What do CNN chief international correspondent Clarissa Ward, three-time Adult Video News All-Girl Performer of the Year Charlotte Stokely, and art-world rising star landscape painter Emma Webster all have in common? They’ve all posed for Zak Smith.

The Ward portrait was one of his earliest works, back when her hair was riot grrrl red instead of Peabody-winning blonde, the commissioned portrait of Webster—thigh-highed and holding a Diet Coke in front of Smith-ified renderings of Webster’s work—hangs proudly in the glass-fronted office attached to her cavernous Boyle Heights studio. Stokely’s painting—in front of her shoe collection—hangs, of course, in her bedroom.

Smith’s portraits range from sexy to sexualized to simply having sex. For 20 years, Smith’s gaze has been unrepentantly male and women continue to unrepentantly want to see what they look like through it.

Not everyone just wants a painting of themself—transgender porn icon Bailey Jay asked Smith to paint her “a slut who is vaguely a poodle and has something in her butt.” Smith himself admits his might seem a bit of a lowbrow assignment for the artist who came to prominence after making the 750 Pictures Showing What Happens on Each Page of Thomas Pynchon’s Novel Gravity’s Rainbow (2004) that were shown at that year’s Whitney Biennial “but not,” Smith adds “to anyone who has actually read the book.” Like Pynchon’s hallucinatory, sex-and-death-obsessed avant-garde prose, Smith’s work tends to collapse traditional notions of high and low, of the intellectual and the perverse.

