Salvator Mundi, a portrait of Christ attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, was sold to a Saudi Arabian prince for $450 million (including fees) at Christie’s New York auction last November, smashing the previous art sale record by more than a factor of two. Christie’s placed it in the middle of a major contemporary art auction to ensure that the world’s richest buyers would take note.

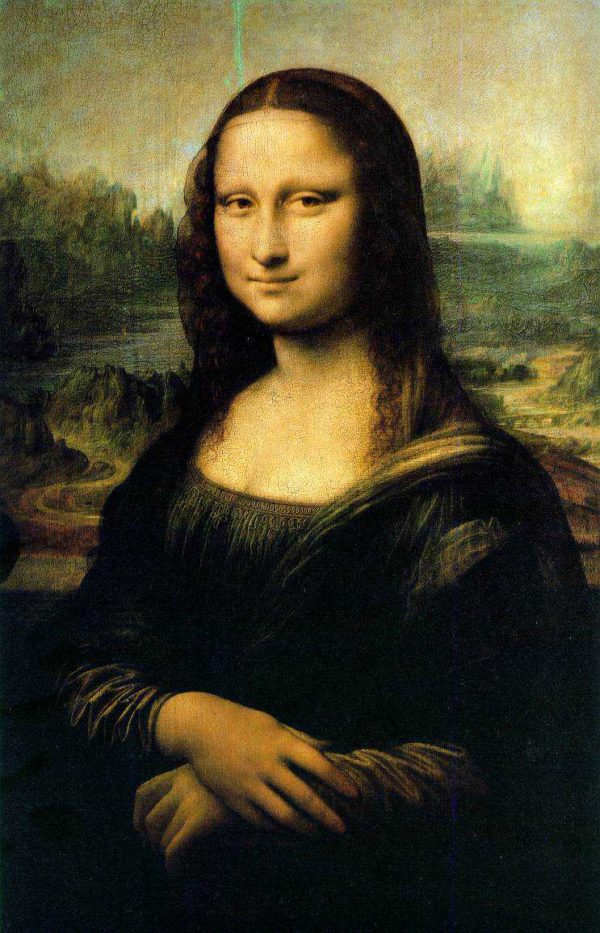

I’ve seen almost all of the 15 or so known Leonardo paintings and numerous original drawings up-close and personal and I am not alone in expressing substantial doubts that Salvator Mundi is an authentic Leonardo. I believe it is probably one of about 20 contemporaneous copies by Leonardo’s studio assistants, protégés or pupils. Flat and lifeless, with the frozen gaze and frontal positioning characteristic of late-Middle Ages icons, the work lacks the lively spirit and style of Leonardo and Sandro Botticelli that helped revolutionize portraiture in the late 15th century, exemplified by the Mona Lisa and Lady with an Ermine.

Leonardo da Vinci, Lady with an Ermine, 1490

Attempting to buttress the house’s claims of Leonardo’s authorship, Christie’s published a lengthy catalog essay and a detailed chronology. However, the history can’t hide Salvator Mundi’s troubled provenance. It’s generally acknowledged that Leonardo painted a portrait of Christ around 1500 and may have worked on it over a number of years, as was often his practice. According to the catalog, when French princess Henrietta Maria married King Charles I of England in 1625 she brought the Leonardo with her; it was listed in the 1666 inventory of Charles II. Christie’s speculates that it passed to the mistress of James II, Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester, after 1688, and then “by descent until the late 18th century.”

Christie’s catalog states, “Having vanished for around 200 years, the painting surfaces when it is acquired from Sir Charles Robinson as a work by Leonardo’s follower, Bernardino Luini, for the Cook Collection, Doughty House, Richmond.” Christie’s notes that by 1900 the work was already “extensively overpainted.” In 1913 an expert who authored a Cook Collection catalog claims it is “a free copy after Boltraffio.” Attribution to Leonardo’s pupil Giovanni Boltraffio is the current position of those art experts who dissent from the Christie’s view. On the dispersal of the Cook collection in 1958, it is sold at auction for less than $100, and “then disappears once again for nearly 50 years.”

