Not all films about artists and the art world are silly, but most of them are. To paraphrase a Mark Twain quote, “There are lies, damned lies, and films about artists and the art world.” (Twain linked “statistics” with lies and damned lies.) From such films as the Vincent van Gogh epic Lust for Life (1956) to the Michelangelo biopic The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965), we get overripe portrayals of the tortured soul, whose genius outshines that of ordinary humans—but the title of the latter film says it all: they’re tortured, but they’re ecstatic in their artistic being.

The tendency of Hollywood to over-romanticize is common, especially when it comes to “Great Men.” You name it, Great Men of the Arts, Great Men of Politics, Great Men of Science, etc., with an occasional—very occasional—nod to the Great Women. Even recent films seem to fall into that crevasse. I enjoyed Julian Schnabel’s Basquiat (1996) which boasts a remarkable performance by Jeffrey Wright in the title role and seems fairly evenhanded in its impressionistic portrait of the New York art world. However, recently, I read a biting critique by curator Okwui Enwezor in Frieze magazine. He pointed out that Schnabel put himself in the film as Albert Milo (Gary Oldman), and Milo, a white artist, achieves the fame plus the success and security that Basquiat, as an African American artist, did not. Enwezor also pointed out that “Milo” repainted Basquiat’s work, which is a lie.

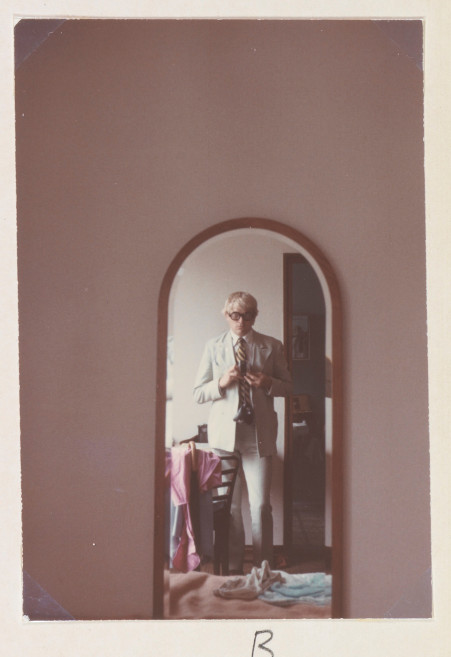

Perhaps we might be able to rely on documentaries to give us truer portraits—after all, usually the subject’s actual image and voice are used. “There’s nothing more powerful than when you have someone’s real voice telling the story,” says Lisa Immordino Vreeland, whose lively new documentary, Peggy Guggenheim: Art Addict, has just been released. Recently, we’ve also seen Hockney directed by Randall Wright, which utilizes interviews with David Hockney and those who knew him. Both Vreeland and Wright are veteran documentary filmmakers, although Wright, with his experience making BBC docs, tends to have a straightforward style, while Vreeland intersperses some jazzy special effects, graphics and editing into hers.

Wright had previously made David Hockney: Secret Knowledge (2003), which traced Hockney’s theory that artists were using optics in their work as early as the 15th- century. The first part of his new doc, Hockney, is fun, even joyous, as Hockney escapes his humble middle class background in gray, glum Bradford, England, by going to art school—the Bradford College of Art, then the Royal College of Art in London—and eventually to America. He first landed in New York, then visited California, and fell in love with Los Angeles for the light and the handsome boys. The film looks at his unending reinvention and fascination with new media—he’s worked with photo-collage using Polaroids, and he’s made videos with multiple cameras running simultaneously—although recently he has returned to watercolor and painting.

One of the strengths of the film is that it liberally mixes Hockney’s art throughout, so that we get to see the people and places that mattered to him at different times in his life. Wright also had access to Hockney’s personal video collection and to his family, so we get some intimate glimpses through clips and interviews. However, the film seems far more interested in his early life, when his career was taking off, than recent decades which are skipped through quickly.