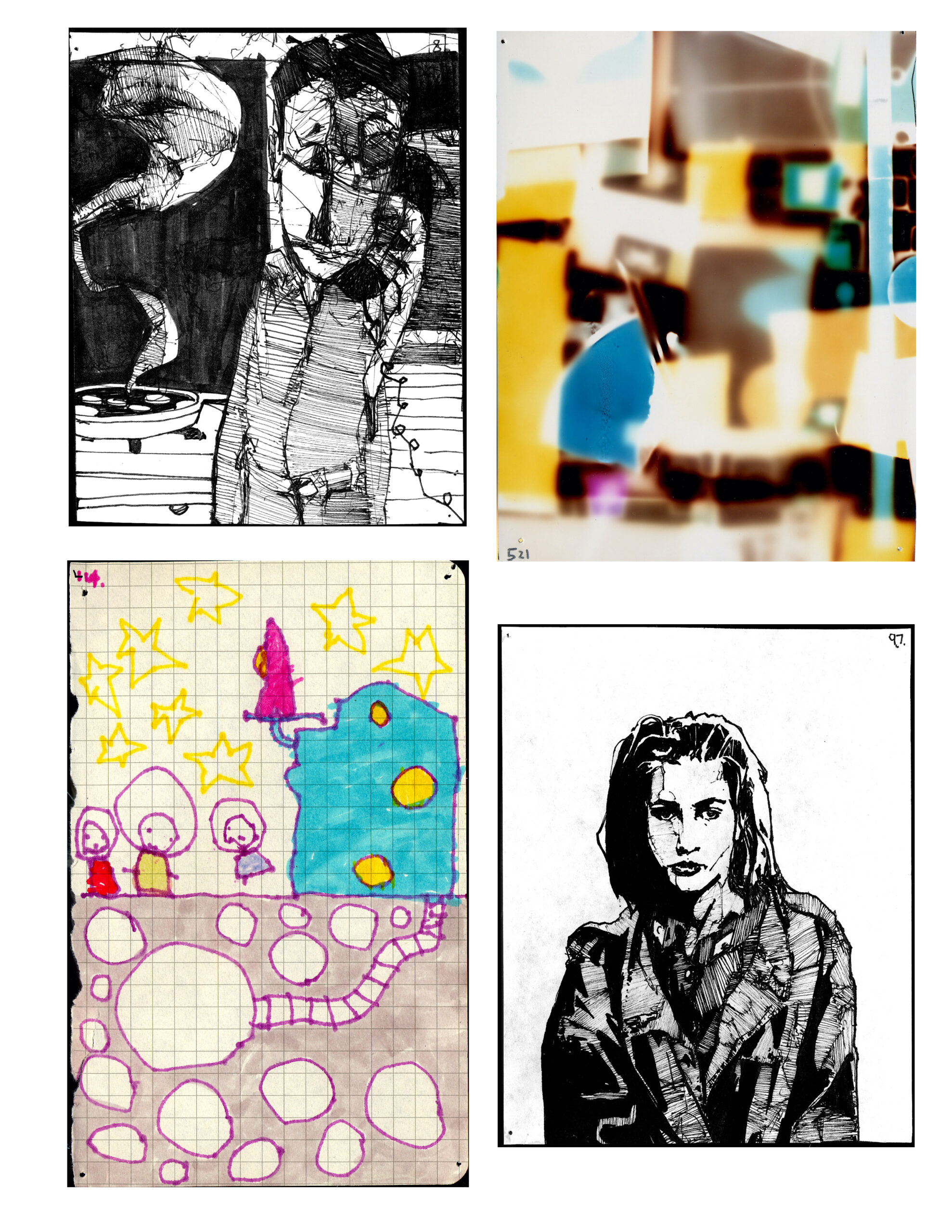

Zak Smith, Pictures Showing What Happens on Each Page of Thomas Pynchon’s Novel Gravity’s Rainbow (2004). Courtesy of Walker Art Center and the artist.

After growing up in Maryland and Washington D.C., Smith’s signature combination of the frenetic and the meticulous was first shown to the public in group shows at New York’s legendary DIY punk venue ABCNoRio. Propelled by grants, scholarships and loans, his career quickly escalated. His first portrait commission was by soon-to-be Deitch Projects painter Kristin Baker while they were still in school together at Yale—Smith himself was snapped up by the art world proper within the year.

“Zak was included by Kiki Smith and Sam Messer in a show they curated for us, “says Smith’s longtime gallerist Jessica Fredericks. “He came into the gallery one afternoon dressed like a gutterpunk, carrying a rolled-up painting, and left it on the counter. We didn’t even look at it until after he was gone, but when we finally unrolled it we were stunned. A week later we went to his studio. The work had this labyrinthine complexity that echoed German Expressionism but was entirely his own: paint that dripped, pooled, scraped, and moved through different languages all at once. We fell in love with it on the spot.”

So did many others, especially those on the art-world’s more ragged edges. Joyce Carol Oates called Smith’s 2015 two-man show with postmodern writer William Vollmann “striking, bizarrely wonderful, genuinely eccentric, weird & resonant.” Celebrated British experimental sci-fi author China Miéville asked to work on a children’s book with him (The Worst Breakfast—2016). Artist-cartoonist-journalist Molly Crabapple said simply “All the lines look like they’re on speed,” and fellow painter Inka Essenhigh once said to him, “You really like the women that you paint but I don’t get that you erase any pain.”

