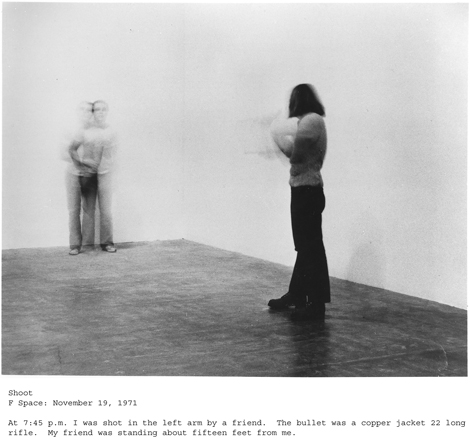

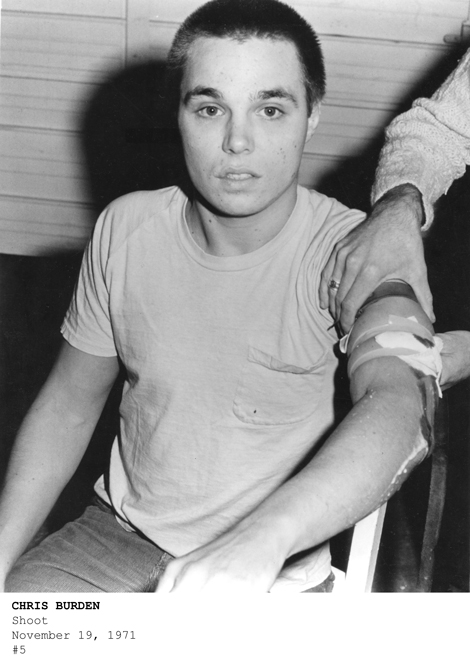

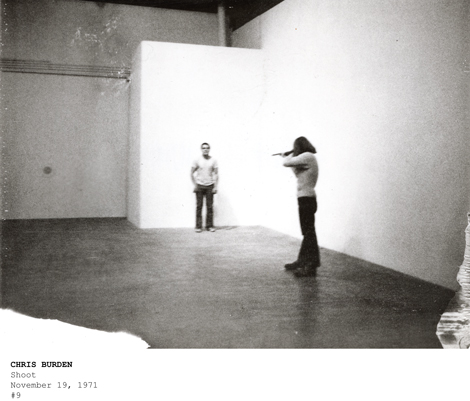

Nearly all of Chris Burden’s numerous and generally laudatory obituaries include in the title or first line, “…the artist who had himself shot.” Beyond the immediate and not so subtle insinuation of craziness—“People thought he was nuts,” an admiring Ed Moses told the LA Times—lies an acknowledgement of the power of Shoot. Performed 44 years ago, for only a handful of invited viewers, Shoot employed a marksman-friend who shot Burden in the left arm with a rifle. The formerly anonymous shooter was recently identified as Bruce Dunlap by an opinion piece in The New York Times, which elicited vitriolic condemnations of the performance in the vast majority of readers’ comments. While mean-spirited and reprehensible, the inflammatory tone of the letters-to-the-editor should not be surprising. Shoot continues to viscerally shock and vividly resonate even today, like the very best avant-garde art. The point of the 19th-century artistic creed, épater le bourgeoisie (amaze the middle classes!), was to keep culture moving, to prevent it from lapsing into a frozen status quo. In Clement Greenberg’s definitive analysis of 1939, the avant-garde—the Hegelian antithesis to the bourgeois thesis—was propelled forward by its opposition to static conservatism. Burden is the last of the avant-garde’s great practitioners, as I and others have long maintained. In the same way that Jackson Pollock, according to Allan Kaprow, “destroyed painting,” Burden killed off the avant-garde, taking it to unsurpassable limits.

Naïve he was not, nor oblivious to the public awareness and longevity of Shoot. In 1978, he said of its impact: “Take my getting shot in the arm, which is the big piece I’m famous for. I was able to do a piece of sculpture that didn’t take any material except a rifle, that was over in a split second and that basically existed by word of mouth. And that’s, I think, what attracted me—not getting shot particularly, but the whole conciseness of the thing. In essence that’s giving the shaft to MGM, with their fancy sets and million-dollar budgets. Phillip [sic] trotted across the room and shot me in the arm for one millisecond: big deal. But in terms of the media—and that includes word of mouth—it worked.”

The typical reaction by conservatives—who live up to the label by seeking to conserve the status quo—is the diagnosis of insanity, closely followed by those who refuse to accept Burden’s performance work as art. The latter denunciation is usually issued by art-world outsiders. In our YouTube-saturated era, a less common but more justifiable response to Shoot is shock. Following a recent classroom screening of Burden’s 1974 film documenting his performance work, including Shoot, a distraught student reported me to the university’s top administrative officials, claiming that she and her classmates were unprepared for what she considered the violence and pornography of his work. (They must have missed the hour-long lecture I’d given on Burden in the previous class.) Their collective shock, exclusive of the subsequent tattling, was the right response. Reinforcing my point that Burden’s art contributed to the end of the avant-garde is the fact that his post-performance work is as pleasing and well-liked as the earlier work is disliked by (non-art world) viewers.

While refusing even to classify Shoot as a work of art, based on its likability rather than the fact that it was made by an artist, presented in a gallery, and has become a “major monument” of art history, the same bourgeois crowd delights in the racing or traffic-jammed miniature cars of the enormously powerful Metropolis II at LACMA every weekend. Whether inspired by the televised violence of Vietnam and Kent State or the lemmings-like congestion of Los Angeles freeways, Burden’s work reflects the everyday lives of Americans, like it or not. The resilience and provocation of his work, the repulsion or magnetism it continues to exert on the public as well as seasoned viewers and New York art critics—who also too frequently dismissed him—are proof of his real greatness as an artist.