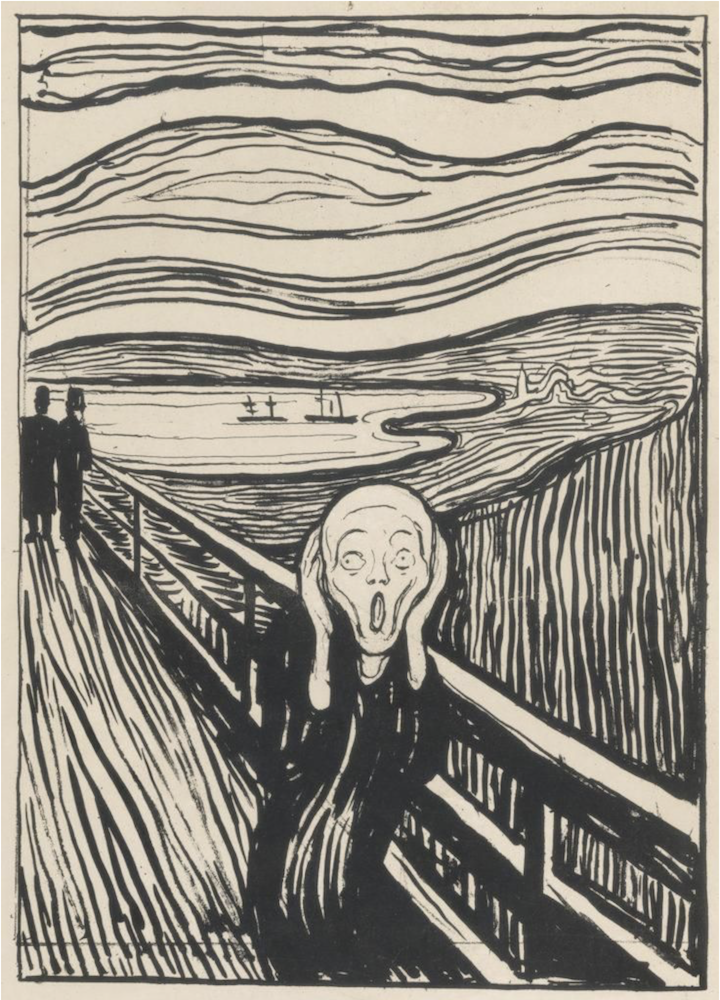

Billionaire founder of private equity firm Apollo Management, Leon Black, was at the top of his game in 2021 both as a Wall Street financier and as one of the world’s leading art collectors, owning works valued at more than $1 billion (he paid $120 million for a version of Munch’s The Scream). But by the end of that year, Black stepped down as chairman and CEO of Apollo and as the Museum of Modern Art’s board chairman.

