In concurrent exhibitions at Craft Contemporary, Los Angeles–based artists Beatriz Cortez and Rafa Esparza resist political declarations of border wall funding emergencies that reflect converging agendas and legacies of colonialism, nationalism, racism and capitalism. While a nation can, under these agendas, survive on and abhor the same migrant bodies of color at once—embracing their underpaid labor as necessary for capitalism while casting them as invaders subject to arbitrary deportation—Cortez and Esparza propose more liberating and sustainable simultaneities for nomadic bodies to inhabit. Cortez’ solo show, “Trinidad / Joy Station” and their collaborative work, Nomad 13 (2017 & 2019) are futuristic while incorporating Mesoamerican history. Invoking the cosmos as a metaphorical realm where borders prescribing territories, eras and identities are transcended, the artists encourage simultaneities of cultures and histories that resist linear, labor-exploiting narratives of progress embedded within capitalist modes of production and efficiency.

Beatriz Cortez, Trinidad: Joy Station (installation view at Craft Contemporary), 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles / Photo: Gina Clyne.

El Salvador-born Cortez envisioned “Trinidad / Joy Station” as a portable communal space station of the future where eclectic wanderers would find all they would need to joyfully survive, including geodesic domes, a water tower, seeds, latrines and beds. Steel undergirds much of the exhibition’s work, referencing industrialization and capitalism’s ubiquitous reach; yet Cortez leaves the steel in most works unsealed to resist the mandate to, as she notes, “perform shiny modernity.” Instead, the steel retains handprints of those who formed and handle the works, or is textured to underscore its organic qualities.

Beatriz Cortez, Trinidad: Joy Station (installation view at Craft Contemporary), 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles / Photo: Gina Clyne.

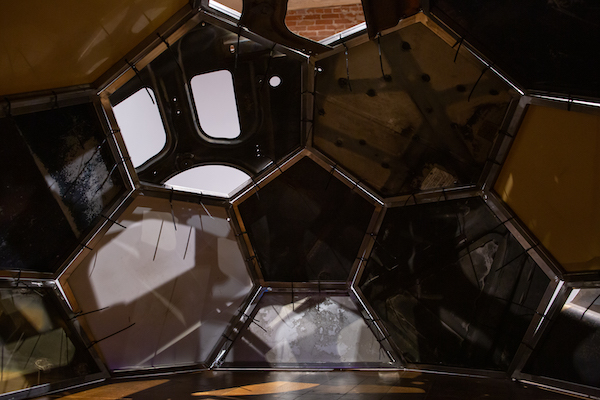

Cortez’ poetically anachronistic materiality also interweaves disparate geographies and cultures. Combining influences from the 1960s utopian artist commune Drop City in Trinidad, CO, and the ancient Mayan village Joya de Cerén unearthed in El Salvador in the 1980s, Cortez transformatively incorporates the past and present into imagined possible futures where cultures coexist rather than dominate one another. Her water tower evokes ancient Mesoamerican pyramid structures and LA electric towers, for example, while a Drop Cityesque geodesic dome built from LA car hoods is held together, like the water tower, by zip ties evoking her grandmother’s stitching, rather than in a manner boasting indestructible performance.

Beatriz Cortez, Trinidad: Joy Station (installation view at Craft Contemporary), 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles / Photo: Gina Clyne.

Cortez further transmutes materials used to detain refugee children at the U.S.-Mexico border. Often huddled on the floor inside chain-link fencing under thin emergency Mylar sheets, the children present a sweeping visual signal of urgent need, yet often remain in indefinite limbo. In weaving strips of Mylar into a petate—a Mesoamerican mat traditionally woven with palm fronds—on the ground, and through chain link into a cot and the cosmos overhead, Cortez poignantly creates a haven where children’s imaginations can soar. Through its sturdy construction and association with royalty in ancient codices, the petate offers children resilience and honor. Indirectly echoed in this work is the trauma Cortez herself experienced leaving El Salvador during a war. Her tie to Los Angeles is also referenced by chain-link fencing, which visually marks the entire urban landscape including many immigrant neighborhoods.

Beatriz Cortez, Trinidad: Joy Station (detail), 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles / Photo: Gina Clyne.

While the origin or context of Cortez’ references are preserved, boundaries between them are blurred or queered, enabling free movement. This queering occurs in the doorless conjoined latrines that blur boundaries between public and private spaces and erase the need to declare binary gender identities. Queering is also subtly referenced by the otherworldly, growth-supporting purple light over Cortez’ garden of indigenous seeds, and in the recurring motif of triangles in the structural geometry of the geodesic domes and as symbols of the cosmos. As triangles have historically condemned or empowered those labeled social “deviants” (including gay people, ethnic minorities and nomads), in this cosmic commune, all “misfits”—essentially, all of us—are widely reflected and embraced.

Beatriz Cortez, Trinidad: Joy Station (installation view at Craft Contemporary), 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles / Photo: Gina Clyne.

Rafa Esparza is also heavily invested in the terrain and people of LA. For Nomad 13, he and frequent collaborator Cortez made adobe bricks by hand with LA soil, river water and community labor, adapting the method his father used to build an adobe home in Mexico before immigrating to the U.S. Each brown brick, like unsealed steel, bears impressions of the bodies that crafted it and reflects the range of their skin tones, nationalities and ethnicities; together, they form a grounding base for a steel space capsule. Housing a garden of corn, quinoa, chayote squash and other seeds originally cultivated by the Inca, Maya and Aztec civilizations, this spacecraft carries human explorers into new territories with the aid of the portal-opening ceiba tree and Xolotl, an Aztec deity who guards travelers through unknown dimensions. Also the god of the disfigured and outcast and embodied here as a dog, Xolotl represents to Esparza the god of the queer, and a symbol of migrants and immigrants who might appear, to some, subhuman and dangerous. Basking in the same purple light that nurtures the same seeds in Cortez’ garden upstairs, this space capsule invokes its own boundary-crossing simultaneities and possible futures.

Beatriz Cortez and Rafa Esparza, Nomad 13 (installation view at Craft Contemporary), 2019. Adobe bricks, steel, plastic, paper, soil, plants. Courtesy of the artists and Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles / Photo: Gina Clyne.

In their works, Esparza and Cortez honor manual labor processes reflecting the collective resourcefulness of migrant workers who, to survive, perform essential, arduous tasks for which they often lack prior training and that others refuse to do. This generosity echoes that of indigenous people who planted seeds like quinoa to benefit future generations, sometimes at the risk of losing limbs to colonizers; Nomad 13 and Cortez’ “seed bomb,” Jumbo (2018), ensure their generosity will persist. Through “Trinidad/Joy Station,” Cortez reorients laborers’ collective resourcefulness away from survival under exploitative conditions toward joy, facilitating what she calls “collective nomadic subjectivity,” or spontaneous, integrated activity akin to cells organizing into matter.

Beatriz Cortez and Rafa Esparza, Nomad 13 (detail), 2019. Adobe bricks, steel, plastic, paper, soil, plants. Courtesy of the artists and Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles / Photo: Gina Clyne.

Cortez and exhibition curator Holly Jerger’s impromptu trip to the Bowtie by the LA River encapsulates this energy; purely for fun (and not under threat or for profit), they packed the geodesic dome panels into a car, zip-tied them in an improvised configuration for a sunset photoshoot, and disassembled and drove them back in the same day. Esparza and Cortez thus resist dehumanizing agendas, not through retaliation, but a transformative reorientation towards collectivity, fluidity, generosity and joy, alongside their simple statement as Angelenos: “I belong here.”