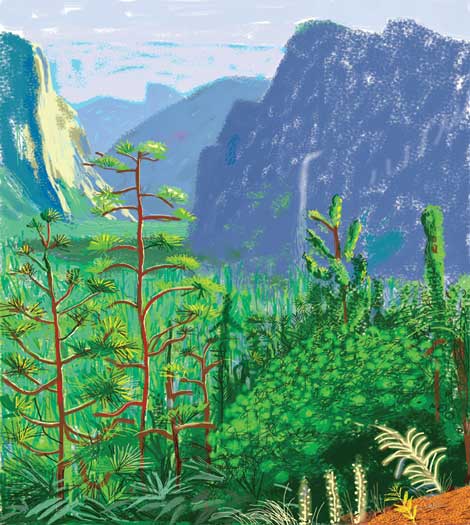

I attended the opening of a show of the recent work of David Hockney at the L.A. Louver gallery titled “The Arrival of Spring.” These colorful prints of the East Yorkshire English landscape were composed by Hockney on his iPad with an app that allowed him to create the “art work” from a digital palette with his fingers. The end product is truly Hockney-esque and it is not readily apparent that the work was not produced by using conventional printing methods. In previous years Hockney has produced art works of facsimile drawings, offset prints on a photocopier and computer-assisted images. These pricey iPad works (in limited editions of 10 to 25 each) were nearly sold out, according to the Louver staff.

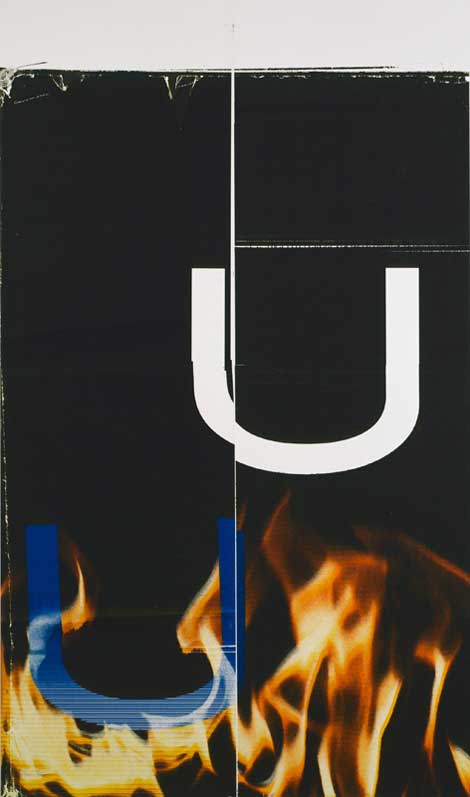

Other well-known artists such as Wade Guyton have produced highly regarded art work with digital formats such as scanners and ink-jet printers. Perhaps digital reproduction will be the wave of the future. Will we see a world in which artworks are ultimately distributed to collectors in digital format enabling them to print out (or not) files of the works in any way they see fit—be that on high quality paper or, indeed, toilet paper? The answer depends, in part, on whether the artists will be able to control the reproduction of their work, or risk losing control of it, as many musicians have in recent years.

Wade Guyton, Untilted, 2006, Collection of Nina and Frank Moore. Photo Lamay Photo. Copyright Wade Guyton.

Currently, under copyright law, the artist retains the copyright in a work even if the physical work is sold, unless the artist expressly conveys the copyright through sale or licensing. These are valuable rights enabling the artist to retain control of their images in book publishing and in merchandising and to prevent unauthorized reproductions of their works. Digital distribution may present a challenge to control via copyright, but the world becomes more digital daily and artists may seek mass markets for their work without regard to their copyrights as a way of building up their brand, a path Robbie Conal, for one, has blazed brilliantly.

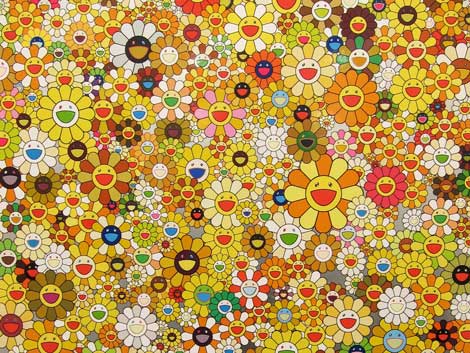

In our digital world, thousands of copies of the same image might be sold at a modest price so the artist can reap the rewards of mass-market sales. Should digitally distributed work be considered a work of art? Artists, as well as the general public, are often unaware that a “work of visual art” is defined under U.S. copyright law as “a painting, drawing, print or sculpture, existing in a single copy, in a limited edition of 200 copies or fewer that are signed and consecutively numbered by the author… ” (17 U.S. Code, Section 101). Therefore, mass digitally distributed works of art would not be recognized as “visual works of art” for copyright purposes, nor are limited editions of 200 or more copies of lithographic or serigraphic works. That doesn’t mean that artists and collectors should shun editions of higher magnitude. Multiple works by Jeff Koons, Takashi Murakami and other major artists are sometimes sold in editions of thousands for thousands of dollars apiece. Are they “works of art?” The resale market seems to indicate they are valuable and collectible so perhaps they should be considered works of art regardless of what the copyright statute says. However, collectors should keep in mind that the price rises on multiples rarely match those on a one-of-a-kind resale.

When digital editions go into the tens of thousands and beyond, the question of just what constitutes a work of visual art will loom larger. Eventually, the artist might not care about copyright at all, seeking to sell or even distribute, by means of a free app, mass quantities of art work at the push of a digital button and from there it will be a free-for-all as the “art work” goes viral. Other artists might be more concerned, especially if their artwork is incorporated into the work of another artist.

As we get deeper into the digital age and even artists as seasoned as David Hockney pioneer and propel these new formats, we peer into an uncertain future for artists and collectors. At the L.A. Louver show, I peeked into the director’s office and noticed a very large one-of-a-kind painting by Hockney of the Yorkshire countryside, astonishing in its composition and beauty, proving once again that a conventional work of art by an artist of Hockney’s stature cannot be exceeded digitally—even by Hockney himself.

,