“I think in a way maybe everyone thinks they’re an outsider,” said Caledonia Curry (also known as multimedia artist Swoon, whose guerrilla punk-junk raft-intervention Swimming Cities of Serenissima grabbed critical attention at the 2009 Venice Biennale). “I think some people are more outsiders than others, making their own paths, and I think Zak really has that.”

Zak Smith, Girls In the Naked Girl Business: Charlie, 2004. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art and the artist.

Smith’s studio is an at-first-overwhelming avalanche of curated and surprisingly organized visual information five rows deep. It is legitimately like walking into a Zak Smith’ painting—thick with colored cubes, images of people and things, and undecipherable bits of writing strewn about that beckon you to come in and take a closer look.

“He tries to incorporate chaos as a kind of prop,” Emma Webster reported once, discussing the process of sitting for Smith. “He gets into the weeds, into the dust-bunnies on a level that most people try to avoid.” The studio bears that out. I’d be lying if I said it didn’t read a bit of manic-artist-hoarder, but instead of stacked newspapers and trash bags, it’s stacked with sketches, painting supplies, books, games, toys, and a healthy collection of thrifted salesmen’s suitcases and battered makeup cases, all surrounding a steel surgical table covered with a new painting of naked women spilling out of gridded niches hedged by piles of acrylic paint bottles and a dozen or so mason jars filled with tiny 5/0 and 20/0-sized brushes.

