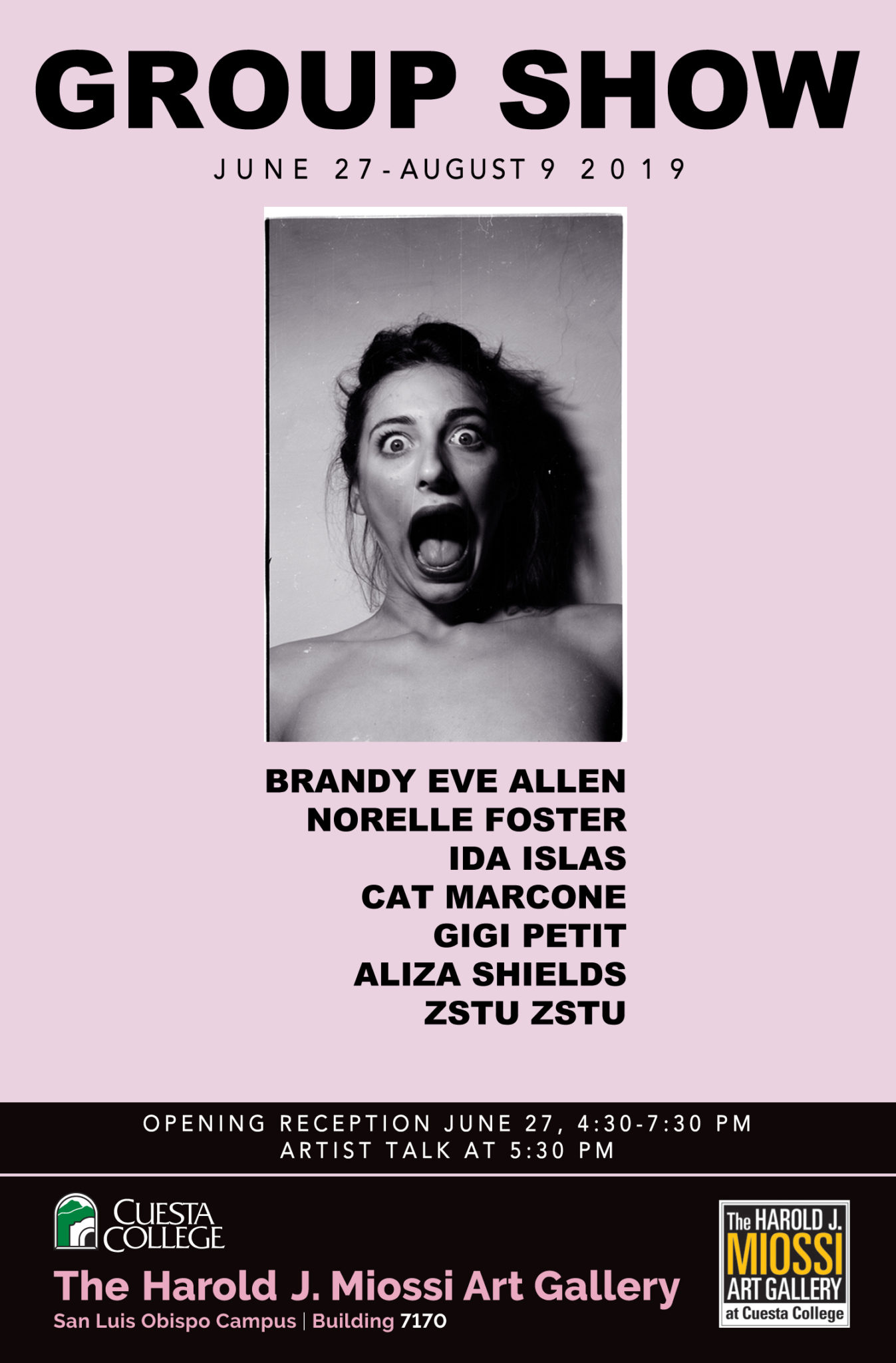

GROUP SHOW, meta-titled, runs from June 27 to August 9 at the Harold J. Miossi gallery at Cuesta College in San Luis Obispo, and features seven women photographic artists: Brandy Eve Allen, Norelle Foster, Ida Islas, Cat Marcone, Gigi Petit, Aliza Shields, and Zstu Zstu. The show’s opening reception will be held from 4:30 p.m. to 7:30 p.m. on June 27.