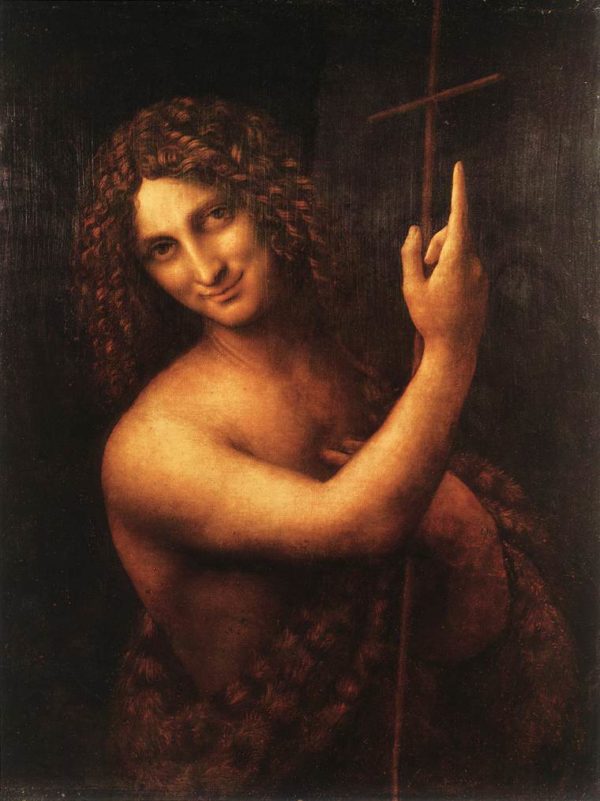

Leonardo da Vinci, St John the Baptist, 1513-16

In 2005 Salvator Mundi miraculously reappeared, according to Christie’s “masquerading as a copy” in a regional U.S. estate sale. Christie’s catalog says, “…its new owners move forward with care and deliberation in cleaning and restoring the painting, researching and thoroughly documenting it, and cautiously vetting its authenticity with the world’s leading authorities on the works and career of [Leonardo].’’ A restoration is undertaken by the Institute of Fine Arts at N.Y.U. “Technical examination and analyses demonstrate the consistency of the pigments, media, and technique discovered in the Salvator Mundi with those known to have been used by Leonardo, especially in comparison to the Mona Lisa and St. John.”

Christie’s says that it was studied over three years by a number of the world’s art scholars and that an “unusually uniform scholarly consensus that the painting is an autograph work by Leonardo” includes “its manifest superiority to the more than 20 known painted versions of the composition.” In 2011 the work was “unveiled” in the Leonardo exhibition at The National Gallery in London.

Not surprisingly, Christie’s omits the notorious dispute between the painting’s last two owners (described in my September, 2016 Art Brief column). Freeport mogul Yves Bouvier, who acquired the painting for $80 million in a private sale arranged by Sotheby’s, quickly resold it to Russian mining oligarch Dmitry Rybolovlev for $127.5 million in May, 2013.

the Mona Lisa, 1517

Bouvier was alleged to have woefully misrepresented the prices he paid for numerous trophy artworks he “flipped” to Rybolovlev. When Rybolovlev discovered the Swiss dealer’s ruse, he sued, and had him arrested on criminal charges in Monaco. Perhaps Rybolovlev—having realized a $300 million profit on November’s sale—will now settle with Bouvier.

Even the Saudi piece of this puzzle has an interesting coda. In December, 2017 the buyer of Salvator Mundi was revealed to be an unknown Saudi named Prince Bader. Days later, it was revealed that Bader was a straw buyer for Mohammad bin Salman, the 32-year-old crown prince of Saudi Arabia, who has shaken the kingdom by, among other things, arresting some important Saudi princes in a supposed crackdown on corruption. The new Jean Nouvel–designed Louvre Museum in Abu Dhabi announced that Salvator Mundi will be displayed in the near future, which will certainly bring in the crowds.

While this “masterpiece” will undoubtedly be dubbed the “Mona Lisa of the Middle East,” that title will always be clouded by the doubts raised by its style and murky history.