Orientalist painting fantasies satirically intertwine with characters of anti-colonial resistance in “Les Femmes d’Alger,” Asad Faulwell’s ongoing portrait series recently exhibited at DENK. Drawing upon the rich legacies of Algerian War history, Islamic aesthetics and European harem paintings, Faulwell’s collage/painting hybrids critique the fatuousness of black-and-white moralism pervading messy situations where conflicting notions are so tightly entangled that no one can cleanly dissever truth from propaganda.

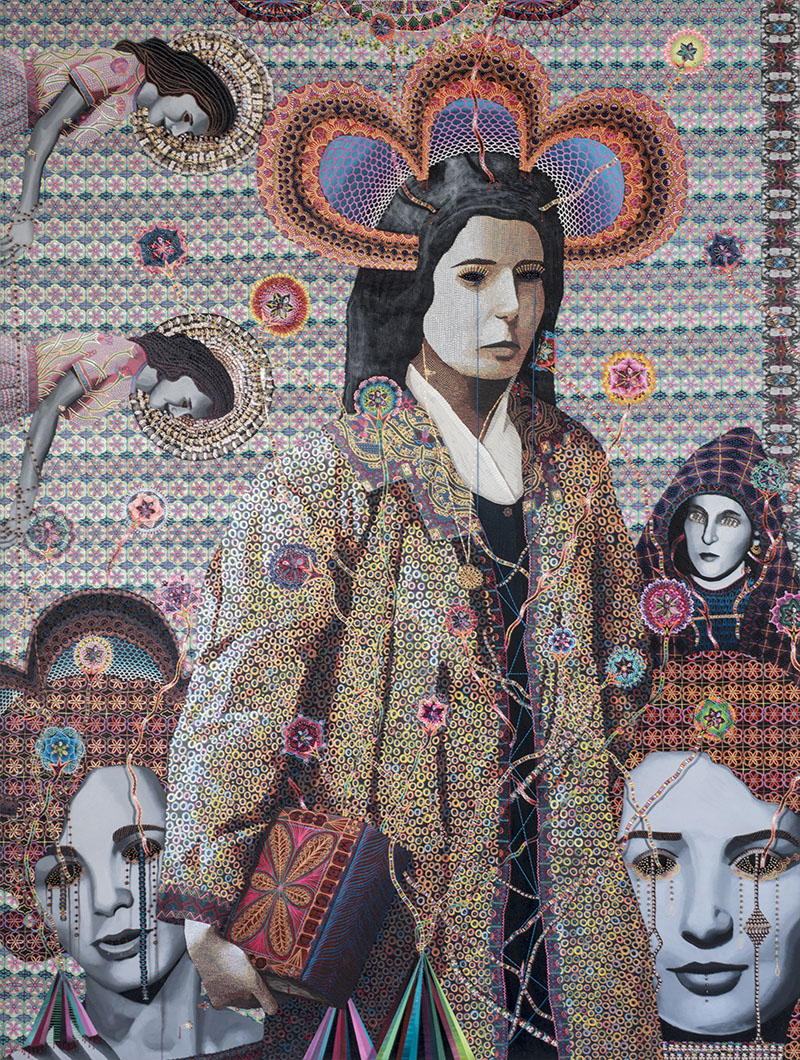

Faulwell titled his series after two Delacroix paintings called “Femmes d’Alger” (1834, 1849) and Picasso’s eponymous 1954–55 Delacroix homage. In mordant contrast to their Orientalist oil paintings of scantily clad fictive Algerian women seductively posed to gratify Europeans, Faulwell’s ornately Islamic “Femmes d’Alger” portrays female National Liberation Front (FLN) combatants who conducted violent missions such as bombing cafes crowded with French civilians. Terrorists to the French, heroines to the FLN, they were instrumental in precipitating Algerian independence.

Faulwell’s series was inspired by the 1966 movie “The Battle of Algiers,” which presents a complex picture of the FLN’s guerrilla warfare and French counter-insurgency in urban Algiers. Events portrayed in the film indicate that while each side of the conflict had valid motivations, each resorted to barbarous tactics.

