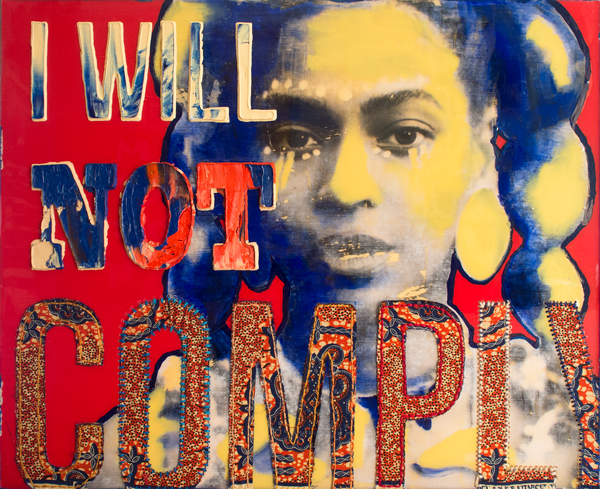

Los Angeles–based artist April Bey fuses her fine arts education with a background in design to create rule-based hybrid works that intertwine a host of materials such as caulking, resin and wood along with low quality sewing needles, thread and Hitarget wax fabric, produced in China and specifically marketed to impoverished black women. In her new series, “Afrofuturist Womanism,” Bey gives us an inspiring sense of hope by disclosing how our present-day technologies can in fact impart change for women of color in the here and now. We recently met to discuss her new work at her home/studio.

What was the catalyst that set this series in motion?

I’m interested in black women and entrepreneurialism, in particular social media entrepreneurialism. There are so many identities within blackness, but we haven’t seen a lot of nerdy women who are into sci-fi (a.k.a. blerds). More and more, they’re finding an audience though social media since the platform itself enables connectivity across the globe. Take Issa Rae, who first attracted attention from her YouTube web series Awkward Black Girl. That’s what intrigues me: how these women are using social media to build businesses.

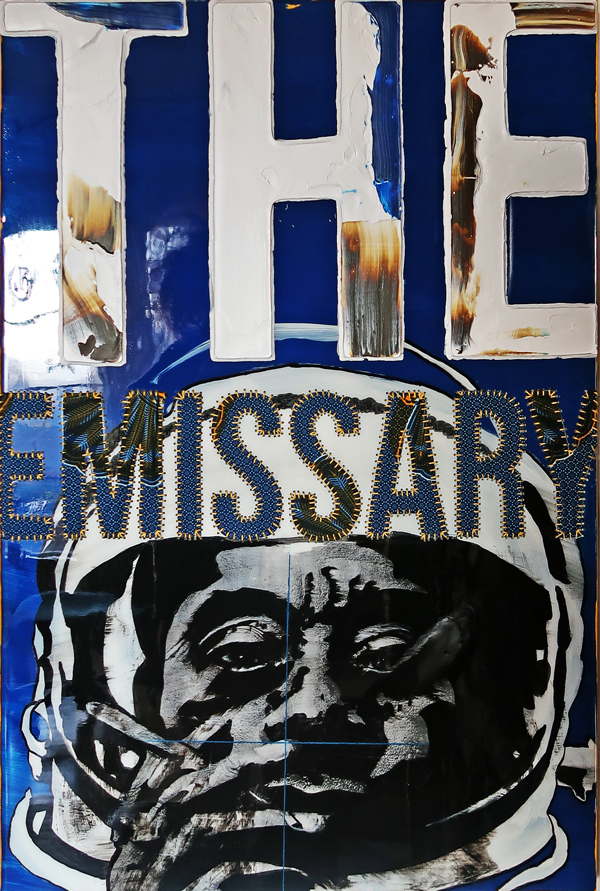

The Emissary, 2018, oil paint, Ghanaian/Chinese Hitarget Wax fabric, hand sewn into wood panel with epoxy resin, 30×24 in.

In your words, can you explain Afrofuturism?

