Often seen as an eccentric art form, ventriloquism has resurfaced and gained popularity again in mainstream culture over the past few years, from televised talent competitions (three ventriloquists have won America’s Got Talent: Terry Fator, Paul Zerdin and Darci Lynne Farmer, who was 12 years old at the time) to the hip-hop world—Kendrick Lamar appeared with a dummy on stage during his 2022 tour, and early 2000s rapper Twista is now sharing his ventriloquist skills on social media, with Rolling Stone publishing a short article on his new passion. There are even Gen-Z influencers gaining millions of views on their videos as they show off sharp technical vocal skills or create comedic bits with their puppets.

In the art world, ventriloquism has popped up through artists using dummies and institutions centering exhibitions around the art form as a theme. Perhaps the most notable artist is Laurie Simmons, who made several series of works using figures in the 1990s, such as “Clothes Make the Man” (1990–1994), composed of resin-cast sculptures of wooden dummies dressed in 1950s children clothing, and “Cafe of the Inner Mind” (1994), photographs of six male dolls arranged in different positions, sometimes with thought bubbles appearing over their heads in the

images. Simmons went on to turn the concept of her 1994 series, “The Music of Regret,” into a short film in 2006, starring Meryl Streep and the same male ventriloquist dolls that appeared in her photographs. In a 1996 interview with

Linda Yablonsky for Bomb magazine, Simmons remarked, “It’s just that the dummies and dolls have a long history. They’re not of today. But they seem more constantly human than any of the robots with computer chips can be.”

The art of ventriloquism— from the Latin words venter (stomach) and loqui (to speak)—requires not only talking while not moving one’s lips, creating the illusion that the words are coming from the dummy, but also pretending to listen while manipulating the dummy’s head and mouth at the same time. The ventriloquist has a conversation by herself, seemingly an exchange between two beings; the dummy is a medium of self-expression, yet it also defines the ventriloquist and her act.

