The practice of selling art presumes severability. To sell a work from the white walls of a studio or gallery promises a degree of independence: this piece will appeal in another room, at another time. In this way a gallery is an anti-ecology. Its elements do not depend on one another—indeed, they are anxious to be separated. The old notion of artistic genius requires a similar anti-ecology. It identifies a genius as an individual whose gifts are not related to the accident of their environment. But in recent decades these assumptions have proven treacherous: in a politically sinister and ecologically frail moment, few artists have the privilege to consider themselves as fully independent of their environments—or to make work that obscures its roots in the political present. But how, in such an anti-ecology, and in relation to an object made in service of severability, does an artist represent a historical realization of dependency and interconnection?

Hayley Quentin, Myth #1 (2018). Courtesy of the artist.

For artists of “Vibrant Matter,” a charming group show at Inglewood’s Beacon Arts Building, the answer lies in work that deftly disrupts the figure/ground relationship. Downstairs, Hayley Quentin’s Myth series offers a set of male nude oil paintings whose instability threatens to bring the patriarchal body into the visual language of a queer chthulucene: scornful, discolored bodies verge upon dissolving into quinacridone red and ultramarine blue undertones. Upstairs, Jung Yun’s Waves paintings push common background geometrics, phrased in swatches of sky and .png checkerboard, to the foreground of a swirling gel impasto. Christopher Jun’s large paintings balance riotous textures with dramatically framed faces, and Elí Joteva’s Mnemoawari (2017), a dangling ball of frozen organics whose melting overwhelm the comically inadequate bowl beneath, emphasizes the messiness of some figures—to be ground is always a kind of labor.

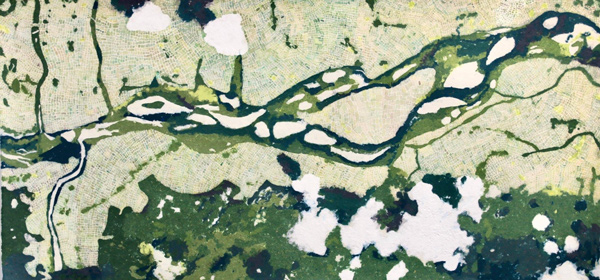

Richelle Gribble, Growth by the River (2017). Courtesy of the artist.

Elsewhere, a virtual reality work, Ben Vance and Kate Parsons’ Vibrant Matter (2018), invited viewers to hurl feedbacky figures into a stained-glass sky, and organizer Richelle Gribble’s pulp-painting series “On Place,” translations of aerial photographs into vast fields of green and white, complicates assumptions about pictorial space and abstraction. In Jonathan Fletcher Moore’s spare (not mine), 2018, a car tire—guided back and forth by an internal weight-shifting mechanism—spent the entire opening reception rolling headlong into the wall. By evening, the resulting row of faint skids suggested some of the violence in unexamined figuration—in the certainty that forms are independent of domains, and ought to rule them.

“Vibrant Matter,” August 4 – 31, 2018, at the Beacon Arts Building, 808 N. La Brea Avenue, Inglewood, CA 90302. beaconartsbuilding.com