The greatest collection of art in the world may not be at the Met or the Louvre any longer. The secret vaults of the wealthiest collectors in the world may hold much more art than the top art museums, with the vast majority of it locked away in so-called freeports in Geneva, Singapore, Monaco and Luxembourg. In 2015 Newark, Delaware, was designated as a freeport and now Wall Street titans don’t even have to travel overseas to visit their art collections. These freeports are places where goods can be shipped custom-duty-free. The most important freeport is in Geneva where an estimated 1.2 million works of art are stored. The Geneva warehouses offer fireproof state-of-the-art facilities with impeccable security.

The number one attraction of freeports is secrecy. Mega-collectors can buy works of art and hide them away until their value goes up. Then they can sell the works to another mogul right out of the vault and the buyer can leave it there with nothing more than a convenient clerical transaction. Freeports also provide tax avoidance. A buyer of an artwork at a California auction can ship it directly to a freeport and not have to pay any sales tax unless he brings it back to California, if ever.

There are concerns that some of the world’s greatest masterpieces will never be available to the general public. Most museum shows depend on curators assembling works from private collections, but these secret freeport stashes aren’t known to curators. The New York Times reports that 78 Picasso works are stored in the Geneva freeport by the stepdaughter of his second wife, Jacqueline, and that British collector/dealer Helly Nahmad has at least 4,500 works there.

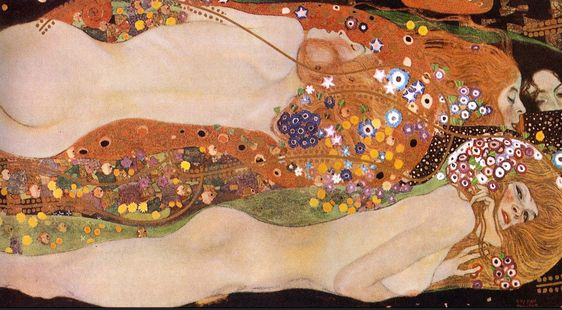

Gustav Klimt’s Water Serpents II

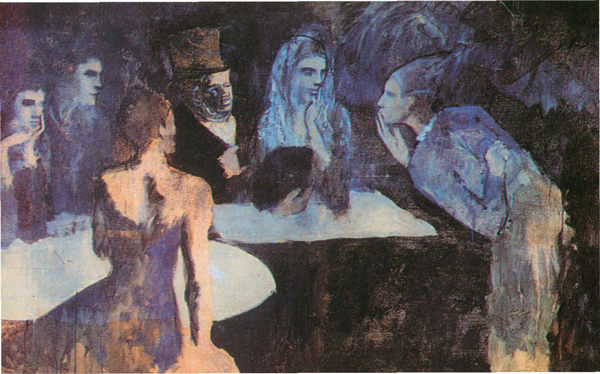

Major works have been bought or sold out of Geneva by one of the world’s richest collectors, the Russian mining oligarch Dmitry M. Rybolovlev, whose estimated $2 billion art collection includes Gustav Klimt’s astonishing Water Serpents II, Picasso’s blue-period Les Noces de Pierrette, and even a Leonardo—Salvator Mundi.

Rybolovlev is embroiled in a nasty dispute with one of the operators of the Geneva freeport, Yves Bouvier, whose company controls the freeport’s largest space. According to a February New Yorker profile of Bouvier, he began to act less as a warehouse operator and more as a dealer in recent years. Bouvier was instrumental in providing inside information about choice works Rybolovlev might wish to purchase since he knew when art in his warehouse was for sale. The mining baron claims he was being charged a flat 2% commission, but Bouvier says he was operating as a dealer and could take whatever cut he wanted to.

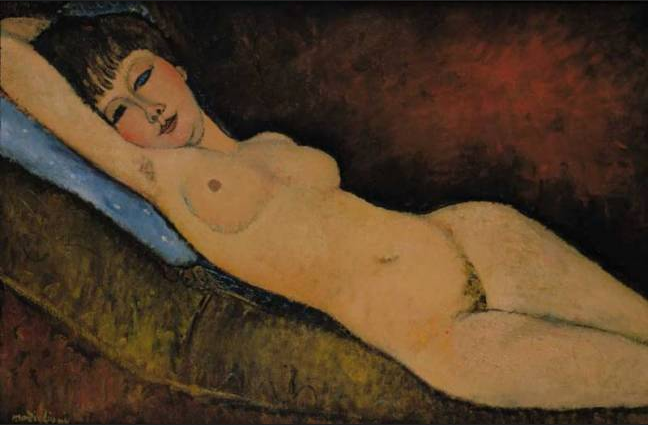

Modigliani’s Nu Couché au Coussin Bleu

Rybolovlev gave Bouvier wide latitude in building the billionaire’s collection for over 12 years. The pair originally met in Switzerland where Rybolovlev relocated his family before his arrest in Russia on charges of contract murder of a business rival, spending a year in prison before being cleared. In 2010 he sold his shares in his mining company and his collecting went into high gear. It’s speculated that the oligarch needed the freeport to hide assets from his ex-wife and her lawyers in what may be the most expensive divorce case ever. That same year Bouvier opened the most elaborate and secret freeport facility in Singapore, which cost a reported $100 million, undoubtedly financed by the money he was making from Rybolovlev.

It was Bouvier who located Klimt’s Water Serpents II and sold it to Rybolovlev for $183 million, making a profit estimated at $60 million. Bouvier arranged the sale of the Leonardo for $127.5 million to the billionaire. But the sale that blew Bouvier’s game was his purchase of Modigliani’s spectacular nude, Nu Couché au Coussin Bleu, from one of the richest American collectors, hedge-fund king Steve Cohen, and its prompt sale to Rybolovlev for $118 million. Around Christmas, 2014, Rybolovlev, vacationing in St. Barts, had dinner with Sandy Heller, an art consultant whose star client was Cohen. Heller told him that the price Bouvier paid for Nu Couche was $93.5 million. Rybolovlev was stunned and instantly realized he had been ripped off by Bouvier.

Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi

In February, 2015, Rybolovlev convinced the authorities in Monaco to arrest Bouvier for fraud and money laundering. Though Bouvier was released after a few days in jail, his troubles were just beginning. Rybolovlev filed lawsuits all over the world attempting to seize Bouvier’s assets, claiming that Bouvier had defrauded him of hundreds of millions of dollars.

Bouvier complains in The New Yorker that major dealers consider him nothing more than a warehouseman who has meddled in their rarified air. He claims the top dealers have their own inherent conflict, since they control valuable inside information about buyers and sellers in their own gallery business.

In November, 2015, Rybolovlev resold Modigliani’s Nu Couche at Christie’s for $170 million, making it hard to feel too sorry for him. That same month, Switzerland passed legislation making its freeports more transparent. In February, 2016, a court in Monaco ruled against Bouvier’s pre-trial legal challenge to criminal charges, so the case may now proceed. Meanwhile, much of the world’s artistic heritage remains secreted in dark climate-controlled warehouses— safe, but unseen.