I ask to use the bathroom but between there and the studio is a kitchen whose floor is completely covered with all of the drawings and paintings that Smith is looking at for the next show. I try to judge whether there’s enough space for me to put a foot so that I can make my way across the minefield but there isn’t. So, Smith, in shorts, socks, and requisite black-t-shirt-advertising-obscure-hardcore-band, moves some art and I make my way through.

I come back from the bathroom and start writing some notes, then Smith interrupts asking for my help pinning work to his wall. He’s considering what to include for an exhibition titled “Phallus :: Fascinum :: Fascism,” a large group show at Mara McCarthy’s gallery The Box featuring many of LA’s most prominent artists. Primary curator Robert Stark’s unusually long press release starts with the interlinked etymology of the words involved before moving on to its historical thesis about ancient Rome’s influence on our current sexual mores: “What began as pragmatic concerns about maintaining adequate military recruitment gradually evolved into a comprehensive system of legal and social controls that systematically suppressed non-procreative sexual behaviors.”

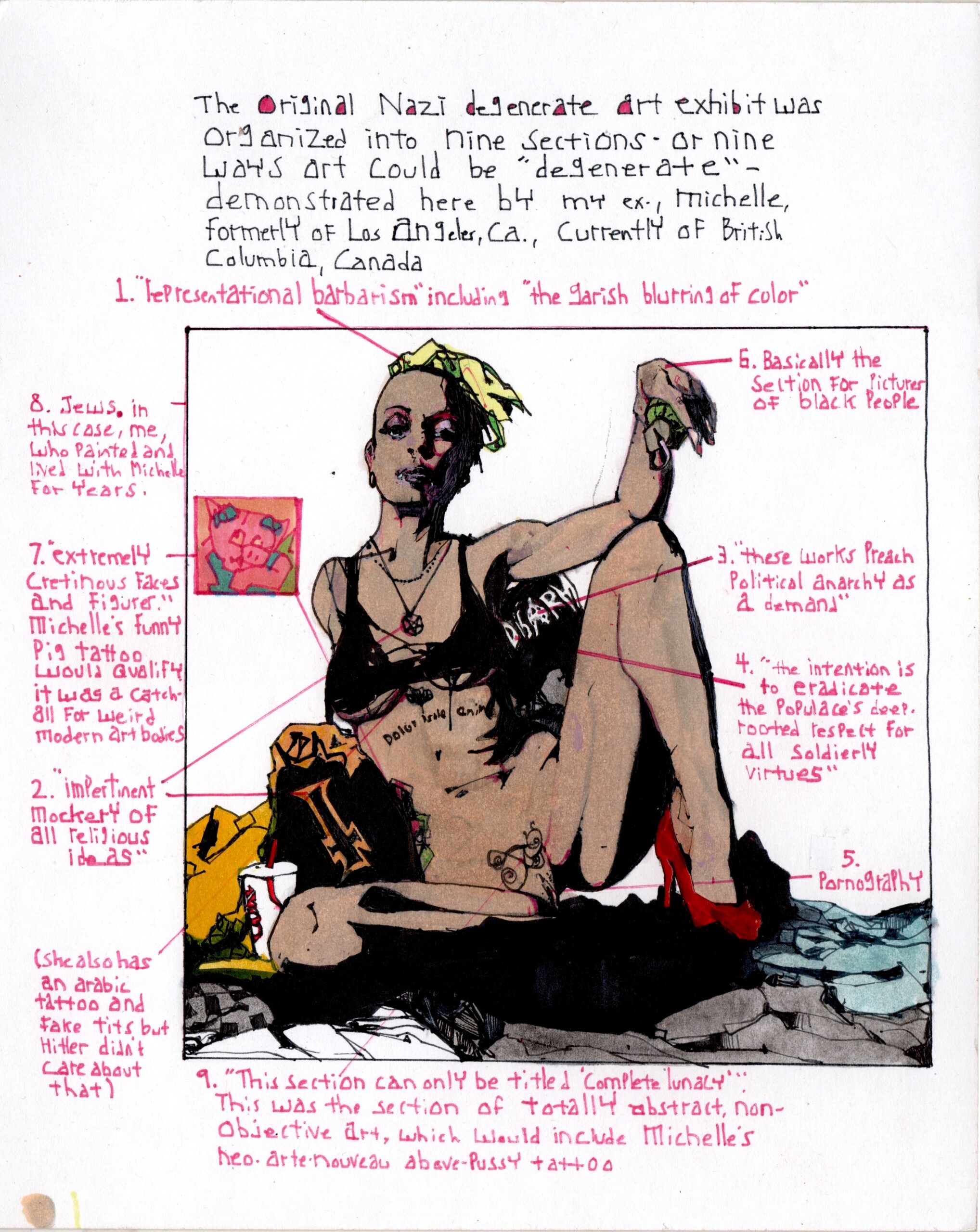

Zak Smith, Degenerate Art Notebook (detail) (2025). Courtesy of the artist.

Smith’s contribution, dozens of pages from his ever-growing Degenerate Art Notebook—a collection of drawings, paintings, diagrams, abstractions and notes—seems unusually at home in the anarchic installation, functioning as a debauchedly cishet punk-left gloss on the show’s thesis and all of the art in it. The core thread of the Notebook is an investigation of the myriad connections between the Nazi’s idea of Degenerate Art and modern conceptions of criticism, and moral panic. “The point in a modern capitalist regime,” says Smith “is not to be caught openly censoring sexuality, but to subtly put it in a place where it’s undiscussable—at least in any serious way. They want to deactivate the biggest motivating factor in the entire world as part of the discussion about power and who has it.”

My eyes settle on the multiple variations of a woman on all fours with two fingers probing her vagina, painted from the rear view—but my mind does not read them as pornographic and I ask myself why. I realize, Smith isn’t painting these images so that the viewer becomes aroused. These are not pornographic in that sense, and there is a sadness in the paintings. The women aren’t smiling and too many pieces of the paintings are left undone or are left undecipherable unless you step closer, figuratively and often literally. A Zak Smith painting seen from ten feet away is a Zak Smith barely seen.