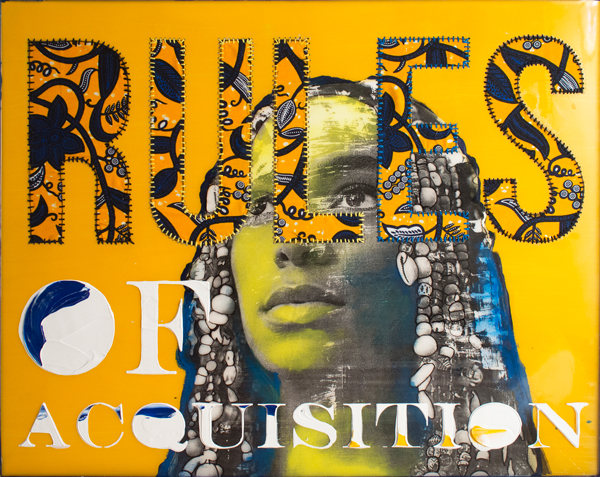

Imagine growing up in a world where anyone could play any role, where race didn’t mean anything, a place where the president could be black and it wouldn’t be a historical event. That’s what Afrofuturism is to me. We’ve seen this concept played out in Star Trek for years. As long as the crew remained in space, race was never an issue, which is why I’ve incorporated Star Trekian texts into almost all of my paintings for this series.

Can you explain the context behind the pairing of text with each of your subjects?

I grew up in the Caribbean, so I didn’t understand much about African American culture, other than what I’d seen in the media and had tried to emulate on the Island. When I moved to Indiana to finish school, I was surrounded by a lot of people who tokenized me. Because I was black, they expected me to be ghetto or into rap when in fact I was reading Harry Potter and World War II memoirs.

By the Grace of The Grand Nagus, 2018, Ghanaian Hitarget Chinese fabric sewn into resin on panel, acrylic paint, 30 x 24 in

I was different, like the individuals I depict in this series. Take Grace Jones and James Baldwin, whom I juxtapose against one another. Both were so fluid in regards to gender representation and sexual orientation, which has always been a contentious issue in the African American community. Jones’ Jamaican heritage forced her to reconcile with her identity while Baldwin left the country to write about what it’s like to be a queer black man. Although both were seen as outsiders in the U.S, they remain revered for their strengths, which is why I gave each a title of authority to accompany their portraits. Grand Nagus, for example, was the leader of the Ferengi Alliance on Deep Space Nine, while The Emissary was Captain Sisko’s title, the first black captain to appear on the show.

RULES (Ferengi Feminism), 2017, oil, acrylic, epoxy resin and hand sewn Ghanaian Hitarget Chinese fabric, 24×30 in.

Beyoncé and Solange appear in this series. Why did you choose these two figures?

Beyoncé is radical and heavy-handed in her visuals whereas Solange is softer and nomadic. Solange is the type of artist who goes off and lives in Nigeria for a month to work on her art whereas Beyoncé can be very corporate and entertainment-focused. While they both provide therapeutic value for black women, Beyoncé causes the oppressor to be uneasy and spits in your face whereas Solange is much more subtle and promotes self-care. The series also includes portraits of Michaela Coel from Chewing Gum; Tracy Ann (Tap), a social media figure in The Bahamas; Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, author of Americanah and whom Beyoncé sampled on her album before Lemonade; and Issa Rae, creator and star of HBO’s Insecure.

Although you don’t consider yourself an Afrofuturist, what does the allusion to that aesthetic offer your audience?

Afrofuturism spans beyond any definable protocol, so it offers unlimited possibility. Some of the figures in my work utilize this aesthetic of maneuverability to bend and stretch the labels we’ve adhered to for so long, labels associated with sexual orientation, gender representation, race, ethnicity, nationalism and so on.

Like any Afrofuturist, I’m interested in the depiction of what could be rather than what is. I think where I deviate is in showing how prevalent technologies and creations can influence this future version of us. I focus on social media because it’s a tool my generation has used and is still using to occupy space—albeit virtual space—and create physical spaces for opportunities. I can be patient and wait for a future devoid of racism and hierarchies based on class, but I’m also capable of seeing current trends and instruments available now to accelerate the progress.

All images courtesy of the artist.

Catch April Bey at our upcoming panel discussion on Identity Art at Bermudez Projects, May 12. For more info click here.