In case you didn’t notice, Hello Kitty invaded Los Angeles in November. If you were anywhere near Little Tokyo, you could scarcely escape the impression that not only that neighborhood, but half the population of LA’s downtown and east side had been initiated into the cult of the bow, cat-ears and whiskers. Hello Kitty has been a merchandising phenomenon for some decades now (four, to be precise: the Hello Kitty Convention that took over MOCA’s Geffen Contemporary—incredibly, all without the promotion or support of Jeffrey Deitch—was planned to coincide both with this anniversary and the Japanese American National Museum’s curated exhibition, Hello!, next door).

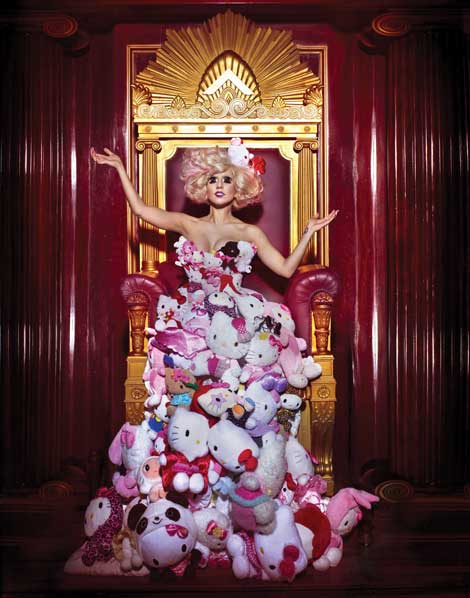

It has also become a fashion and style phenomenon, abundantly evidenced by the scene swirling in and around the Geffen. Every conceivable kind of licensed apparel or accessory was there in every conceivable combination: T-shirts, sweatshirts, skirts, blouses, sweaters, jackets, tights and leggings, shoes, sunglasses, jewelry, and, uh, bows. For the more sophisticated or thoroughly initiated among the crowd, there were variations on the traditional (or nontraditional) Japanese schoolgirl and schoolboy looks, kawaii “little Lolita” and little-boy looks, and wilder Shibuya-style improvisations. Participants took advantage of the coinciding date of Halloween to morph their “Hello Kitty” looks into a menagerie of caricature and costume far beyond the core characters created by Hello Kitty’s parent company, the Sanrio Co., Ltd. For those reluctant to dive into (and shell out for) this merchandising frenzy, there were free badges and party tiaras with the trademark bows and cat-ears.

Androgyny ruled this domain. It was amusing to see how readily every kind of merchandised apparel was picked up and worn by both sexes. As you walked around Little Tokyo and beyond into the Arts District, you saw the cardboard tiaras and their bright red bows everywhere, worn not just by children and their parents, but men and women alike. The ethnic diversity of the crowd was also remarkable. It wasn’t surprising to see masses of Japanese and Korean faces here; but it also looked as if half the east-of-the-river neighborhoods showed up, too. I can’t say I wasn’t amused to see so many ‘boys of the hood’ (or the Heights?) blithely strolling around in their cardboard tiaras and maybe one or two other bits of Hello Kitty regalia.

The masquerade of social anxiety has been at the core of consumer culture and merchandising strategy practically since the dawn of trade and commerce. But the Sanrio designers and executives took this strategy several steps further—subverting the element of anxiety by graphically emphasizing its notional absence. The Hello Kitty “character” has no mouth. It’s a self-contradictory phenomenon—a blurred icon; more specifically, the mask that fits every consumer.

Sanrio didn’t stop there; they created a back story/mythology for the mask/icon, which they exported to England. Little Kitty White went to school just outside London, where her favorite subject was English. Why merely mask an identity (or an anxiety) when you can entirely offshore it? A back story or mythology also means that there are additional characters/icons available to distract/displace and sell. If Hello Kitty is actually a little girl, it’s perfectly plausible she might have a cat, Charmmy Kitty. And wouldn’t you know that Charmmy Kitty has a pet hamster, named Sugar? And there are more.

During the mid-1980s, when Japanese economic and commercial power reached its zenith, there were frequent references to the corporate kagemusha or ‘shadow warrior’ (usually Japanese, but occasionally other nationalities), deployed in pursuit of global corporate, commercial or real estate acquisitions. This was itself a reference to the 1980 Kurosawa film, Kagemusha, which was based on historical events leading up to the Battle of Nagashino. The story turns on a pardoned thief’s resemblance to and imposture of a provincial war lord (daimyo). It is a story of anxiety, transgression and masquerade at every level—social, sexual, psychological and political.

In its 40-year reign over the kingdom of cute, Sanrio’s Hello Kitty has proven the ultimate kagemusha. She silently excuses our embarrassment at this absurd and unequal exchange. She dismisses inconvenient questions (‘oh reason not the need’). Desire and satisfaction are beside the point here; all that is required is acceptance and acknowledgment of her perfect embodiment of cute. She does not bother or bewitch us; her domain, our response, is sheer bemusement. There there, kitty kitty.

“Hello! Exploring the Supercute World of Hello Kitty”

Japanese American National Museum

through April 26, 2015, janm.org.