In April I received a catalog for Sotheby’s May 2015 contemporary art auction with a cover image of a cardboard Coca-Cola crate embossed in gold leaf, an artwork created by Danish artist Danh Vo. This untitled 2011 work sold at that auction on May 13 for $466,000. I was puzzled by the hype for Vo since I thought this territory was covered in the ’60s by Andy Warhol and his Brillo boxes. I was further stunned when I discovered that a similar though larger work, Alphabet L, essentially a carton flattened into an “L” shape, also from 2011, sold at Sotheby’s May 15 evening auction for $700,000. The seller who admitted reaping a huge profit on Alphabet L was Bert Kreuk, a wealthy Dutch art collector.

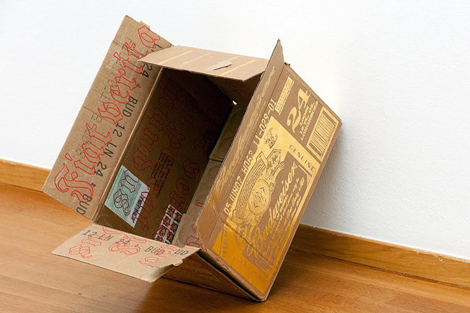

Within a month of Kreuk’s sale of Vo’s work at Sotheby’s, a Dutch court handed him a victory in a lawsuit he had filed in the Netherlands against Vo. Kreuk claimed in his lawsuit that he had a 2013 oral contract with Vo for a commissioned installation at the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague for a fee of $350,000—a job that Vo never completed. The court ruled that if Vo doesn’t finish the installation he will be fined over $390,000. Vo vowed to appeal the ruling. The case involved a gold-leaf Budweiser carton titled Fiat Veritas (Let There Be Truth) which Vo claimed he only lent to the exhibition. Even though there was no written contract, the court recognized that the agreement was binding after reviewing numerous communications between the parties. The Vo piece was one of Kreuk’s collection of 62 works displayed at the show, ranging from de Kooning to young hyped artist Oscar Murillo. Kreuk claimed Veritas was just one of a number of Vo works he had commissioned to create for the exhibition. Kreuk suspected that Vo didn’t follow through because he realized that he could make much more by selling the works individually.

Kreuk also created controversy about his role as guest museum curator when he sold 11 of the works at auction at Sotheby’s shortly after the exhibition, including one by Vo, for a handsome profit. This is a controversial practice in which museums are becoming the willing “partners” of major collectors, apparently hoping to curry favor with them when these collectors decide to make gifts or bequests of artwork.

Vo is among the young so-called “early blue chip artists” whose works are subject to wild price speculation at auction. The New York Times reports that his art sales proceeds at auction have rocketed from $33,700 in 2012 to $2.37 million this year. Some of the other artists in this group include Murillo, Dan Colen and Lucien Smith. Vo has openly objected to collectors “flipping” his works to make a quick buck. The practice of flipping is becoming more central to the auction world each year. This May’s auctions by Sotheby’s and Christie’s were rife with works by the early blue-chip art stars. These works have gone up exponentially, sometimes even in the year of their creation. It used to take at least 10 years to “season” a work price-wise; now some works are flipped while the paint is still fresh.

Kreuk’s flipping infuriated Vo. He made no bones about not wanting to create any more work for Kreuk at the original contract prices only to have Kreuk immediately sell the work at auction for huge profit. Vo was quoted in the Times as saying, “If they only look at my work as a commodity, then that is something I am not interested in… I don’t think I can work like this. I don’t think anything can come out of me because there is such a deep resistance. It goes against everything I believe as an artist.”

The rampant speculation in the art world may have a downside too. If the stock market were suddenly to crash, history shows that the most rapid declines in the value of artwork would come from works by newbie art stars. We’ve seen this happen before as art darlings of the ’80s, many of them from the original Mary Boone Gallery—Schnabel, Salle, and Fischl—fell out of favor abruptly in the ’90s, before making a comeback in recent years.

The Dutch court ordered the Veritas piece to be held as collateral to make sure Vo pays the legal fees awarded to Kreuk. In July Vo proposed a vulgar solution to his court-ordered commission for Kreuk. In a letter sent to artnet news and widely circulated on the net, Vo offered to install, in both Kreuk’s residence and in the Gemeentemuseum, a site-specific wall work repeating a line that was uttered by the demon in The Exorcist film “to the extent it will become as impressive and large as you find fitting for the amount of $350,000: Shove It Up Your Ass, You Faggot.”

Vo asked Kreuk for a written reply. Kreuk replied to Vo in artnet in a letter approved for public release: “This whole case is so bizarre it is unbelievable. It is like I landed in some kind of surreal world. Artnet had Danh Vo’s letter before I did. The court ruled that both parties should be in touch with each other in a ‘professional way’ and to ‘normalize relations.’ I do not think this type of behavior is what the courts meant by that.”

One of the lessons of this lawsuit is that, if a collector commissions a work, he should make sure that he enters into a written agreement which specifies as precisely as possible what the commissioned work is expected to be like. Otherwise, conceptual artists like Vo may well have the last laugh.