Allen, the Los Angeles-based photographer who also curated the show, has selected a range of work with a subtle interplay of subjectivities: the artists’ works seem to speak to one another while maintaining specificity, the ideal scenario for a group presentation. If you’re going to road trip for one show this summer, let it be this one.

Performance artist Ida Islas considers herself “an agent of intimacy and love.” You can call her to schedule a coffee date at 1-800-633-1403, or find her roses scattered around Los Angeles as an offering to those who lead with their hearts.

Aliza Shields, concerned with displacement and lineage, seeks inspiration from the California landscape from which she hails. She creates photographic works in remote areas of the central coast and in Los Angeles, juxtaposing artificial materials with natural landscapes. She holds an MFA from Yale.

Cat Marcone documents affectionate and visceral experiences within youth culture. Her photographs and writing offer a window into the pressures of becoming an adult while illustrating the unrequited love, discovery and the personal transformation one goes through as they come of age. Dante’s definition of hell is “proximity without intimacy.” In this hell, a room is full of people but no one is truly connecting or seeing each other. Marcone’s work aims to go beneath the surface, where images are less about what things look like and more about what they feel like.

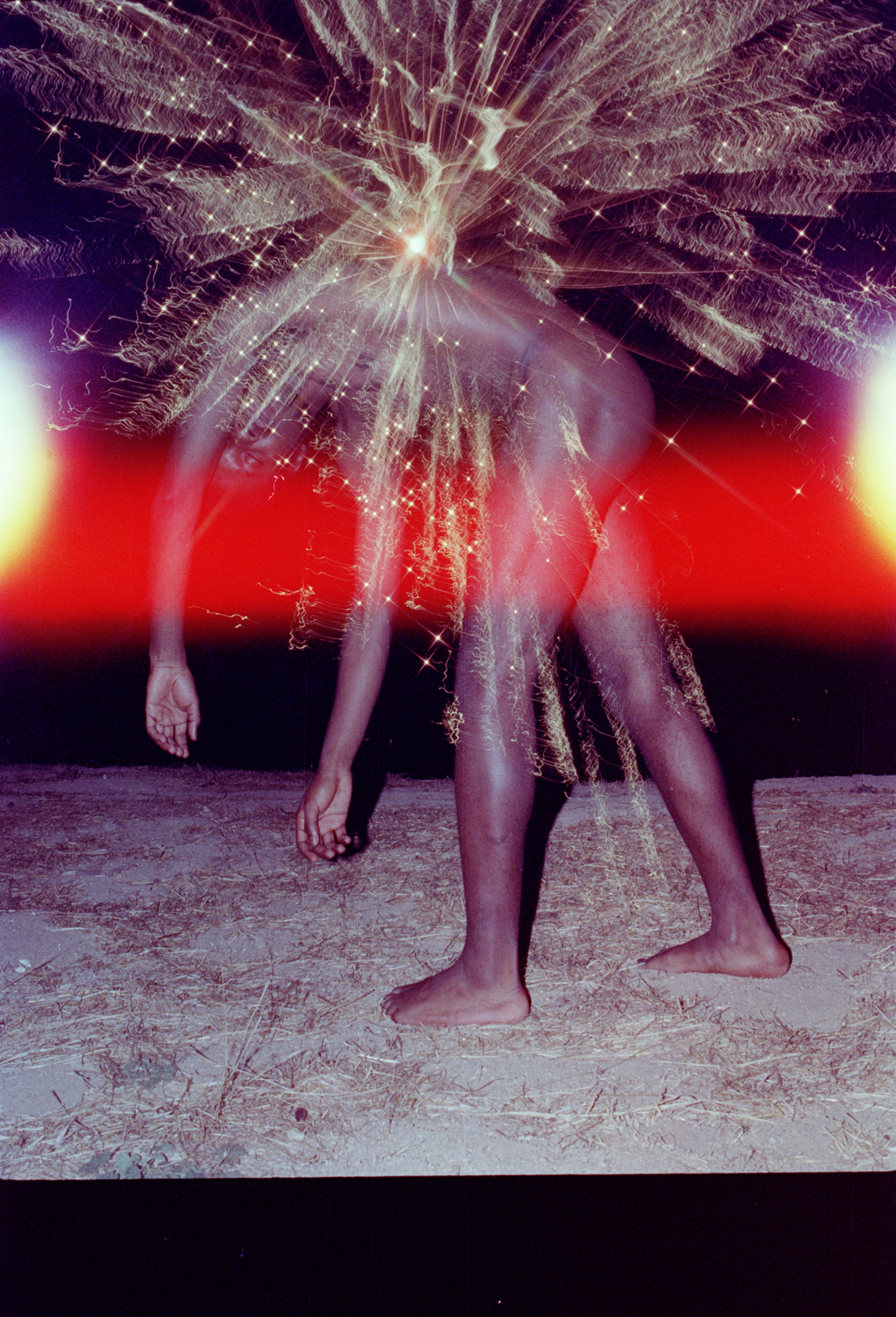

Zstu Zstu creates photographs that speak for the rejected, electric and divine facets of ourselves. Layering imagery through multiple exposure techniques, her images are a combination of intention and accident. Zstu Zstu melds time and space, conjuring feelings of nostalgia and the supernatural. She is using iconographic motifs as a way of tapping into the mythological intergalactic realms of the human soul.

Brandy Eve Allen’s self-portraits explore the artist’s identity, emotional and mental states, and the expectations of female experience. Self-documenting is a method for solidifying one’s existence and has always been a way to control one’s own representation. There is a refusal to be still in Allen’s work, a representation for the ever-changing identity and evolution of self.

Norelle Foster b. 1984 – d. 2012 was a self-taught photographer who focused on the South and Central coast of California. Her work takes on a mythological ethos, referencing symbolism and archetypes that echo the likes of Lilith, Saint Theresa, Cleopatra and Joan of Arc. Her work invokes the antithesis of violence without dismissing its counterpart.