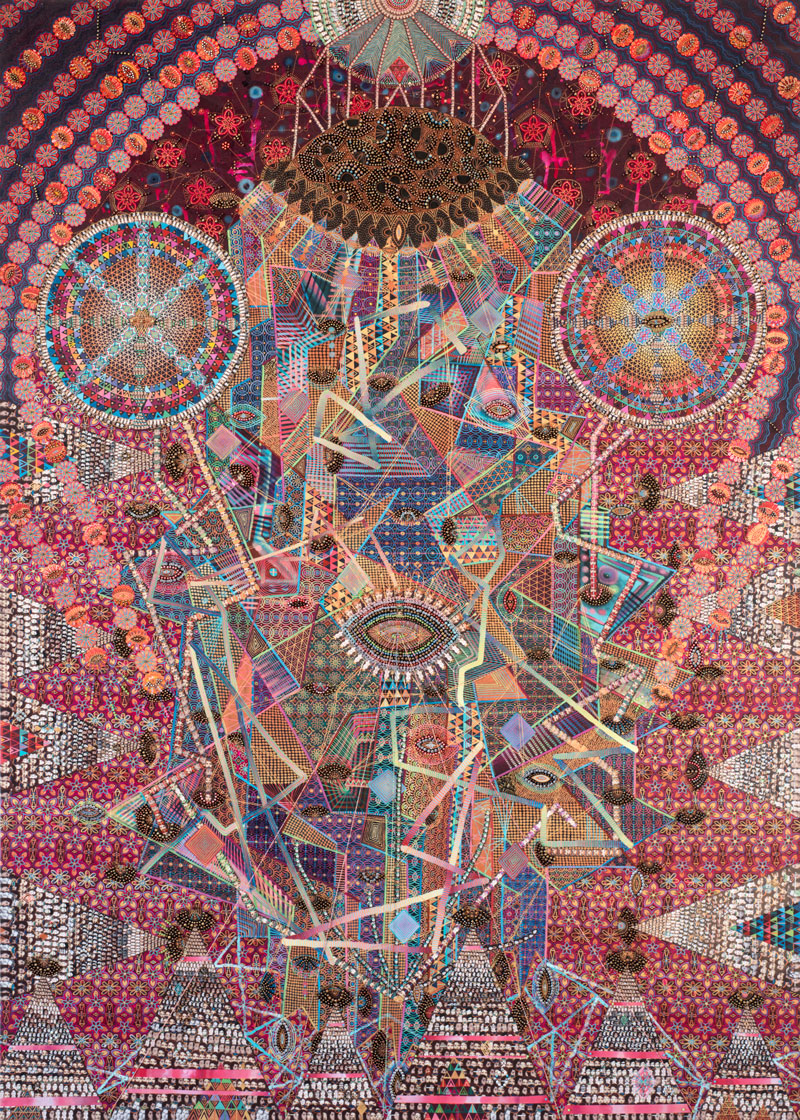

Likewise, the embellished comeliness of Faulwell’s portraits bely disquieting details symbolizing the complicated personas behind the bombers’ superficial glamour. Surrounding their grisaille semblances, colorful flowers, haloes, ornamental filigrees and collaged photos signify dignity and consequence without disclosing much individuality. These women might be beautiful were their eyes not blackened, obliterated, and interlaced with serpentine vines. Their mask-like countenances bring to mind sphinxes embedded with riddles pertaining to motivations and morals.

Multitudes of tiny photographs of female FLN combatants collaged onto Faulwell’s monumental individual portraits could represent myriad sub-personalities within each woman, or within the movement that drove them to violence. The sheer complexity of his mosaic-like paintings evokes the dizzying intricacy of warfare’s tangled loyalties and unmoored ethics. Aggrandized faces are dotted with beads of paint sinisterly resembling reptilian scales. Fancy black-and-gold-headed pins decoratively puncture their heads. Miniscule painted blood droplets betoken the brutal deeds of these women, as well as the violence enacted upon them by the French and even by their own FLN comrades.

After their dauntless exploits had helped win the war, female combatants were essentially discarded by the very movement for which they had fought. For some, having battled French rule was only the beginning of a new fight for equality in independent Algeria whose nascent government even denied women some of the rights they had been afforded under oppressive French rule.

“Phantom,” the title of Faulwell’s show, encompasses the historic erasure of these largely forgotten warriors. The artist has stated that names and information can be found for only about a score of the thousands of women who fought in the Algerian War; and even that documentation is scarce. The protagonists of his paintings appear as statues shimmering outwardly but hollow inside; the substance of their personalities and motives has mostly been occluded. Yet the fact remains that unlike Delacroix and Picasso’s Parisian models, Faulwell’s spectral subjects were real women of Algiers.