The Gagosian Gallery in Beverly Hills had its annual Oscar week art opening in February with an after-party for its top Los Angeles patrons at nearby Mr. Chow’s. The show this year was a selection of eye-popping oil paintings by John Currin depicting Rubensesque young women in various states of undress—mostly in lace negligees. Among the well-dressed crowd, I noticed such celebrities as Elton John, Leonardo DiCaprio and Mick Jagger. Standing prominently near the front door was dapper proprietor Larry Gagosian, in his perpetual tan and bespoke suit, displaying one of the biggest smiles I’ve ever seen. One can only wonder if Gagosian’s grin was due to his December, 2014, court victory over mega-billionaire art collector and Revlon chairman, Ron Perelman, (whose art collection has an estimated value of $1 billion) who had sued him for fraud in a New York court.

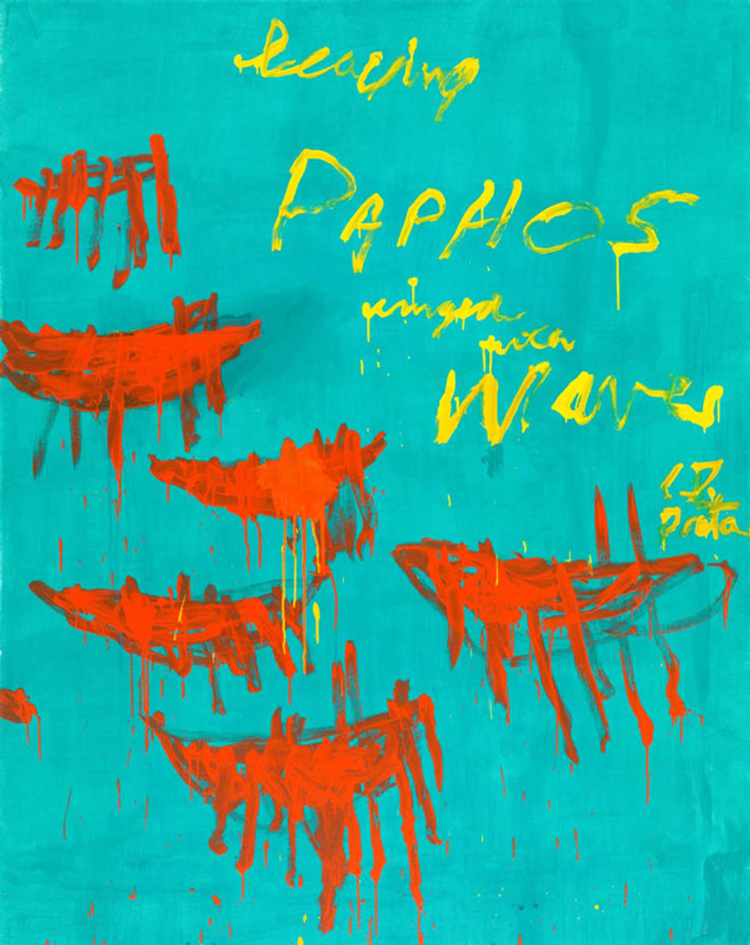

Gagosian was one of Perelman’s primary dealers and their association and friendship dated back at least two decades. But filing lawsuits is routine business for the litigious Perelman. Gagosian may not be as blasé, considering the huge legal fees involved in the case. In April, 2011 Perelman asked Gagosian for a price on a 2009 Cy Twombly painting, Leaving Paphos Ringed with Waves. Gagosian asked $8 million and Perelman offered only $6 million, so Gagosian sold it to the Mugrabi family, also super-rich collectors. A few months later—Cy Twombly in the meantime, having died that July—Perelman again approached Gagosian about buying the Leaving Paphos piece. Gagosian now offered him the painting for $11.5 million and ultimately sold it to Perelman for $10.5, giving the Mugrabis a quick profit with Gagosian reportedly snagging a $1 million commission.

In September, 2012, Perelman filed suit alleging that the sale was fraudulent and that Gagosian breached his fiduciary duty as an art dealer to him. Perelman stated in the suit (MAFG Art Fund, LLC v. Gagosian) that he relied on Gagosian’s “unparalleled knowledge and dominant position in the art world.” The sale to Perelman was partly consummated in cash but also through an exchange of artwork from Perelman’s trove, including a Koons Popeye sculpture which Gagosian valued at $4 million and paintings by de Kooning and Lichtenstein. Perelman claimed Gagosian considerably undervalued these works. Perelman did extensive legal discovery possibly intending to make this case into an exposé of alleged non-transparency in pricing by major galleries in the resale market, but he didn’t get very far. While much of the art world was at Art Basel Miami Beach last December, word quickly spread through the exhibition floor that Gagosian had won the case in a unanimous New York appeals court decision which upheld a lower court ruling dismissing Perelman’s claims.

The New York court in its brief written decision based its finding on a line of cases holding that a statement of value, even by a trusted art advisor or gallerist, is “non-actionable opinion” despite its possible lack of accuracy. The court held that Gagosian did not have a fiduciary duty to Perelman (who used limited liability companies to purchase art) who the court found was a sophisticated art collector: “The complaint does not establish that defendants exercised control and dominance over plaintiffs—limited liability companies who, by their own description, frequently purchased, sold and exchanged works of art as investments.” The court further found that Perelman, as a major art player, needed to do his own vetting: “These sophisticated plaintiffs cannot demonstrate reasonable reliance because they conducted no due diligence; for example, they did not ask defendants, ‘Show us your market data.’ ” A word of caution: the decision could still be appealed to a higher court, but it seems unlikely that it will be overturned considering the ample judicial precedent for its holding.

There were two similar cases decided by New York courts in 2011 involving wealthy buyers and prestigious galleries (one against the Wildenstein Gallery) and millions of dollars of artwork. In both cases the courts absolved the art dealers of liability when sued by collectors for fraud for allegedly inflating prices. The courts held that the dealers were merely giving “opinions” which could not be the basis for claims of fraud.

For cases involving fraud claims based on allegations of intentional misrepresentation, California recognizes that the representation must ordinarily be an affirmation of fact, as opposed to opinion. California Civil Jury Instruction No. 1904 states that a representation is an opinion: “If it expresses only (a) the belief of the maker, without certainty as to the existence of a fact; or (b) his judgment as to quality, value, authenticity, or other matters of judgment.”

So California dealers may rely on giving opinions to buyers that are based on beliefs or their judgment, not statements of fact. However, I would caution that when dealing with novice collectors in the resale market it is best for galleries to be careful to make sure that the buyers understand that dealers are giving them opinions in valuation, not absolute fact-based pricing. Most case law in this area has involved litigation by wealthy or sophisticated collectors. However, courts may not be as forgiving to dealers who are alleged to have mistreated mere mortals.

As the Gagosian Beverly Hills gallery show wound down and the VIPs and major collectors walked over to Mr. Chow’s for the dinner Gagosian was hosting, Ronald Perelman was—the Revlon czar must have considered their differences more than cosmetic—nowhere to be seen.