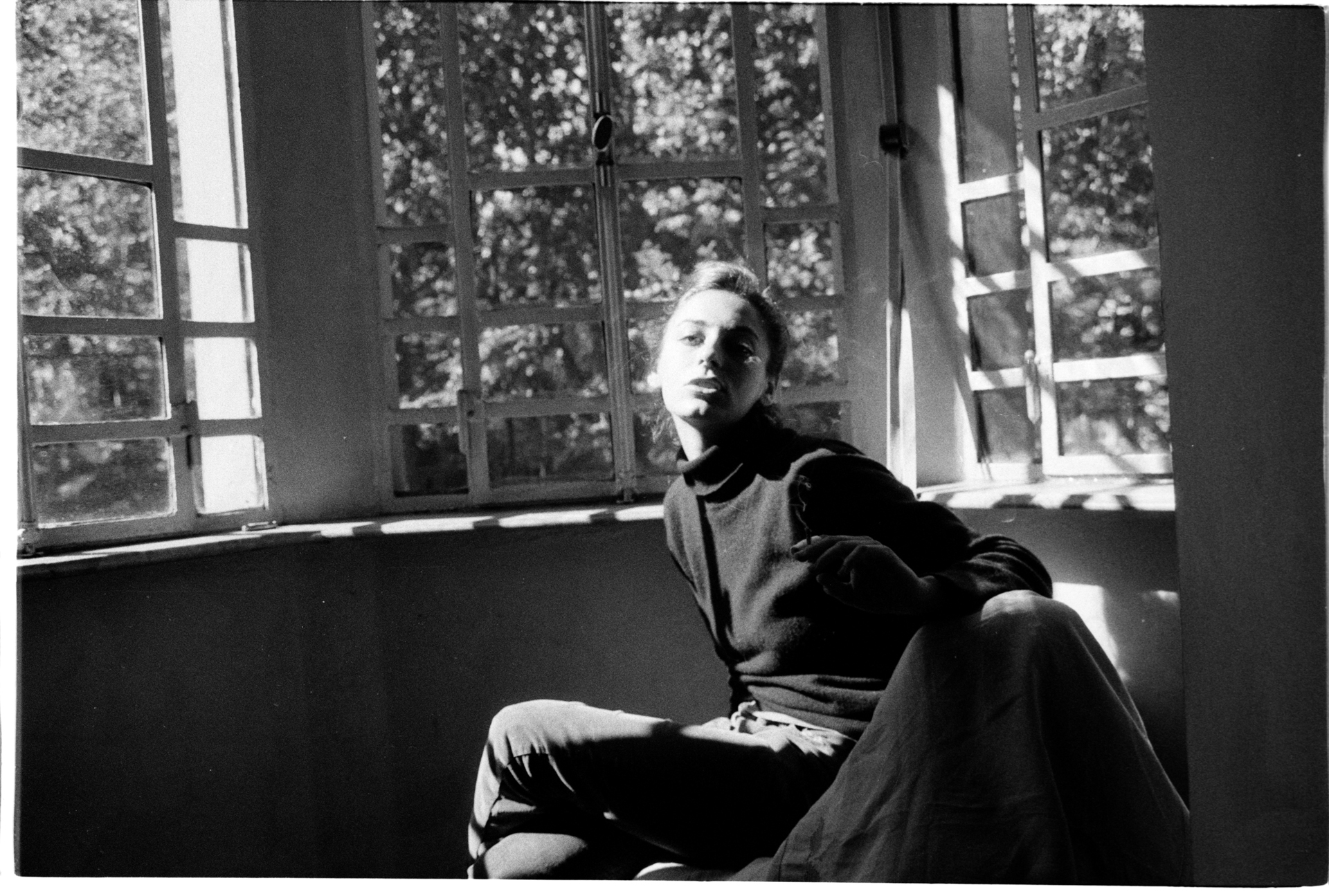

Gigi Petit captures her subjects with a raw and tender nature, exposing wounds perhaps ready to be licked, sometimes not. Her photos are not about the circumstances, but rather the people sitting quietly in the frame.

I chatted with Brandy about her vision for the show, and briefly with each of the living artists about their practice.

Tell us about the pieces you chose to feature in the show. Do you think of them as speaking to the other work?

These are not conceptually based artists, although they are concepts. The common thread between the images being shown is that they are all very personal.

How is engaging with the work of other artists part of your process?

The process is pretty isolated, but as an artist, it’s important to support other artists, so that’s part of my process.

You’re largely self-taught. How did you come to your medium? Do you ever teach other artists?

There are artists in the show who have learned independently and one that has gone through the system, one speaks specifically about how being admitted into these spaces doesn’t guarantee complete access. One of the artists is a mentor to several younger artists, opening up her home, feeding them, lending out equipment, and having meaningful conversations about life and creativity. Even though this is a photography show, a lot of these artists come from backgrounds in painting, dancing, writing, music, and performance. To quote Marvin Gaye: “We’re are all sensitive people.”

Art — or at least, the art world — is largely a symbol of systemic inequity: the absence of woman artists in museums, art history, school curriculum, etc, mirrors the everyday experience of women. Is this something you consciously engage with?

I would say it’s something that engages with me. I have to consciously disengage because I can’t get caught up in the bullshit, and a lot of it is bullshit. I think as we bring in a greater awareness of underrepresented artists, they’re also being exploited by the same people opening doors. In the end, there’s so much hidden emphasis on profit masquerading as social change. But every0ne has always been exploiting everyone. I think it’s important for us to learn from the past but moving forward to not allow for these giant flaws in the system to define or deter us from our goals. Sometimes so much emphasis on the struggle can get overwhelming and once finds themselves feeling discouraged.