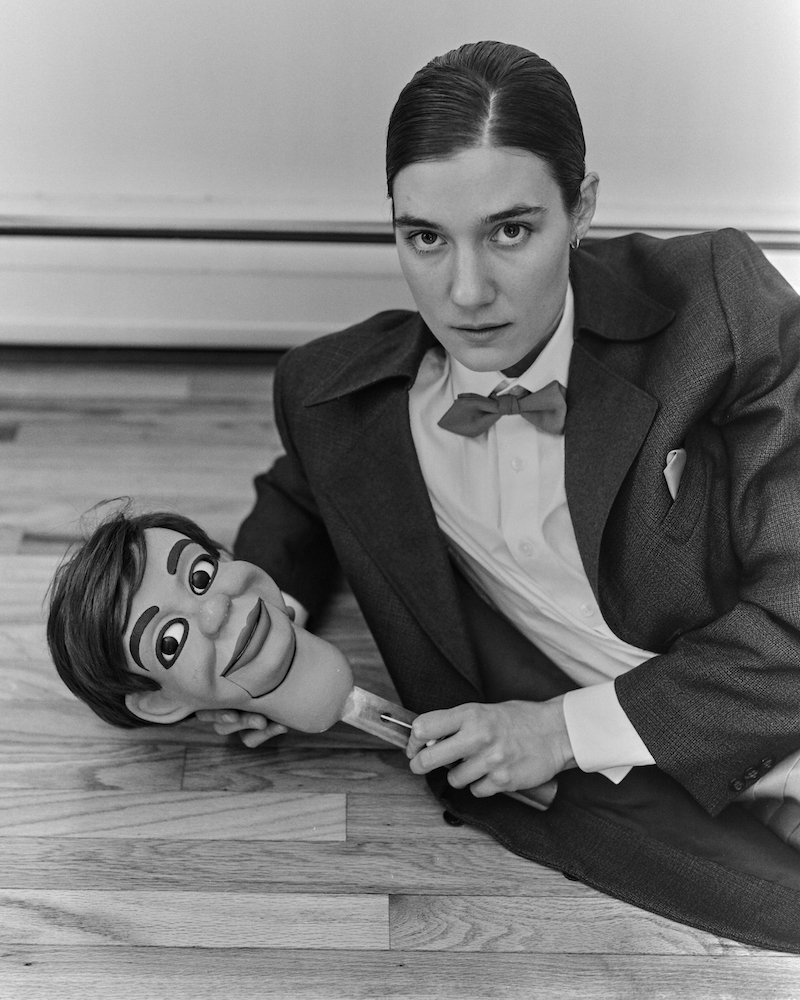

Based in New York, performer, actor and curator Sophie Becker began incorporating ventriloquism into her practice during the pandemic, her partner being a classic Jerry Mahoney figure, who was originally created by lauded ventriloquist Paul Winchell in the 1930s (and was probably a model for the male figures in Simmons’ images). Mahoney, with his friend Knucklehead Smiff, appeared on various programs such as The Ed Sullivan Show, and he even had his own, The Paul Winchell and Jerry -Mahoney Show. While touring with Bread and Puppet Theater in 2020, Becker began experimenting with ventriloquism and then honed her skills during the lockdown. In a conversation with the artist, she explained, “I thought the perfect thing to learn was ventriloquism, because I can be on stage with people whenever I want to be on stage with them and have multiple characters.” Becker and her Mahoney figure now perform around New York in matching red bow ties and suits, singing together and often lamenting about Jerry’s former fame: “Jerry hates that he used to be famous and that no one cares about him anymore. And he harps on the fact that there was, I call it, the propaganda war on ventriloquism. There were so many ventriloquists and then, all of a sudden, the bubble burst.”

Sophie Becker with Jerry Mahoney, photographed by John Spyrou.

Public perception of ventriloquism has changed substantially throughout the 20th century, mostly due to horror films (the ventriloquist’s reputation damaged almost as much as the clown’s), such as the 1978 psychological thriller Magic, in which Anthony Hopkins’ character becomes possessed and unable to control his evil dummy, Fats. The tortured ventriloquist in cinema appeared as early as 1929 in The Great Gabbo, but the idea of ventriloquism being associated with a greater evil goes back centuries: “Late antiquity to 18th-century ventriloquism was deeply embedded in Christian discourses about demon possession, necromancy and pagan idolatry,” wrote Leigh Eric Schmidt in his 1998 essay “From Demon Possession to Magic Show: Ventriloquism, Religion, and the Enlightenment.” Ventriloquism originated as a religious practice in ancient civilizations—some scholars believe that the priestess at the Oracle of Delphi and the biblical story of the Witch of Endor are two of the earliest examples. The question of whether Satan was speaking through the possessed persisted until the 1770s, when Jean-Baptiste de La Chapelle wrote “Le ventriloque, ou l’engastrimythe,” which parsed ventriloquism as an art form that consisted of a performer’s misdirection, muscular control and modulation—without supernatural elements. It then flourished as a mainstay of vaudeville, theater and entertainment, although often paired with ghost shows and exclusively male throughout the mid-19th century.

On today’s standards, Becker responded, “People think it’s super cringe, and they don’t know much about it, but no matter what, when anyone hears that I do it, they’re so excited. So there’s this weird dichotomy that I love, but I understand why people think it’s weird. The dummy is an uncanny object. Especially the Jerry Mahoney object I work with. It took a moment, psychologically, for me to adjust to having this object in my space. They are incredibly powerful objects. There’s a reason that people respond to them so intensely.”

In 2021, LACMA organized an exhibition titled “NOT I: Throwing Voices (1500 BCE–2020 CE),” which explored the art form in looser and more conceptual terms, looking at objects imbued with voices from the institution’s collection. Like the art form, the long time frame of 3,520 years the exhibition covered was in itself humorous but spoke to the practice’s history and versatility. Curator José Luis Blondet, in a video touring the exhibition, highlighted several pieces in dialogue with each other; referencing its religious roots, he paired a 1920s postcard of a woman holding a ventriloquist doll next to Aelbrecht Bouts’ Madonna and Child Enthroned (c. 1510), the compositions mirroring each other, dummy as baby Jesus and the girl as Madonna. Of course, Laurie Simmons was included in the exhibition; a piece consisting of a grid of photos, Girl Vent Press Shots (1989) is composed of photographs of headshots of female ventriloquists that Simmons saw at Vent Haven Museum, the only museum dedicated to ventriloquial memorabilia, located in Kentucky (and also the organizer of the famous international ventriloquist convention, which Becker attended in 2022).

Beyond her love of puppets, for Becker and her practice, ventriloquism provides a more open writing process, akin to the alter egos that many artists have historically created. “No one actually wants to do it—but the idea of ventriloquism resonates with so many artists—the idea of having someone else speak for you, or speaking for someone else, not knowing where your voice is coming from, or the multiplicity of the characters you might be and expressing them.”

0 Comments