“Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World”—intended to be the most important show of Chinese dissident art in recent years—limped into California late last year. The show traveled to the Guggenheim Museums in Bilbao, Spain and New York before its display at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. The namesake of the show and the first piece on display—Theater of the World (1993) by Huang Yong Ping and two other works were censored by SFMOMA, which claimed it was following the lead of the New York Guggenheim’s controversial decision to pull the works due to “serious” security threats received after PETA and other animal rights groups vehemently protested.

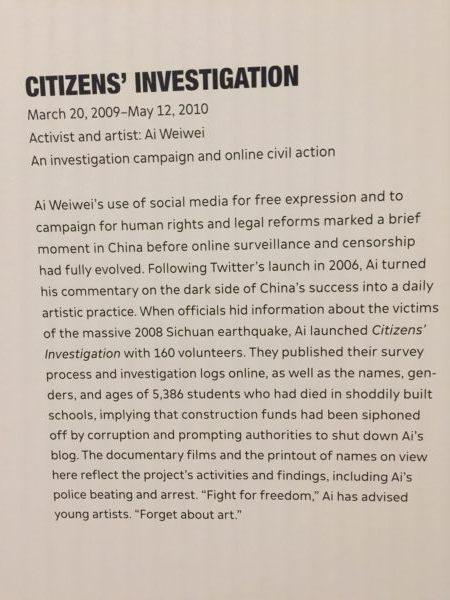

There are a number of striking works of dissident art in the show including Cao Fei’s Whose Utopia (2006), a video of numbing repetitive tasks performed by workers at a light bulb factory in Guangzhou, China, Cai Guo-Qiang’s gunpowder mushroom-cloud works, and Ai Weiwei’s somber display of a wall-size register of his “citizen’s investigation” exposing the suppressed identities of the 5,386 children who died when their shoddily constructed schools collapsed during the 2008 Sichuan earthquake—an event that was heavily covered up by the Chinese government.

However, the censorship issue casts a pall over the entire show. Upon entering the first room, visitors are confronted with two large empty hand-made terrariums carefully crafted by Huang intended to contain his Theater of the World. They were originally meant to be filled with a variety of insects and reptiles which would fight for dominance of their miniature world—perhaps a parable of the human struggle for survival (Huang referenced Thomas Hobbes’ philosophy as an influence). We are greeted with a plaque containing the “artist’s statement”: “It is a ‘living’ work in the truest sense, as there are living insects inside. But this work has repeatedly encountered ‘premature death’ without ever having a chance to ‘live.’ … [It] is said that more than 700,000 people are opposed to this work [through an online petition circulated at the time of the New York opening] that involves living animals; but how many of those people have really looked at and understood this work? …Everyone can express their views, but unfortunately their views are too often mere repetitions of others’ views.”

A second censored work, Xu Bing’s A Case Study of Transference (1994), is a video showing two pigs that the artist stamped with lettering—one with Roman lettering and the other with made-up Chinese characters—mating in a pen while spectators watch.

A curator’s statement situated next to the blank video screen says that the pigs copulate “ …in an allegorical, nonsensical meeting of East and West. For Xu …the performance was a literal and visceral critique of Chinese artists’ desire for enlightenment through Western cultural ‘transference.’ …This work has gone on to become one of the seminal images of experimental art in China during this period, and Xu has since received honors in his adopted U.S. home—including a MacArthur Fellowship …” The curator considers it “a seminal work” and yet we can’t even view it.

The third censored work, Dogs That Cannot Touch Each Other (2003), by Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, is a disturbing video of tethered pit bulls that face each other on treadmills. SFMOMA placed a statement next to the blank monitor: “When the [Guggenheim] was planning this exhibition in 2017, it received repeated threats of violence in response to the role of animals in the creation of this artwork. In consultation with the artists, the Guggenheim left the video documentation in place but turned it off. SFMOMA has chosen to replicate this modification to acknowledge the fact that the tension between political activism and animal rights is now part of the history of the artwork.”

This museum statement is absurd—an artwork should speak for itself. An artwork should not be replaced by a statement claiming that controversy “is now part of the history of the artwork.” The “history” of the dispute should be left to news reports. This statement is a bad precedent for the way museums should handle attempts at censorship that may become more frequent now that online petitions are in vogue.

A spokesperson for SFMOMA, Jill Lynch, assured me that the threats of violence against the Guggenheim were “very serious,” but would not go into detail because of “security issues.” It may be necessary to increase security at art museums, including the use of metal detectors, due to the coarse times we are living in, with internet trolls running amok spreading misinformation. These may be costly measures, but the mission of these institutions is to preserve artistic freedom above all else, not to bow to mob rule.

Ironically, a major show focused on dissident Chinese art by artists who may have risked their freedom and their lives for the sake of art has devolved into a fiasco in which America, the supposed paragon of artistic freedom, has engaged in wholesale censorship of these brave artists.