Do you think of the gendered images in the show as using the female as a path to the universal?

The ratio of female subjects is greater than men, however, I feel that each gender is engaging the other and transcending those terms. I would say that the female is used as a path to the universal like you said, where it goes deeper into a human experience void of sex classifications.

One of the striking things about this show is that each artist’s work seems to be in and of the world, unencumbered by the eventuality of ending up in a gallery (which is refreshing). Do you think about the audience at any point while creating these images?

Some of these artists have been making art for more than twenty years, all of them are creating art according to what they want to do — not what anyone is telling them to do. Some of them have a full, overwhelming range of work with a sophisticated process that sometimes gets overlooked in today’s digital age. The art world is so on-trend and if something doesn’t line up at the right time, it doesn’t happen — some of the artists have suffered from this. Some of them have suffered from leaving a bad taste in people’s mouth whether they had a bad attitude or a lack of pedigree. Sometimes, we as artists aren’t ready and need to develop our style and voice even further, even when we feel like the last thing we did was fucking groundbreaking. What’s great about all this is we continue to make art and our struggles as artists have begun to inform and shift some of the art itself and our approach to the process.

If all financial limits were lifted, do you imagine anything in your practice changing?

Most definitely, yes. Many of us are limited by financial restraints but make the most out of what is available. Money is the freedom to play beyond your means, so unlocking the possibility to work with different materials and larger scale productions and pieces would be exciting.

It seems like there is either a tradition of self-portraits by artists as somehow divorced from the rest of their work, or that they primarily manipulate their own image (ie Cindy Sherman). How do you handle the switch from being the observer to being the observed? How does one observe oneself?

You can observe yourself in all kinds of ways. Sometimes I’m real, sometimes I’m contrived, sometimes I’m experimenting. What am I saying within these experiments is it’s okay to explore and figure out nothing within the absurdities of this existence. It’s not that I’m celebrating the mundane and that nothing matters, I’m just poking and making fun of how seriously we can take ourselves sometimes. I’m going deep and I’m also okay not being deep. I’m a fucking paradox and so are you. Another reason I photograph myself is I don’t want to make art with other people and with photography that is an assumed aspect of the medium. You should just think of me as a poet with a camera and instead of writing, I’m taking pictures, but the verse is the same; it’s ambiguous within my instinctual nature, my performance, my vanity, and insecurity, my existing, my nothingness.

With your bubbles, you’re depicting something so far from the body, yet somehow, they feel corporeal.

Alien in nature, these amoebas are meant to emulate the strange nature of humanity walking through this earth. All of the materials are reactionary to the elements around them, there is movement and moments are fleeting and so is life.

Where are you living now?

I’m on sabbatical living in Cayucos on the Central Coast — giving master classes at universities between San Francisco and Los Angeles.

You are formally, academically trained as a photographer, but often speak about identifying with outsider culture. How do you experience this dichotomy?

Being a part of academic elitism… not everyone who had the privilege to be admitted into the system was accepted by the system. Most of my work allowed me to remove myself from the physical confines of the classroom. Being admitted into these spaces didn’t guarantee or grant complete access.

Norelle Foster:

How do you choose which body to layer with which space? How much is chance a part of this process?

As much as the photos are left to chance, they also consist of thoughtful orchestration. I am setting everything up compositionally and technically so that it will expose in certain areas but I cannot plan what is placed with what and in what exact position. Does that make sense? I’m shooting the rolls and then rewinding them and reshooting them, some exposures I will multiply on a single frame. It’s really a lot of experimenting and playing, but it always works out and I like to be blown away surprised by how so many of the compositions seem to line up perfectly. It’s a perfect mix of intention and randomness.

The nude form can feel like raw territory because it’s divorced from history, but these photos seem to experience or offer the experience, of stories from history.

The nude form and the elements incorporated into each photograph are a reminder that we are of this universe, we are the sea, we are the stars, we are the earth and we are here to suffer and learn and to excite ourselves and feel the ecstasy of this life. Nature is both volatile and full of beauty, like humans.