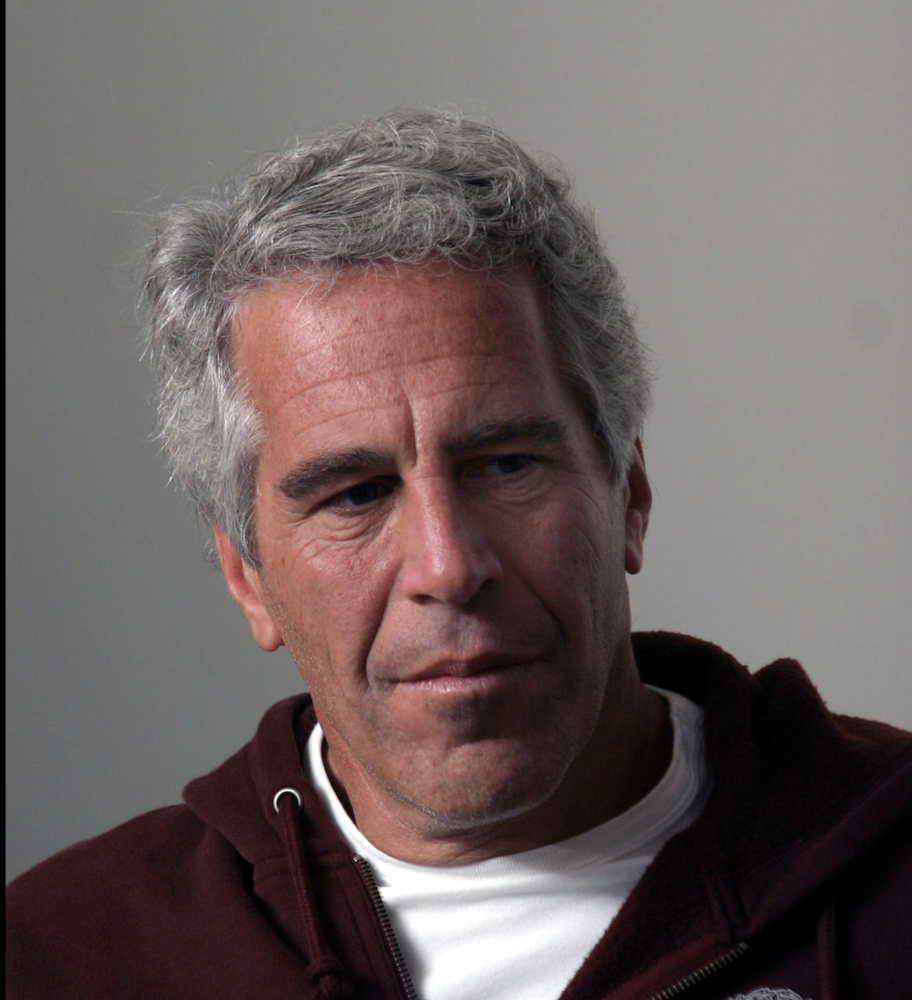

Black’s association with reviled child trafficker Jeffrey Epstein was the cause of his fall. Since 2021, three women have accused Black of rape in connection with his relationship to Epstein (one case was dismissed last May). In January 2023, Black paid $62.5 million to the U.S. Virgin Islands to settle claims relating to Black’s involvement with Epstein. Black had visited Epstein’s private island in the Virgins several times. The islands had threatened a lawsuit against Black for facilitating Epstein’s nefarious operations by paying millions to his companies chartered there for tax advice.

It has been reported that Black and Epstein, the latter found dead in his prison cell in 2019 while awaiting trial, were close friends as well as business associates. In 2020, Dechert, a law firm hired by Apollo to investigate Black’s dealings with Epstein, found that from 2012 to 2017, he paid Epstein $158 million—an astonishing amount for “tax advice.” No law firm or accounting company in the world charges an individual anything near those fees for tax consultation.

Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1893.

In July 2023, the Senate Finance Committee, investigating sophisticated tax schemes used primarily by the top 1% to avoid payment of billions in taxes, sent a 16-page letter to Black asking him to provide responses and documents to numerous questions. One of the committee’s key inquiries was whether Black originally deducted the $158 million he paid to Epstein, who had advised Black that he could do so, and if it should have been classified as a gift subject to taxation.

Dechert also found that Black had used a loophole in the IRS code to avoid more than $2 billion in gift and estate taxes in conveying assets to his children through GRATs (grantor retained annuity trusts), complex devices which allowed Black to retain income from a trust while placing it in trust for his heirs. Epstein—neither a lawyer nor a CPA—claimed to Black that he had invented a “proprietary” method for setting up GRATs.

In addition, Black availed himself of another tax avoidance device, a 1031 exchange which was originally devised under the tax code to permit delayed payment of capital gains taxes on like-kind sales and purchases of commercial real estate.

Until the IRS nixed them for personal property in 2017, 1031 exchanges were also used to shelter like-kind exchanges of artwork from capital gains. The main advantage of 1031 exchanges was that a collector could buy and sell art and avoid paying capital gains taxes for years. A 1031 exchange requires a third party to qualify the transaction as “arms-length.”

This past October, The New York Times reported on a 1031 artwork exchange designed and executed by Epstein for Black. On November 23, 2016, Black sold a Giacometti sculpture for $25 million to the Haze Trust (controlled by Epstein, not known to be an art collector), and on the same day a company controlled by Black bought a Cézanne painting for $30 million using the proceeds of the Giacometti sale. The Times uncovered the fact that the day before the sale, Epstein had wired money from a larger account, the Southern Trust, to the Haze Trust. The Southern Trust was a vehicle that Epstein used to collect fees paid to him by Black, making it appear to be a self-dealing transaction. However, Black’s use of Chicago Deferred Exchange Company, which specializes in providing third party services for 1031 exchanges and which created the companies in the transaction, may provide him with some cover.

Jeffrey Epstein.

A similar transaction between Black and Epstein involving a Braque and another Cézanne was also identified by the Times. While the paper says that both the Giacometti and the Braque were sold at auction in 2017, it could not identify the sellers or buyers.

Much of the Senate Finance Committee’s demand for detailed information from Black is still outstanding. Black’s responses in September to the committee’s July letter were found to be largely inadequate. Hopefully, the chairman, Senator Ron Wyden, will continue attempting to unravel the mystery surrounding the Black-Epstein dealings.