In March, an invitation to view ceramic work by New York–based artist Patrice Renee Washington brought me to Richmond, Virginia, for the very first time. A midsize Southern city often referred to being as far north as one can get until one is in the North, Richmond’s reputation preceded itself. When I informed friends about the impending trip, they were quick to remind me that it was once the capital of the Confederacy and, until a few years ago, had the distinction of containing more Confederate monuments than any other city. An unspoken “tread lightly” was implied.

My visit coincided with the annual conference of the National Council on Education for the Ceramic Arts. Local art institutions and galleries in and around the arts district planned for the moment by exhibiting ceramic and clay art. Walking from my hotel en route to the Institute for Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University, I noticed glints of glazed cerulean and azure through a storefront window. This was the 1708 Gallery, a nonprofit arts organization that was exhibiting beautiful and thoughtful ceramic work by young Black artists Murjoni Merriweather, Jermaine Ollivierre, LaRissa Rogers and Angelique Scott. The show was organized in conjunction with the NCECA conference and was well-situated just a few blocks from the hotel where scores of conference attendees were staying. As I spent time with the vessels and busts and strategically broken wares on view, the gallery enjoyed consistently healthy foot traffic from conferencegoers, whose bustling presence breathed life into the surrounding area.

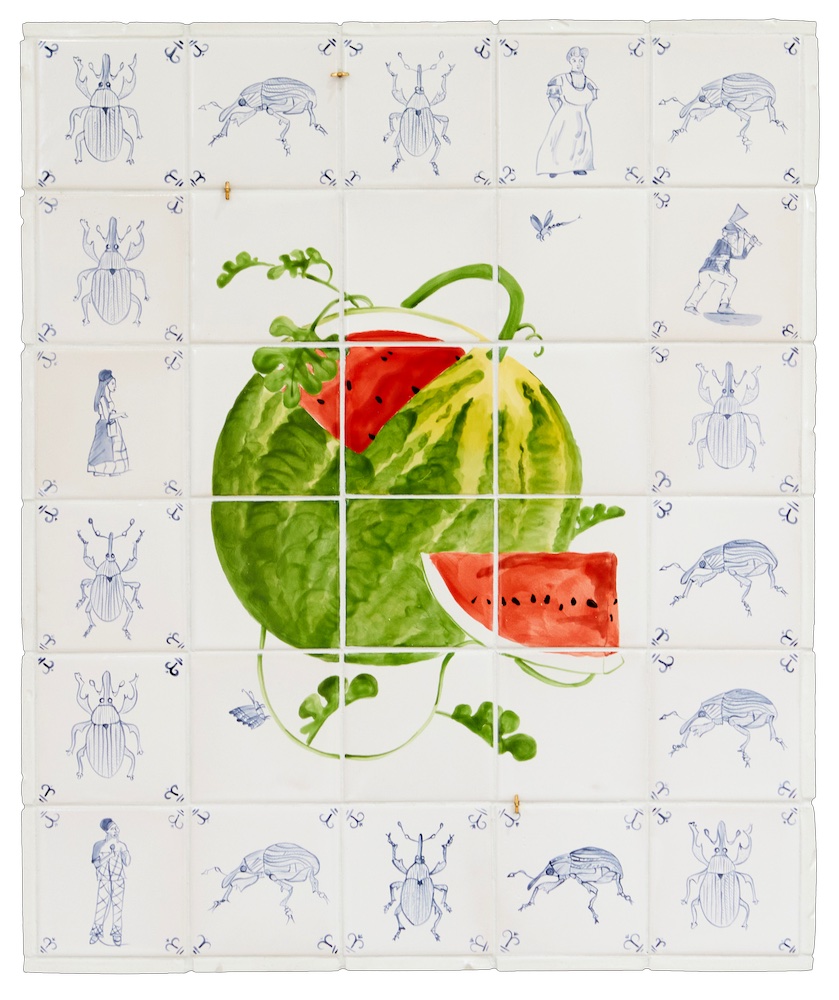

Patrice Renee Washington, Tendersweet, 2023. Courtesy of the artist and Marinaro Gallery, New York.

The Black History Museum hosted an NCECA Multicultural Fellowship Exhibition titled “Coalescence,” which is on view until August 17th. My schedule didn’t allow me a visit in person but I reached out to their staff to satisfy my curiosity. This is the cultural institution that has been given stewardship of 14 of the aforementioned Confederate monuments that have been removed from the city. In a conversation with BHM’s Executive Director Shakia Gullette Warren, she confirmed that they are partnered with The Valentine museum, located farther east in the arts district, right next door to the former White House of the Confederacy, which is now a national monument and museum.

BHM and Valentine have jointly hosted surveys and public meetings about the future of the Confederate monuments, and according to Warren, many of them are destined for an exhibition here in Los Angeles—a project helmed by LAXART and the MOCA Geffen, tentatively slated for Fall 2025. I am of the opinion that, because America hasn’t truly atoned for participation in chattel slavery, the least we can do is recontextualize these symbols of white supremacy. The spectrum of what gets molded by hand into 3D form and then celebrated is vast. The city where Confederate “heroes” were once publicly exalted is now actively elevating the handiwork of Black artists, and it didn’t feel performative.

Patrice Renee Washington, Representational image. Courtesy of the ICA at VCU.

When I arrived at ICA at VCU, I had a chance to talk at length with midcareer ceramicist Patrice Renee Washington, who was in town to give an evening talk about her exhibition titled “Tendril.” I enjoyed an enlightening walkthrough with her as she gave greater context to her tiles, vessels and sculptures. My point of view is that of a Black woman from Texas who has had to navigate overt cultural racism since birth—so it took a minute before I had a name for what I was experiencing while viewing her work. Quite simply, it was jarring, in that the vessels, tiles and installations are not overtly provocative at all, not seeking to assert or defend or confront. They were the result of the artist’s cultivated relationship with her own Blackness, resulting in sculptural clay works of quiet yet firm celebration that decenters the consideration of the white gaze.

For instance, she refers to her pieces such as Jade Flare and Onyx Hut as “energy vessels”: artifacts of a world where Black women have never suffered colonial violence, their cultural dominance and influence taken as matter of fact. The recurring motif of braids and Bantu knots on and around these vessels aren’t likely to be easily recognized by non-Black viewers. Overall, her work romanticizes quotidian markers of Blackness, making for an exhibition that’s rich with inner life, inviting inquiry that may never be fully answered, and that’s okay. It’s reparative to not have to expend energy constantly explaining oneself.

I think about how Rumors of War, a colossal bronze statue by celebrated Black artist Kehinde Wiley, stands resolutely in front of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. This monument to Black male humanity was placed in direct rebuke to the images of secessionists that were worshiped up and down Monument Avenue in Richmond, before they were removed. My impressions of Richmond are limited only to my experiences of the arts district and the small businesses and galleries there during a 48-hour visit. But aren’t the arts usually the arbiters and harbingers of greater societal change? If you want to understand where the world is going, I often say, look to the artists who are communicating with us, the institutions who are elevating them, and the money propping up said institutions, whether for craven financial gain or not. Like history itself, it’s all quite messy, and the most we can hope for is an honest effort at doing better, even on a small scale. I think that if Richmond continues to let their arts sector lead the way, then the city is bound for a long-overdue redemption.