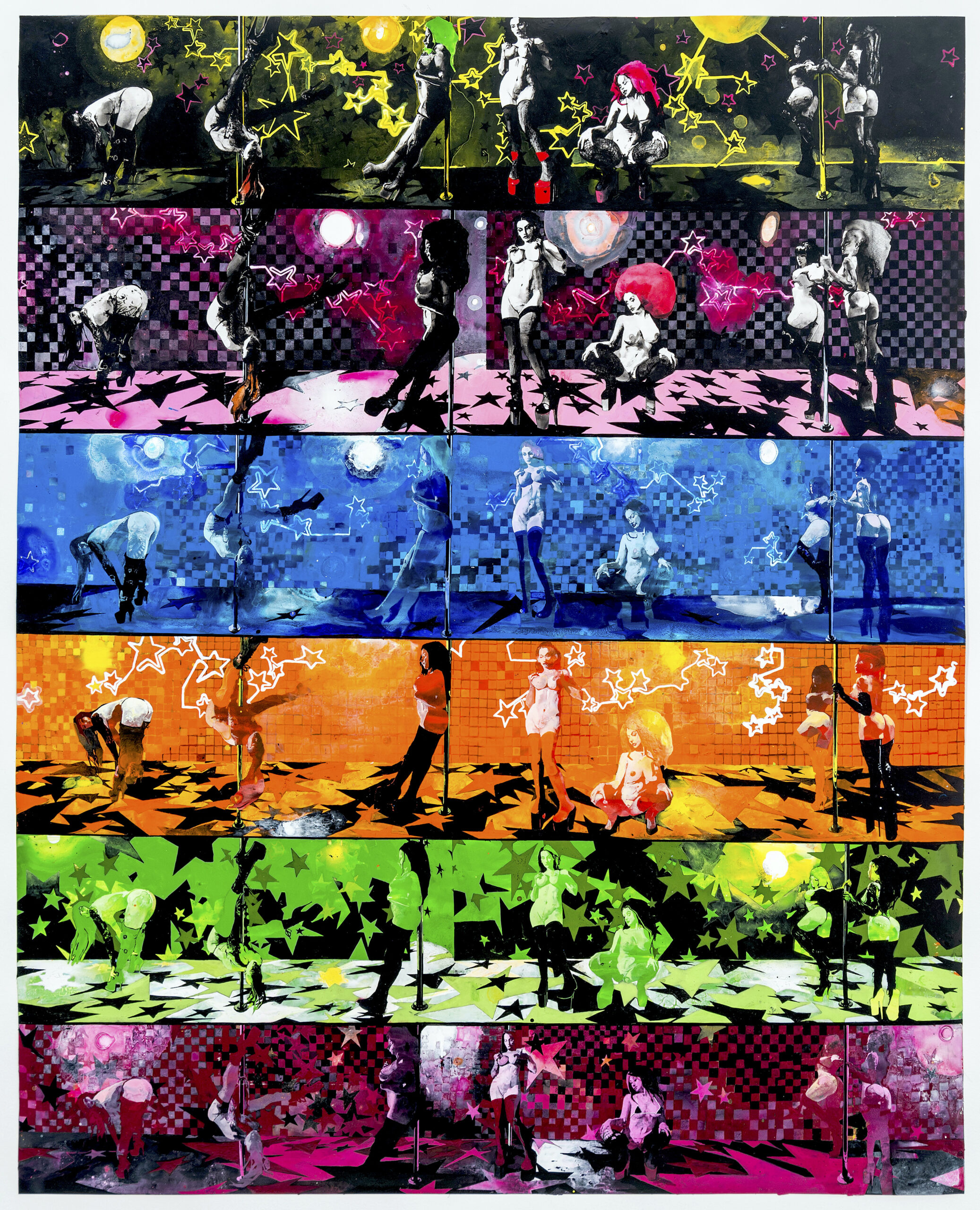

Zak Smith, Star Garden (2021). Courtesy Fredericks Freiser Gallery and the artist.

Smith’s life has been as messy as the demimondaine bedrooms he depicts. In 2019, his estranged wife, porn actress Amanda Nagy aka Mandy Morbid (who, according to court documents admitted to physically assaulting Smith and who has been clinically diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder despite denying it) mobilized friends and her following among gamers into an online campaign against Smith, claiming he was a felon of literally record-breaking proportions.

Smith was never charged with any crime but responded to the resulting online harassment by successfully suing those who made and repeated Nagy and company’s allegations five times in five countries. As of a decision in October 2025, Smith has successfully prevailed in these defamation suits in the US, New Zealand, Canada, Australia and Switzerland (“while having a pentagram tattooed on my jaw,” Smith adds mordantly) including a verdict in August against Morbid herself.

In addition, a series of interviews conducted by Oxford-spawned therapist and researcher Dr. Clio Weisman took a deep dive into the allegations and the scene that disseminated them and found many members of Morbid’s network admitting they did not take steps to verify the allegations and, in fact, fabricated other claims about Smith’s alleged crimes. Weisman likewise found that none of the harassers could provide any links or screenshots to the incriminating or harmful things they claimed Smith posted online.

Although Weisman attempted to de-circulate her article and the attached interview clips soon after publishing (once the gamers she interviewed began to focus their attention on her), Artillery’s reporting (including access to the full sixty-hours of audio interviews) confirms all of her factual claims about Smith and his accusers. Despite this, attacks against Smith continue, especially on sites dedicated to gaming.

“I want to state clearly,” said one former member of a large harassment group associated with the website Something Awful, “We made it up—that’s what you did in the 20teens: if you didn’t like someone you went online and called them a misogynist and a transmisogynist and you didn’t look back. And, yeah, I feel stupid but I won’t publicly apologize because if I did I’d lose all my friends in the scene—our entire business was built on being extremely online about social justice. And I’m dead-ass sure I’m not the only one.”

