With trunk tucked up compactly—the elephant’s sign

of defeat—he resisted, but is the child

of reason now. His straight trunk seems to say: when

what we hoped for came to nothing, we revived.

—From “Elephants,” Marianne Moore

Dick Blau uses his camera to map intersections between anthropology and photography. In his books Polka Happiness (Temple University Press, 1992), Bright Balkan Morning (Wesleyan University Press, 2002)—both in partnership with Charles and Angeliki Keil—and Skyros Carnival (VoxLox Books, 2010) he has charted the textures of life in different cultures, rooted in music, family and socialization.

Camera in hand, Blau is able to merge so completely into the flow of a scene that people drop their guard around him. In these photos we are close enough to a dancer or musician that we understand the experience viscerally, not intellectually. This ability to become an invisible witness—as invisible as anyone holding a camera ever can be—is something hard-won. For decades, Blau has been working on Thicker Than Water, an ongoing project of photographing his family in images at times startlingly intimate. In Living With His Camera, his partner Jane Gallop reports: “Living with Dick means living with his camera …Before I was living with it, I was going out with his camera—he’d bring it along on dates.”

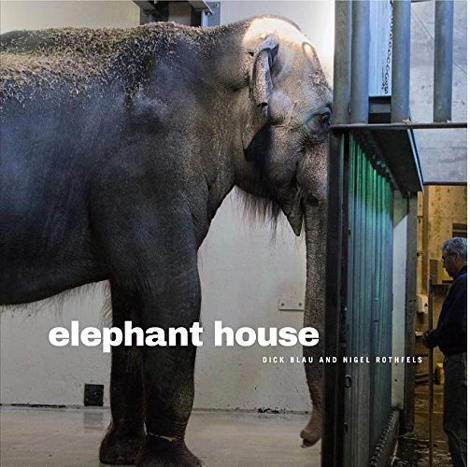

Blau’s achievement is to regard potentially sentimental subjects—family, folk customs, animals—with a steady intelligent eye that, while empathic, never urges the viewer to regard the image from a point of view synonymous with his own. This is especially so in his latest project, Elephant House, a book of photos with a short introductory essay by Nigel Rothfels. These images document something seldom seen: the relationship between animals and humans unmediated by our anxiety to absolve our guilt as regards their condition or to forge an emotional bond with how we imagine the animal. In “Why Look At Animals?” John Berger argues that animals can no longer recognize man, that we have so marginalized and commercialized other species, particularly through zoos, that they now regard us, and we them, from across an impassable gulf of damage. Blau does not argue for this or any point of view in examining these elephants and their keepers but simply allows us to watch how they function together.

Beatrice Manley, a great actress, was Blau’s mother; his father was Herbert Blau, a famous director. Theater informs Elephant House, which, more than his previous books, is staged, with pacing and blank pages indicating scene breaks. It even begins by introducing us to the cast: eight elephants living at the Oregon Zoo. This specificity is consistent with Blau’s methodology: the people in his photos are seldom anonymous. Accordingly, these photos are not just images of beasts; they are photographs of Packy, Rama, Chendra, of highly individual personalities going about their daily lives in concert with Jeb, Trina and Dimas, their keepers. (The only humans who remain nameless are those in the few photos documenting viewers at the elephant house.)

We are led through a quiet series of still lifes, objects in the keepers’ quarters: a white board with notes and schedules (“Cream on Tusko’s Tail / Full Baths on Bulls”), calendars, books (two on tying knots), photos and sketches of elephants as well as magnets and tiny figurines. (Blau’s eye for details that enclose volumes is positively Balzacian.) We are shown a full view of one of the animals; and then, with a photo of Jeb’s clenched hands above his tool belt, we plunge into a day in the elephant barn.

These photographs are mesmerizing. One of the most astonishing is of Packy, immense, primeval, his brilliant eyes watching Dimas through the bars. Mike Keele, a former elephant keeper, points out in the foreword that the barn is state of the art, designed for the elephants, not for the public. Still, it carries inescapable associations with prisons: cement floors, barred doors, impersonal corridors of grates and cement. So it is with relief that we are outside with the animals themselves and their exquisite bodies: delicate silk-like folds of an ear, a massive sculpted forehead, the weight and grace of their vast movements. The last shots are of the keepers, the space: sweeping up, gigantic feces littering the foreground; an empty cage with sawdust on the floor.

Blau’s photographs do not return us to a state of innocence with these animals. While the tenderness with which they are cared for is clear and their alert intelligence undeniable, these images haunt us because they forcefully convey how different this consciousness is from our own. Their intelligence, together with their beauty and magnificence, for a brief moment relieves us of our egoistical insistence on our imagined primacy as a species.

Elephant House

Dick Blau and Nigel Rothfels

The Pennsylvania State University Press, November 2015

$29.95