Stefan Simchowitz is a controversial figure in the art world. He doesn’t own an art gallery yet maintains a large network of art collectors. He eloquently expounds upon art theory but is not associated with an art institution. He provides advice and monetary support to numerous artists whom he claims to have discovered but isn’t a conventional art patron. He doesn’t like to be called an art dealer, but that is basically how he operates. The New York Times Magazine did a profile of Simchowitz early last year, in which they named him the “Patron Satan” of the art world. Simchowitz, who infamously appeared clad only in briefs in a photo accompanying the Times piece, told me that the article is “a work of fiction” typical of the Times’ “bias” against the Los Angeles art scene.

The controversy surrounding Simchowitz has only gotten deeper. In June, 2015, Simchowitz’ company, Simcor, and an associated dealer, Jonathan Ellis King, filed a multi-million-dollar suit in federal court against a young Ghanaian artist, Ibrahim Mahama, who Simchowitz claimed to have discovered on the Internet, comparing him to the red-hot Oscar Murillo, whose works Simchowitz bought early and resold to his group of collectors. Simchowitz is proud of discovering new artists: “No one knows about these artists. There is no market for their work. By providing capital to young artists they have a better opportunity to compete,” he told me in a recent interview about the lawsuit.

Ibrahim Mahama, Civil Occupation, installation at Ellis King gallery, Dec 2014.

Mahama’s signature medium for his artworks are jute fiber sacks used in Third World countries as receptacles for commodities from cocoa to charcoal. The artist acquired the soiled sacks for next to nothing and had them sewn together, creating quilt-like works. An installation called “Civil Occupation,” sponsored by Simchowitz and King in King’s Dublin art gallery covered its entire floor and walls during a December, 2014 show. The hundreds of sacks created a mournful cathedral in somber hues of browns and rusts, perhaps an ode to the forgotten laborers of Third World commodities trade who often leave their names or marks upon these sacks.

In the lawsuit, the dealers allege that they made an oral contract with Mahama to pay him about $148,000 in exchange for a large amount of the sacks the artist had assembled. They say some of the sacks were to be used in the gallery installation, the rest were to be made into smaller works mounted on stretchers, a process costing the dealers $67,000. The legal complaint claims that just prior to the gallery show Mahama signed 294 of the works at King’s gallery. The dealers allege they sold 27 of the pieces to collectors for $16,700 each, therefore valuing the remaining 267 works at $4.45 million. They claim Mahama breached the contract by directly selling 20 of the works to an LA collector to finance a massive jute-sack installation for the 2015 Venice Biennale that ran for 300 meters through the “All the World’s Futures” exhibition. It has been reported that an Italian gallery, A Palazzo, currently representing the artist, also provided financing for the Venice installation.

The lawsuit, alleging causes of action for breach of contract, fraud, commercial disparagement, and unfair competition, was filed after Simchowitz and King received correspondence from Mahama informing them that the 294 stretcher works were not authentic and could not be sold since he never agreed to the “commercialization” of his works. Mahama also claimed ownership of the installation displayed at the King Gallery.

Simchowitz told me he spent two years on the Mahama project. “He was using jute coal bags made by migrant laborers for pennies. We assisted him in repurposing them and now they hang on gallery walls as valuable art works.” Simchowitz claims that the A Pallazo Gallery interfered with his relationship with Mahama and told him that Simchowitz was “evil.” He said this was an example of “artists using my money and galleries giving them bad advice.”

Stefan Simchowitz, photo by Rosi Riedl.

Simchowitz says he had at least 20 pending deals for sales of Mahama’s works to clients, but now those “deals are dead” and his reputation has been damaged. “Mahama thinks: ‘I’m morally justified to screw you cause you’re Satan according to The New York Times.’” He called Mahama “a two-faced liar” who “forced my hand and I had no option but to sue.”

I also spoke with Mahama’s lawyer, Rizwan Ramji, who told me a much different version of events. He said that Simchowitz did not “discover” Mahama—instead Ellis King attended a London show of Mahama’s work in 2013 and met the artist at the Frieze London art fair and it was only after a deal was made with King’s gallery for a show that Mahama learned that Simchowitz was the principal financier behind King. Ramji said that Mahama shipped four large packages of jute sacks from Ghana to King’s gallery and some of those shipments were used when the works were cut onto stretchers. The lawyer says that Simchowitz “intimidated” the artist into signing the backs of the stretchers for each of the works “under duress.” He says Mahama didn’t care for Simchowitz who is “used to using his money to get his way.” He says that as a result of the lawsuit, the A Palazzo gallery must use letters of authenticity when they sell Mahama’s works.

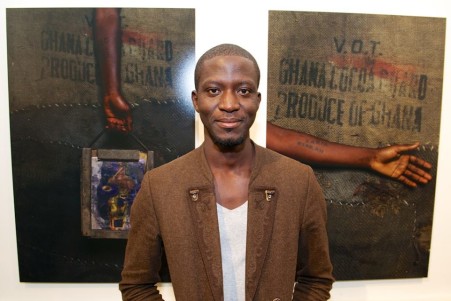

Artist Ibrahim Mahama at A Palazzo Gallery, Booth G11 East Wing © Sébastien Gracco de Lay

As for the lawsuit, Ramji said that he will file a cross-complaint on behalf of Mahama for breach of contract and violation of the artist’s rights of publicity, including using his name and likeness without his permission. Mahama may also claim violation of his rights of droit moral, since Simchowitz “destroyed the integrity” of his artworks by ordering them cut into hundreds of smaller works.

Simchowitz takes a dim view of many of the other artists he has worked with. He told me that many prominent artists, such as Sterling Ruby, are “careerists” who are “consumed with money.” He adds, “The avant-garde is dead. Artists have been mythologized, but they are not cutting off their ears or going off to Tahiti anymore. Artists think they have moral rights and can just breach contracts.” He is furious with former artists he’s represented such as Parker Ito and Christina Rosa, claiming their “careers crashed” after they left him. He also mentioned artist Torey Thornton whom he has openly threatened to sue.

Simchowitz, who has been banned from a number of galleries, sees his role as “flattening hierarchies” in the art world. “Galleries protect their legacy systems, but this doesn’t work anymore—we’re in a different world,” he says.

Simchowitz clearly sees himself as a maverick out to smash the prevailing art-world paradigm of major collectors, multinational galleries and big auction houses that set the ground rules of the art world. This may be an admirable goal, but whether or not he succeeds in creating a new paradigm, his version of the art world will still be about the money and consequently some of the artists he “discovers” will probably continue to look for a bigger and better deal.