While open attacks have slowed ever since Smith’s third successful lawsuit in 2023, many have continued to spread the allegations online, most aggressively Simon McNeil (aka Simonm223) author of a fantasy novel set in post-apocalyptic Toronto and a porn photographer named Vinh (aka Morbidthoughts and Morbidiafd) curator of the Internet Adult Film Database—a site dedicated to cataloging the minute details of porn performers’ lives—who has been directly asked to stop by multiple women he’s photographed.

When contacted about their reasons for continuing their campaigns against Smith, both men declined to comment.

To Smith, it’s all part of the same complex: “It’s a short leap from ‘I think this artwork is harmful I will not be taking questions at this time’ to ‘I think this artist is harmful I will not be taking questions at this time’.”

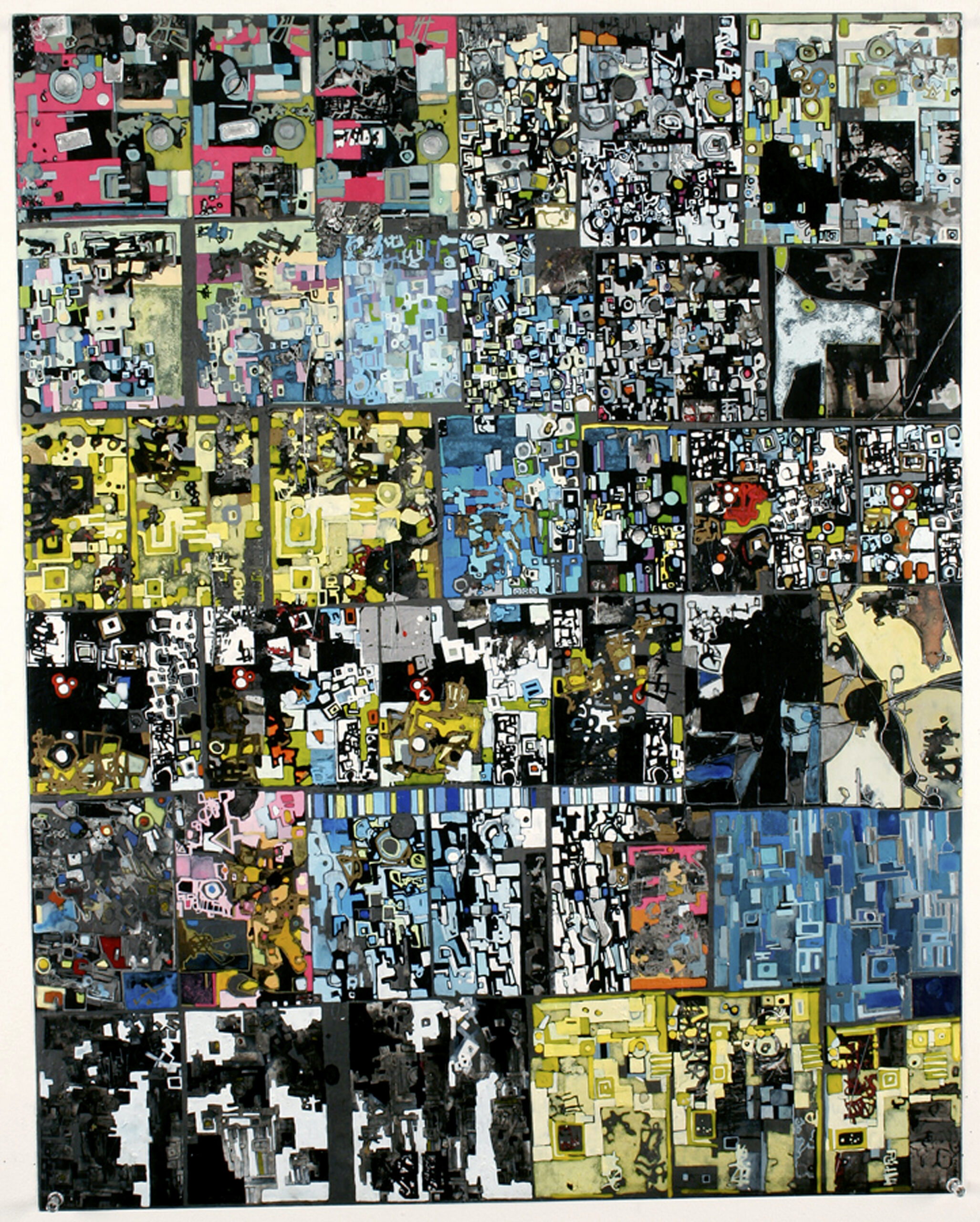

Zak Smith, Welcome Back to Fucked, (2005). Courtesy of Fredericks Freiser Gallery and the artist.