Why are you so drawn to fireworks? Is there any other meaning other than the obvious visual spectacle, the sparkle?

A firework is a beautiful explosion which is what I think this life is.

How do you engage with each person you photograph?

I’m not photographing human subjects — they become another object within the context of each image. Their bodies are speaking through a gestural language. I think words are overrated. I listen more to the way the body moves and to tone.

Many assume these double exposure images are digitally produced. How do you respond?

I’m annoyed when people assume these double exposures are digitally produced. People don’t get the full extent of the process and their moving so quickly they’re just living on assumption. And their assumption is wrong. Some of my frames consist of 7 exposures. I photograph and layer these elements at different times, rewinding the rolls and reloading them later, the process is very much a part of the piece. I could digitally overlay shit later and make it perfect, but I don’t like perfect and I also don’t like easy.

There aren’t any people in the “lovers” photos, but a sense of their absence. How do you conceive of the lovers?

“Lover” is a metaphor for living outside of yourself, for caring beyond the immediate. A lover is someone who may desire love, who is lonely for love, who sees love, who loves love. Love is a gift. Anyone can be a lover. “For the Lovers” is an offering. It stems from unrequited love. I had all this love inside and nowhere to put it. So much of art is selling something, it can become a very selfish and unsatisfying experience. The exchange is important to me and any exchange begins with an offering.

Are the roses meant to be a cliché?

I think red roses can be cliche, but in this context they are symbolic.

You invite people over for coffee as part of your performance art. What do you want people to talk about when you have coffee with them?

When I get together with people, there are no expectations. And by the way, I think expectations are good.

You’ve been very outspoken about the gallery system and how restrictive of practice and livelihood it is. Can you elaborate?

I think the ways galleries or museums and the mechanisms within these systems have been set up are full of hypocrisies and twist value into a monopoly that becomes a joke. Who is determining worth? Artists are exploited for their experiences while at the same time being shunned for same things these systems profit from. Who is the authority, what access allowed them that position? Some people look at art as a business, some people look at art as a necessity. Those who can do both are better off than I am.

Would you call yourself a performance artist?

I think we’re performing all the time or we’re alone. There’s a very special few that we can totally be ourselves. And even though the rest of the world wants to see our true selves, we can’t help but continue to perform. Performing is, therefore, a part of our humanness, we need to step into spaces that are unfamiliar and performing is a coping mechanism that allows us to go places we otherwise might not have the courage to go. I’m an artist, so yes, I would call myself a performance artist.

What are you currently working on?

These days I’m switching from cream to oat milk…

What took you away from LA? What brought you back?

Most of these images were shot in Italy and throughout Europe, they are more of a departure from Los Angeles, an escape from hell.

When you create a portrait what are you hoping to achieve?

The camera knows more than the subject here because it sees the subject within a context, something the person can’t do for herself or himself. The person can’t see themselves “in it,” they can only look out. I feel seen through each of the subjects. I’m attracted to them because we share a certain quality or understanding, so each person could be a reflection of myself.

You seem to focus on shooting young people. Do you find a kinship in these subjects?

First of all, there is the availability of these subjects. I shoot people who are available to me. Second, I am documenting a kind of privileged youth experience.

Can you talk more about this privilege?

In the way of not being self-conscious — I’ve noticed as people get older they become more insular and more private. They become more controlling about how the final image is going to be presented. The final product becomes about their vanity. That’s just my experience. I think we’re uncomfortable with seeing older people free themselves, it’s not cute until you turn 80. I’m guilty of that… judging people my age for running innocently through the desert, like that’s only the place for attractive young people who go to Coachella or something. You look silly. I think my guilt for excluding this particular age range is something I need to take a look at and challenge myself on beside the self-portraits that I create.

If I alienate my peers by presenting people who are too beautiful, too youthful, that’s a reality that I have to look at. I know people are bothered by some of the work I do and the subjects I choose. I’ll move on when I’m ready.

0 Comments