedom and exposure in other mediums. The book is probably very good. He writes well—even without the instantly expectation-lowering proviso of “for a musician.”

Had I read the book I might be able explain the origin of its cumbersome, almost unsayable title. But, as Henry James said, “Tell a dream, lose a reader.”

I DREAMED I WAS A VERY CLEAN TRAMP

An Autobiography By Richard Hell

Illustrated. 293 pp.

Ecco/HarperCollins Publishers. $25.99