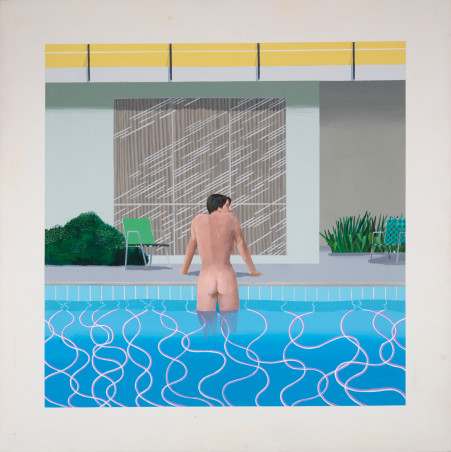

Take how the doc covers Hockney’s love affair with Peter Schlesinger, an art student he met while teaching at UCLA in 1966. Schlesinger became the subject of numerous drawings and paintings, including the famous 1966 painting, Peter Getting Out of Nick’s Pool. When the affair ended, Hockney was devastated. That break up was captured by a 1975 quasi-doc by Jack Hazan, A Bigger Splash, a film which apparently sent Hockney into depression, and which he tried to buy out. It’s curious that Hockney doesn’t cover Hockney’s romantic life of recent decades. He was in a 24-year relationship with John Fitzherbert, which ended in 2009, as reported in The Guardian in 2013. But maybe Hockney had learned his lesson from A Bigger Splash and didn’t want to mention it, especially as Fitzherbert later got involved with his studio assistant, who died in 2013 after a drug binge, topped off by drinking drain cleaner.

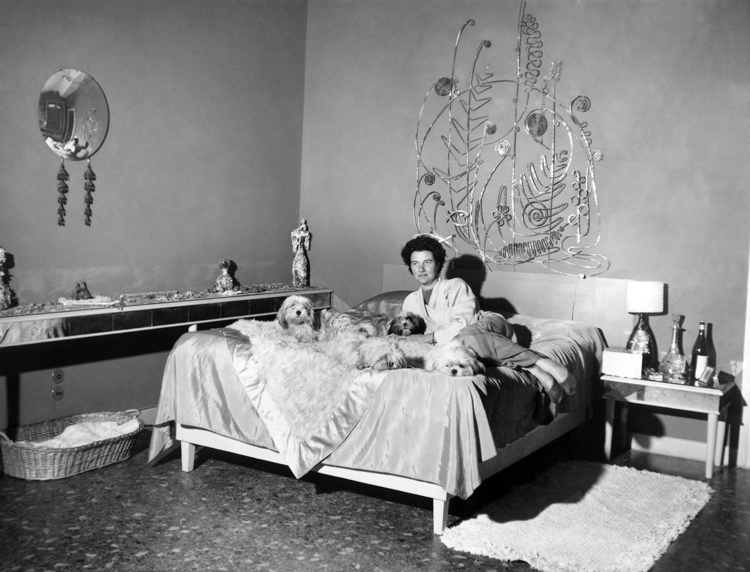

This is an affectionate, guarded portrait, while Vreeland’s Peggy Guggenheim is a warts-and-all exposé about a woman who lived large and, as art collector and art dealer, was central to defining the art of the 20th century. The core of the documentary is an audio interview, a tape recording from Guggenheim’s last interview with her biographer, Jacqueline Bograd Weld, in the late 1970s. “You’ve often thought your greatest achievement was the discovery of Pollock?” you hear Weld ask. “Yeah, I think so.” Her collection? “My second achievement.”

Raised in an upper class New York City family, Guggenheim grew up a rebel. She was naturally drawn to artists and the avant-garde, partly to spite her family, partly to establish a unique identity for herself, and partly, I think, because it was a blast. At 21, when her father died on the Titanic, Guggenheim inherited a fortune and decamped to Europe in 1920. In 1941 she returned to the U.S. and set up The Art of This Century Gallery in New York City, which was part commercial gallery and part museum. She gave first exhibitions to Hans Hofmann, Robert Motherwell and Clyfford Still. She characterizes herself succinctly, “I was the midwife.”

The film is a portrait of a woman who was ahead of her time, and she is remarkably candid and clear about her life. She went through affairs with a string of men, some of whom took advantage of her, even beat her up. Her second husband Max Ernst comes off as a stereotypical artist with an overweening male ego. Once, when she bought herself a fur coat, he got so jealous that she had to buy him one, too. After World War II ended and she divorced Ernst, she decamped to Venice, Italy, a city which matched her flamboyance and appreciated her eccentricities. Her former home is now a museum of the art she collected, the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, which is delightful and mesmerizing for the strength of its personal vision. During her lifetime, she had also given a great deal of art away—20 Jackson Pollocks by her estimation, a most generous gift.

It seems to me that we get a better sense of Peggy Guggenheim after seeing this doc than of David Hockney after seeing Hockney. Despite having such a public presence in the art world, and even courting attention through lectures, publications and films, Hockney seems essentially a private person. He is also still living, so biographers need to tred gingerly.