Steampunk is a recent Populist art movement that glorifies unique, handmade objects and fashion from the Brass Age, an era lasting from the first large scale manufacture of nautical brass around 1830 until the mid 1920s, when automobiles no longer used brass fittings. During this time steam was the dominant source of power and machines built to take advantage of this new development tended to combine the gratuitous ornamentation of Victorian design with mechanical necessity. The machines in Jules Verne’s tales of exploration were based on these inventions and in 1954 the Disney version of Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea became the first blockbuster movie to introduce what would later be called Steampunk style by presenting the gentleman explorer as a Victorian hero. Still, the people who emulated that look didn’t form into a serious artistic subculture until the Digital Age’s straight edge forced them to become public activists for 19th-century industrial design. As critics of society they were punks, and in 1987 science fiction author K. W. Jeter invented the phrase “steam-punks” to describe them.

Some Steampunk artists eschew anything modern, subscribing to an alternate present where Victorian industrial design is still prevalent. Others honor that style, but not its mechanical and electrical inefficiencies, advocating instead the partnering up of forward scientific thinking with Brass Age tech. This is an important distinction but the philosophical camps exist together comfortably, and both ultimately recognize Steampunk as a way of life as much as an art form. As a relatively new movement it has attached itself to other trends in order to get noticed; Steampunk men and women crowd the comic conventions and even show up with brassy steam driven “autobats” at car shows.

In 2009, the Oxford University of the History of Science mounted “the world’s first museum exhibition of Steampunk”. Art Donovan, a designer and Steampunk artist, curated the show of artists that share a common passion for Victorian design and its interface with contemporary electronics and mechanics. The resulting exhibition catalog, The Art of Steampunk, is an essential guidebook to the genre and this new edition introduces other industrial designers, jewelers and artists who best exemplify Steampunk.

In most works of art, what an object appears to accomplish is more important than what it actually achieves. Filip Sawczuk’s assemblage sculptures seem to have once served as rough tools to fix an industrial machine that no longer exists and hearken back to the early primitive stages of coal-fueled steam power. Jos de Vink’s tabletop engines, made of machined brass and powered by the heat of tea warmer candles, accomplish nothing, yet their movements amuse and seem to be critical components of reality. Haruo Suekichi’s wristwatches function successfully as timepieces but their bulk makes any practical use impossible. The irony here is that the numerous scuffs and dents make it appear as though they had been used repeatedly; most Steampunk objects are presented in pristine, unused form, as if we are encountering them fresh out of the laboratory.

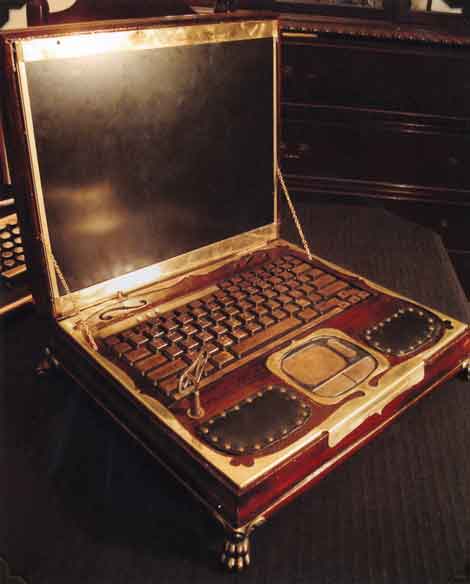

Steampunk is at its best when it presents modern tech in obsolete packaging, bringing form and function together in a successfully insistent way. Richard Nagy makes computer terminals and keyboards from old mechanical typewriters, combining the approachability of organic design with the digital age’s severity. Joey Marsocci’s Victrola Eye-Pod camouflages a USB charger in a gaudy four-footed tarnished copper stand that perfectly matches the modded iPod Nano it serves.

Then there is the wonderfully modern look of Evelyn Kriete’s Victorian fashion designs. Taking on both factory girl utility and the elegance in discipline of high couture from that period, her clothes seem to amplify Victorian self-restraint. The charms and trinkets of Amanda Scrivener (AKA Professor Isadora Maelstrom) joining materials like broken watch parts with traditional jeweler’s materials, resulting in remarkable body ornaments. Her piece, Old Camera Lens Monocle, combines leather straps with black and silver camera parts, as though built in the dungeon of a mad scientist.

As years pass and Postmodernism ages, it has become more difficult to pillage unexploited eras of yesteryear for cultural influences. The simplest and most direct styles of the past have already been mined, so all that is left are the eras of complex aesthetics and antiquated morals. But perhaps in this day and age the idea of crafting a romantic new standard for modern goods while sexing up Victorian abstinence isn’t so far-fetched; all one has to do is disregard the child labor, Imperial wars and incurable diseases of the past, the same things we ignore today.

The Art of Steampunk

Revised Second Edition by Art Donovan

Fox Chapel Publishing, 2013

ISBN: 978-1-56523-785-8

Top to bottom: Tom Banwell, Sentinel, 2010; Richard Nagy, Datamancer Steampunk Laptop, 2007; bookcover