After German reunification the remains of the famously incinerated Reichstag were first Norman Fosterized, then draped by Christo and Jeanne-Claude, and finally repurposed as the Bundestag—the lower legislative body of German government roughly equivalent to the U.S. House of Representatives. Across its Greek Revival entablature, above the Corinthian columns but below its figured pediment is written the proclamation, Dem Deutschen Volke, (To the People of Germany) a 1916 dedication of the building to the German people. This sort of revivalist architectural pantomime is common for civic structures. It compares (insert your country/city here) to the great civilizations of the past, the Greeks, the Romans, the Egyptians and accounts itself their equal.

Inside the Bundestag, at the base of its towering atrium, rests a narrow but lengthy indoor plot of shrubbery, a bit of the outdoors brought indoors. This is not uncommon in federal, state, and municipal buildings; it is aspirational. Chicago’s motto is Urbs in Horto, (City in a Garden) a tribute to its parks, lakefront and incessant tree-planting. The city was consecrated in 1837, only to burn to the ground in 1871. These mottos, these proclamations allow the cities and buildings to speak for themselves, in the proud voice of the people. But who are these people?

The Reichstag building seen from the west. Inscription translates to “For/To the German People”

The long verdant patch in the Bundestag is covered with flowering plants from all over Germany. Parallel with the ceiling and glowing with white neon faces tall black letters grow upward in the same font as the building’s pediment inscription, but this time spelling out Die Bevölkerung, 2000 (To the Population). It embraces all those who reside in Germany: Jews, Muslims, Africans, Asians, even refugees from the Americas. It is an elevated canal, a flowerbed, a mass grave, and a wonder, and also a needed corrective because the word Volk(e) has a long and troubled history.

It is equivalent to race. It is a blood and soil code word to the German born and bred of German exceptionalism, and suggests the festering Germanic fever dream of Wagnerian fantasy, a people of racial purity, a people uber alles; hence the Nazi era slogan, Ein Volk, Ein Reich, Ein Fuhrer, (one people, one empire, one leader). Yet octogenarian artist and provocateur Hans Haacke is a courter of trouble and has built a career on discomforting the comfortable. It was his social justice artwork that led to his Guggenheim exhibition being cancelled 49 years ago, although his dyspeptic fist-shaking exhibition at the New Museum was able to finish just under the pandemic wire. It included his Gift Horse (2014), a skeletal stallion holding a stock-ticker, demonstrating the intoxicating worldwide pastime of economic inequality (in German gift means poison).

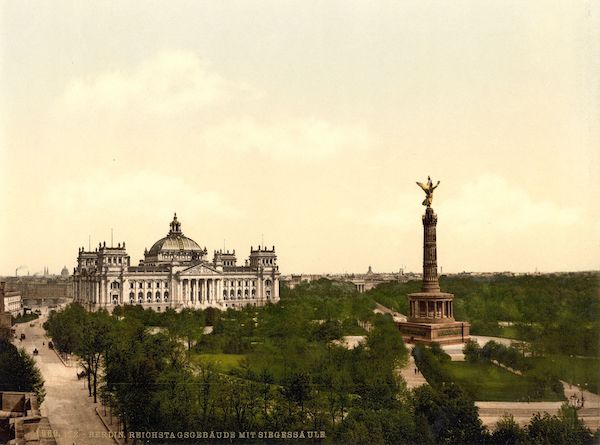

The Reichstag building with the Victory Column on the Königsplatz, c. 1900.

This virtuous plea for inclusivity, Die Bevölkerung, was (and remains to some) a controversial and contentious work. The fractious parliamentary argument—more representatives attended than for debating German peacekeepers in Kosovo—ended favoring Die Bevölkerung by the barest possible margin; 260 aye, 258 nay. And that was 20 years ago. In 2019, there were over 22,000 hate crimes in Germany.