In September during a visit to Paris, I got lost in the Louvre, a common occurrence caused by its diabolical mazelike layout (maps are useless) and I found myself in the museum’s Oriental Antiquities wing. After viewing hundreds of paintings in the French and Italian rooms, I’d had enough art, so I turned around for the exit, which is why I failed to notice an alteration to the plaque on the wall, a blackout of the Sackler family name—chief benefactors of the Asian wing.

If you haven’t heard of this family, or viewed the Met’s massive Egyptian Temple of Dendur in its Sackler wing, the Sacklers are among the most generous donors to the world’s art institutions. However, they are also owners of America’s third-largest privately held company, Purdue Pharma, infamous for having held patents on OxyContin and other opioids which have caused the untimely deaths of thousands. This makes them one of America’s most controversial families.

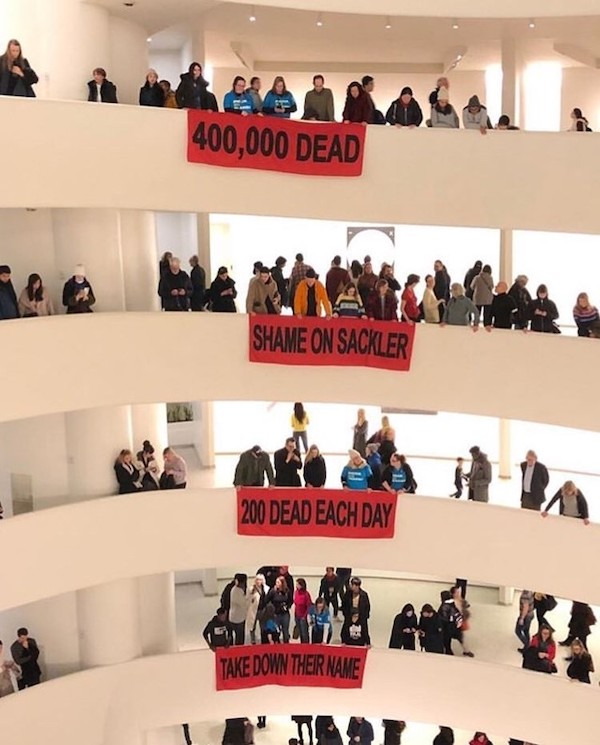

Nan Goldin protest.

Purdue was acquired by three Sackler brothers in the 1950s and management now encompasses their third generation. The Sacklers have been accused of trying for years to cover up OxyContin’s addictive nature. Some of the Sackler heirs have little to do with Purdue and, according to the New York Post’s Page Six, a Sackler couple recently decided to sell their $6.5 million townhouse on the Upper East Side, after being shunned by high society, only to decamp to Palm Beach (pauvres petites choses).

The Sackler controversy roiled the art world for much of this year. There have been demonstrations at the Met and the Guggenheim—which have received millions in donations from the Sacklers. The most notable took place in the Guggenheim rotunda, where protesters lined its famous spiral walkway and rained down hundreds of dummy prescriptions for OxyContin “signed” by Purdue’s chairman, Richard Sackler. The protest was organized by artist Nan Goldin who has battled addiction and who prostrated herself on the rotunda floor. The crowd unfurled banners reading, “Shame on Sackler—Two Hundred Dead Each Day—Take Down Their Name.”

Nan Goldin protest.

So far, only the Louvre has taken down the Sackler name (although the Met announced it will turn down future donations from the Sacklers). The reason American museums have balked at removing the Sackler name may be related to contractual restrictions—a multi-million-dollar donation is often accompanied by a contract tying the donation to naming rights to a physical location in the building in perpetuity. If the donor’s name is removed, then the donation may be revoked or cease.

The Sacklers are not the only art patron family coming under fire for where their fortunes come from. The ultra-conservative Koch family (owners of America’s largest privately held company—Koch Industries) have long been major and controversial donors to the arts. David Koch, who recently passed away, was a fixture at the Met’s most glamorous functions. Koch Industries’ main business is petro-chemical processing; and the Kochs are big time climate-change deniers. The renovated area adjacent to the imposing Met entrance stairway was recently named David Koch Plaza (its unveiling drew protesters).

Nan Goldin protest.

One of the strongest protests occurred this summer against Whitney trustee Warren B. Kanders, a major donor. Kanders’ “crime” is that he owns Safariland, a manufacturer of police and military supplies. Apparently, some Safariland tear gas grenades were used against protestors at the Mexican border. After eight artists pulled out of the 2019 Whitney Biennial in protest, Kanders issued a letter of resignation..

The problem of dirty money and its influence on the art world is nothing new. After all, the Getty Museum and Villa rely on the immense fortune of legendary oil baron J. Paul Getty. The Hammer Museum in Westwood is named for the late chairman of Occidental Petroleum, Armand Hammer.

The real question is where to draw the line. As government funding for the arts continues to decline, art institutions rely more heavily on private donations. Naming rights are an established way to loosen the wallets of the wealthy. Should the Koch’s millions be denied the Met because they are climate-change deniers who may be whitewashing their money? How was the Whitney supposed to know Kanders’ company manufactured tear gas grenades that would be used against peaceful protestors? There are no easy answers.