Smith is no stranger to controversy and culture war, as is well-documented in We Did Porn—his illustrated book about his mid-career sideline working as an actor in adult film under the name Zak Sabbath. The memoir (Kirkus Review: ”intelligent, frank, and often hilarious.” Penthouse: “exhaustive, perceptive, empathic, and very funny.”) highlights what is perhaps the most surprising thing in the surprisingly complicated life and career of Zak Smith—his obsessive directness. We expect our visual artists to use words obliquely when they use them at all, and to maintain a poetic mystique about those words’ relationship to the work. Smith is having none of it—in any medium. In We Did Porn, he mentions the fact that the porn industry is larger than the auto industry, and lays out a thought experiment to make the idea concrete:

“So how much porn is there? To make the real-but-invisible visible, we have to imagine that, instead of a yellow Chevy Impala parked across the narrow side street covered in graying fall leaves, there’s a little blonde cheerleader in soaking moist white cotton panties parked across the narrow side street covered in graying fall leaves and instead of crawling each morning into a bone-white Corolla, you crawl each morning into barely legal brats just dying to suck you off; that there are desperate, wet MILFs upon MILFs where once there were fleets of cop cars and cabs; that the freeway traffic jam that interrupts any attempt to feel a day in Los Angeles is vivid and continuous and urban is not a drab steel sea with passengers under glass but sixteen lanes of hand jobs, tit fucks, cream-guzzling teens, and oiled-up bubble butts glistening under a rush hour sun and going off in both directions, quivering past all the exits and dust-caked, arrowed names of subcities and streets; that, indeed, all the rest of the city and planet is constantly crisscrossed by fantastic snatch moving at every speed, so much that we can barely breathe without inhaling a wet, pale tide of nocturnal emissions so vast it threatens to eat away the shell of stratospheric molecules that keeps us from being fried alive by our world’s own nourishing sun. Then we can grasp the extent of what people refuse to discuss.”

Zak Smith, Riae Shooting In London (2021). Courtesy of Fredericks and Freiser Gallery and the artist.

Next to We Did Porn and his ongoing series of Girls in the Naked Girl Business portraits—which has now lasted from the last days of studio DVD porn, through the industry-wide chaos wrought by PornHub and into the every-girl-has OnlyFans era—the Degenerate Art Notebook emerges as one more angle from which Smith interrogates the public conversation about sex and the women who are its symbols.

The Notebook lays out, with TED-talk clarity, the links between would-be-progressives like Max Nordau (the Jewish socialist and Zionist who popularized the idea of “degenerate art” before Hitler appropriated it), music-censoring second lady Tipper Gore, anti-porn activists and puritanical critics with their explicitly socially-conservative counterparts and the results on art and artists of all kinds. In perhaps the most interesting text page he muses on a wholly fictional painting by the gay Russian spy Bill Haydon from John le Carré’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy and its various adaptations—juxtaposing the author’s different descriptions of Haydon’s oeuvre, personality and painting with musings on the complexities of pinning political meaning to images.

Perhaps the mania for explanation lies in the fact that Smith likes to do things himself, up to and including the explication (even his most ambitious paintings are done freehand, without projection, tracing or any help from assistants). What does he think of artists with factories? “I don’t understand why you’d make all these sacrifices to have a fun job and then don’t do the fun part. Go do something where you get dental.” But even Velasquez used assistants? “Yeah, and if you look at those portraits the further you get from the person’s head the more fucked up the lace looks.”

Asked why he thinks newscasters, punks, porn actresses, novelists, and fellow painters all seem to appreciate what he’s up to, he cites this work ethic: “Everything has already been done—but most of it has been done half-assed. It leaves a gap in the market for those of us who give a shit.”